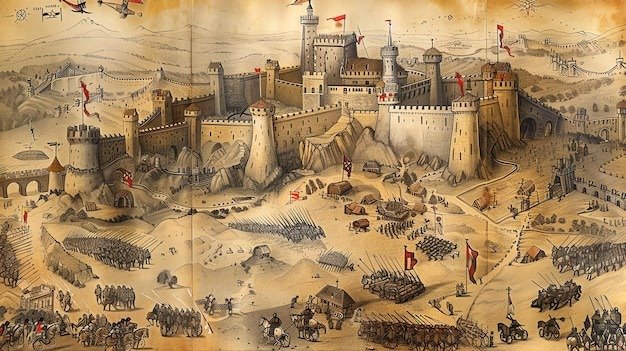

Long before modern weapons, standing armies, or national borders, human survival depended on one hard truth: whoever could defend a fixed place could shape the future. Ancient fortresses were not romantic ruins or symbols of glory. They were life-support systems built in stone, earth, and wood, designed to withstand violence, hunger, fear, and time itself. Every wall, gate, and tower was the result of accumulated experience—lessons learned from failed defenses, lost cities, and entire populations wiped out.

These structures were not built merely to repel attackers. They protected food reserves that sustained societies through winter and drought, water systems that determined whether a city lived or died, religious centers that legitimized authority, and political institutions that kept order in fragile worlds. A fortress was an economic engine, a psychological weapon, and a social contract all at once. To live within its walls was to accept protection in exchange for obligation.

Ancient defensive systems evolved through centuries of trial and catastrophe. Builders adapted to geography, climate, available materials, and the changing nature of warfare. Siege tactics grew more sophisticated, and so did countermeasures. What emerged was not a single idea of defense, but a network of principles—layered protection, controlled access, endurance under isolation, and the manipulation of time as a weapon.

This article examines ancient fortresses as functional systems rather than static monuments. It looks at how they were planned, built, supplied, attacked, defended, and ultimately abandoned. More importantly, it explores what these defensive structures reveal about the societies that created them—how they understood power, fear, cooperation, and survival.

1. Why Defense Became Central to Civilization Itself

Defense became essential the moment humans shifted from mobile survival to permanent settlement. Early villages could scatter when threatened, but cities could not. Once grain was stored in bulk, once temples anchored belief systems, once rulers governed from fixed locations, loss was no longer temporary. A single successful raid could erase years of labor.

As societies grew more complex, so did their vulnerabilities. Agriculture created surplus, surplus created inequality, and inequality created conflict. Fortresses were built to protect not just people, but structure itself: economic systems, religious authority, and political legitimacy. In many ancient cultures, the city wall marked the boundary of law. Inside the walls, rules applied. Outside, chaos ruled.

Defense also shaped identity. People did not simply live in a city; they lived within its walls. Belonging was physical. Citizenship, protection, and obligation were tied to the fortress. When walls expanded, power expanded. When they fell, identity fractured.

Importantly, fortresses allowed civilizations to think long-term. Without reliable defense, no society could invest in art, science, or administration. Walls bought time. Time created culture.

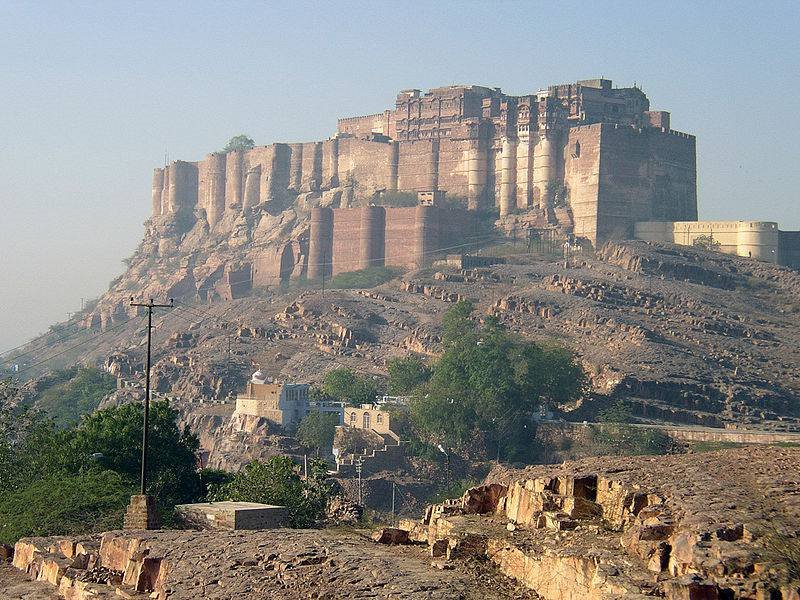

2. Choosing the Ground: Geography as the First Weapon

Ancient builders understood that the strongest wall meant little if placed poorly. Geography was the first and most powerful layer of defense, often more decisive than stone or soldiers.

