Genghis Khan was a powerful warrior and political leader who lived during the early thirteenth century in Central Asia and went on to establish the Mongol Empire, one of the most expansive empires the world has ever known. By the time of his death, the empire stretched across vast regions of China and Central Asia, with Mongol armies pushing westward as far as Kiev in present-day Ukraine. What began