High ground offered several advantages at once. Attackers approaching uphill lost momentum, formation, and stamina. Defenders gained visibility, range, and psychological dominance. Even poorly armed defenders could repel stronger forces simply through position.

Water was equally critical. Rivers, marshes, lakes, and coastlines acted as natural barriers that slowed armies and disrupted supply lines. Many ancient cities were built where rivers bent sharply, creating protected flanks while allowing trade access. In flood-prone regions, seasonal waters became defensive tools, isolating cities at key times of year.

Climate also mattered. Desert fortresses exploited heat, lack of water, and long supply routes to weaken enemies before combat even began. Mountain fortresses relied on thin air, narrow passes, and unpredictable weather. Dense forests concealed movement while limiting large formations.

Choosing a site was a strategic decision with consequences lasting centuries. A well-chosen location could compensate for weaker walls; a poor one could doom even the strongest fortress.

3. Walls Were Systems, Not Barriers

To modern eyes, ancient walls look static and simple. In reality, they were dynamic systems designed to absorb, redirect, and survive prolonged violence.

Most effective walls were composite structures. Instead of solid stone, they often used layered construction: stone or brick outer faces filled with rubble, earth, or sand. This absorbed shock from rams and projectiles better than solid masonry, which could crack catastrophically.

Thickness mattered more than height. Many walls were wide enough to support buildings, storage rooms, and troop movement on top. Some contained internal chambers used for supplies or shelter during bombardment.

Wall angles were carefully calculated. Slight slopes reduced climbing effectiveness and deflected falling objects. Rounded corners resisted impact better than sharp edges. Parapets protected defenders while allowing visibility and fire.

Maintenance was constant. Walls required drainage to prevent water damage, regular resurfacing, and structural reinforcement. A neglected wall was a weak wall, no matter how impressive it once looked.

In essence, walls were not meant to be invincible. They were meant to slow, tire, and frustrate attackers long enough for defense to succeed.

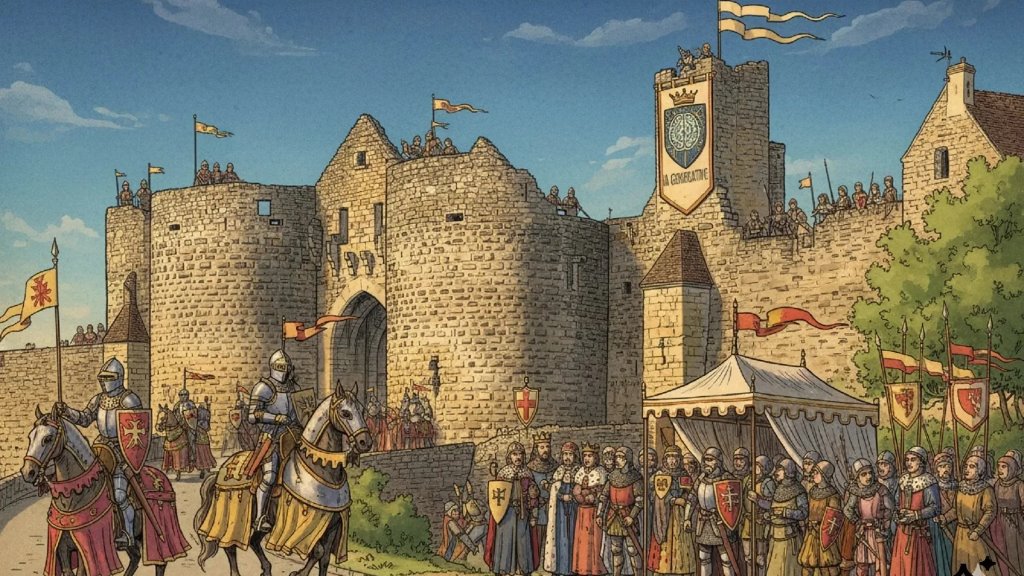

4. Gates: Where Engineering and Psychology Met

Gates were paradoxes. They were essential for trade, communication, and daily life, yet they represented the greatest vulnerability in any defensive system. Ancient engineers responded by turning gates into controlled environments rather than simple openings.

Instead of straight passages, many gates used angled or zigzag designs that forced attackers to slow down, turn, and break formation. This exposed their unshielded sides and made coordinated assault difficult.

Multiple doors were common. Heavy wooden gates reinforced with metal were followed by inner doors, portcullises, or secondary barriers. Attackers who breached one door often found themselves trapped between layers under concentrated fire.

Gatehouses were heavily fortified structures in their own right. Towers flanking entrances allowed defenders to attack from above and the sides. Narrow ceilings enabled stone drops, boiling liquids, or spears.

Beyond physical defense, gates carried psychological weight. They were ceremonial symbols of power, often decorated to intimidate visitors and remind enemies of authority. To approach a gate was to confront the identity of the city itself.

5. Towers, Height, and Control of Space

Towers transformed static walls into active defensive platforms. Their value extended far beyond simple height.

From towers, defenders could observe enemy movements hours or days in advance. Early warning meant preparation, reinforcement, and sometimes evacuation. In large defensive networks, towers communicated using smoke, fire, mirrors, or flags, transmitting information across vast distances.

In combat, towers allowed flanking fire along the wall face, targeting attackers attempting to climb or undermine defenses. Even simple projectiles gained deadly effectiveness when dropped from height.

Towers also served as command centers. Officers could coordinate defense, direct troop movement, and monitor multiple sectors at once. Losing a tower often meant losing control of that section of the wall.

Psychologically, towers projected dominance. A skyline lined with towers told attackers they were being watched, measured, and anticipated. Many sieges ended before they began simply because towers made resistance feel inevitable.

6. Water, Food, and the Reality of Siege Survival

In ancient warfare, the most effective weapon was often time. A fortress that could survive without outside help turned every siege into a test of endurance—and endurance depended almost entirely on logistics. Water, food, sanitation, and internal organization mattered more than walls once the enemy settled in.

Water was the single most critical factor. Ancient fortress builders went to extraordinary lengths to secure it. In rocky regions, cisterns were carved directly into bedrock and plastered to prevent leakage. Rainwater was guided through channels from rooftops and courtyards into underground reservoirs. Some cities protected natural springs with stone shafts hidden inside the walls, making them unreachable to attackers.

Food storage was equally calculated. Grain was favored because it could last years if kept dry and protected from pests. Archaeological finds show sealed storage jars, elevated platforms, and even temperature-controlled chambers. Some fortresses stored food not just for soldiers, but for entire populations, including animals essential for transport and agriculture after the siege ended.

Sanitation was a silent but deadly concern. Waste disposal systems, drainage channels, and designated dumping zones were critical. Disease could collapse a fortress faster than hunger. Successful defenses relied on strict internal discipline, ration control, and social order. Chaos inside the walls was more dangerous than any enemy outside.

7. Siege Warfare: How Attackers Actually Tried to Break Fortresses

Ancient sieges were rarely dramatic assaults with ladders and shouting armies. Most were slow, methodical, and brutally pragmatic. Attackers aimed to break the fortress without destroying what they wanted to capture.

The most common tactic was blockade. Armies surrounded a city, cut supply lines, poisoned nearby wells, and waited. This required patience, resources, and discipline—qualities not all armies possessed. Many sieges failed simply because attackers could not sustain themselves long enough.

When active measures were used, they included battering rams protected by wooden sheds, siege towers rolled toward walls, and tunneling beneath foundations. Fire was a constant threat, especially against wooden gates and internal structures.

Psychological warfare played a major role. Attackers displayed prisoners, executed captives in view of defenders, spread rumors, or attempted bribery. The goal was to create doubt and division inside the walls. A fortress rarely fell from the outside alone.

8. Defensive Countermeasures and Fortress Adaptability

Defenders were not passive victims of siege tactics. Ancient fortresses were designed with adaptability in mind, allowing defenders to respond creatively under pressure.

Against tunneling, defenders dug counter-tunnels, listening for vibrations through the ground. When tunnels met, underground combat occurred in darkness and confined spaces. In some cases, defenders collapsed tunnels intentionally, burying attackers alive.

Walls were repaired during sieges. Stones were stockpiled specifically for this purpose. Temporary wooden structures reinforced damaged sections. Fires were extinguished with sand, water, or vinegar-soaked cloths.

Defenders also launched surprise sorties—short attacks against siege camps to burn equipment, disrupt morale, or capture supplies. These raids were risky but effective in prolonging defense.

The most successful fortresses treated defense as an ongoing process, not a fixed plan. Flexibility often determined survival.

9. Regional Fortress Design and Environmental Adaptation

No two regions built fortresses the same way, because threats were never the same.

In deserts, fortresses focused on water control rather than massive walls. Narrow access routes, camouflage, and heat exhaustion did much of the defensive work. In river valleys, walls were thicker and cities larger, reflecting higher population density and greater economic value.

Mountain fortresses emphasized narrow passes and verticality. Attackers could only approach in small numbers, making large armies ineffective. Coastal fortresses integrated naval defenses, controlling harbors with chains, towers, and sea walls.

Materials shaped design. Where stone was scarce, mudbrick was perfected. Where timber was abundant, wooden palisades and earthworks dominated. These were not inferior solutions, but optimized ones.

Every fortress was a response to its environment, not a universal blueprint.

10. Defensive Networks Beyond Cities

Some defensive systems extended far beyond individual fortresses. Empires learned that controlling space mattered more than defending points.

Long walls, frontier forts, and watchtower chains created early warning systems. These networks delayed invasions, guided troop movement, and protected trade routes. They were less about stopping enemies entirely and more about managing pressure and buying time.

Communication was key. Signals passed rapidly across distances allowed centralized responses to local threats. This turned defense into a coordinated system rather than isolated strongholds.

Such networks also served political purposes. They defined borders, projected authority, and reminded populations where imperial power began and ended.

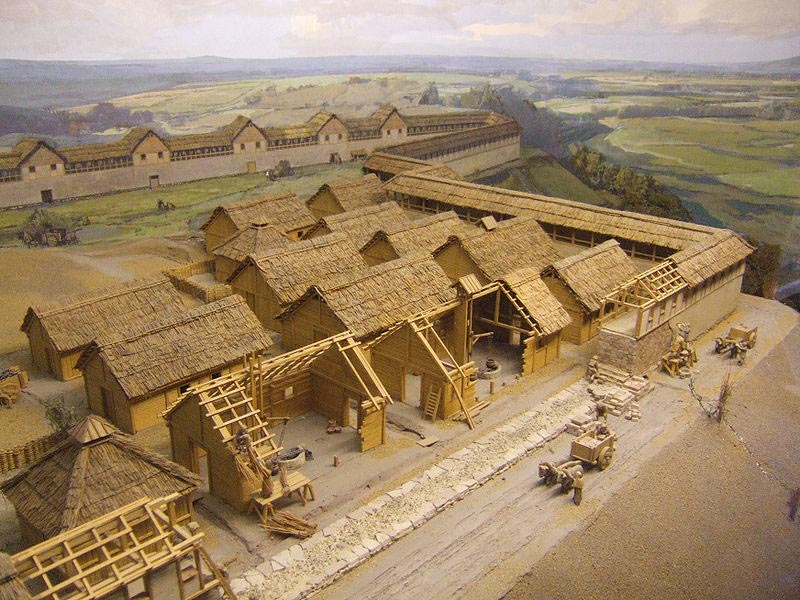

11. Life Inside Fortress Walls During Peace and War

Fortresses were not permanent states of emergency. Most of the time, they functioned as ordinary urban environments with extraordinary readiness.

People lived, worked, worshipped, and raised families within walls. Workshops produced weapons, tools, and everyday goods. Markets operated under the protection of towers and gates.

During sieges, daily life became rigidly controlled. Food was rationed, movement restricted, and labor assigned. Civilians often assisted in repairs, supply management, and lookout duties. Defense was a collective effort, not a purely military one.

Psychological strain was immense. Long sieges produced fear, despair, and conflict within communities. Maintaining morale was as important as maintaining walls.

12. Why Fortresses Ultimately Fell

Despite their sophistication, most ancient fortresses eventually fell—not because of failed engineering, but because of human limits.

Betrayal opened gates more often than battering rams. Starvation eroded loyalty. Political collapse left defenders unpaid and unsupported. Disease ignored walls entirely.

When central authority weakened, fortresses became liabilities instead of assets. Maintenance stopped. Garrisons shrank. Walls crumbled not from attack, but neglect.

A fortress could survive assault, but it could not survive a broken society.

13. The Enduring Legacy of Ancient Defensive Systems

Modern defense still follows ancient logic. Layered security, controlled access, redundancy, early warning, and psychological deterrence all trace back to ancient fortresses.

Even beyond warfare, these principles shape urban planning, architecture, and digital security. Firewalls, checkpoints, and surveillance networks are conceptual descendants of walls and towers.

Ancient fortresses remind us that security is never absolute. It is a balance between strength, adaptability, and social cohesion. Stone may crumble, but the thinking behind it continues to shape how humans protect what they value most.

Deep Engineering Reality Behind Ancient Fortress Construction

Ancient fortresses were massive engineering projects that pushed the limits of pre-industrial technology. Construction often lasted decades and required centralized authority, forced labor, skilled artisans, and long-term resource planning. Stones weighing several tons were quarried, transported, shaped, and placed without modern machinery. In some regions, ramps of packed earth were built just to move blocks upward, then dismantled once construction ended.

Foundations were critical. Builders understood soil behavior even without modern geology. In floodplains, walls sat on layers of gravel and compacted earth to prevent sinking. In seismic zones, stones were fitted with slight flexibility, allowing walls to absorb shock instead of cracking. Mortar was not always used; in many cases, precision-cut stone held better over centuries than bonded masonry.

Wood played a hidden role. Timber beams were embedded inside walls to distribute stress. In colder regions, wood also acted as insulation, reducing freeze damage. Where timber was scarce, reeds, clay, or even animal hair were mixed into construction material to increase durability.

This level of planning shows that ancient fortresses were not crude defenses. They were calculated machines built to endure both war and time.

Siege Duration, Attrition, and the Mathematics of Starvation

Most popular depictions of sieges focus on combat, but real sieges were logistical equations. Attackers calculated food consumption, disease risk, troop morale, and political pressure back home. Defenders calculated how long supplies would last under rationing.

Records and archaeology suggest that well-prepared fortresses could survive:

-

6 to 12 months under strict rationing

-

2–3 years in exceptional cases

-

Sometimes longer if external relief arrived

Grain consumption was carefully measured. Bread was often mixed with fillers such as legumes or ground roots to extend supplies. Animals were slaughtered in stages to preserve fresh meat longer. Water use was restricted to survival needs only.

Attackers often suffered more than defenders. Camps outside walls were exposed to weather, poor sanitation, and limited water. Disease spread rapidly in siege armies. Many sieges ended because attackers withdrew—not because defenders surrendered.

Time was the fortress’s strongest weapon.

Psychological Warfare Inside the Walls

Life during a siege was mentally destructive. Even when food and water remained, fear could tear a fortress apart.

Ancient commanders understood this and used ritual, religion, and symbolism to stabilize morale. Public prayers, sacrifices, and ceremonies reassured populations that defense had divine support. Leaders made visible appearances on walls to project confidence, even when situations were desperate.

Control of information was vital. News of defeats elsewhere was suppressed. Rumors were punished harshly. In many cases, internal dissent was treated as treason because morale collapse could be fatal.

Children and non-combatants were not sheltered from reality. Archaeology shows signs of malnutrition, stress fractures, and hastily buried bodies inside fortresses, indicating prolonged psychological strain.

Walls could hold bodies. Minds were harder to defend.

When Fortresses Became Tools of Control, Not Protection

As states centralized, fortresses increasingly served rulers more than populations.

In some cities, internal citadels were built inside outer walls. These inner fortresses protected elites from both external enemies and internal rebellion. Food storage and water access were often controlled from these inner strongholds, ensuring loyalty through dependence.

Garrisons sometimes enforced taxation, conscription, and labor obligations. Movement through gates was regulated. Walls that once symbolized collective survival began to symbolize authority and coercion.

This shift explains why some populations did not defend fortresses fiercely when attacked. A wall that protects oppression is rarely defended with the same commitment as one that protects community.

Why Gunpowder Didn’t Instantly End Fortresses

It is often said that cannons made fortresses obsolete. This is only partly true.

Early gunpowder artillery was slow, inaccurate, and resource-intensive. Many ancient-style walls survived early cannons by adapting:

-

Walls became lower but thicker

-

Earth was packed behind stone to absorb impact

-

Angled bastions reduced direct hits

These transitional fortresses show continuity rather than sudden collapse. What truly ended ancient defensive systems was not firepower alone, but economic and political change. Standing armies, centralized taxation, and mobile warfare reduced the strategic value of fixed defenses.

Fortresses didn’t fail technologically first. They failed systemically.

What Ancient Fortresses Ultimately Teach Us

Ancient defensive systems reveal a fundamental truth: security is not a structure, it is a process.

Walls worked when:

-

Society was cohesive

-

Leadership was legitimate

-

Resources were managed rationally

-

Defense was shared, not imposed

They failed when:

-

Internal trust collapsed

-

Logistics broke down

-

Authority lost credibility

-

Adaptation stopped

This lesson extends beyond warfare. Modern states, cities, and even digital systems face the same reality. Strong defenses mean nothing without internal stability.

Ancient fortresses were humanity’s first large-scale attempt to make permanence possible in a hostile world. They succeeded often enough to shape civilization—but never permanently enough to stop history from moving forward.

Stone held the line for centuries. Human weakness always decided the end.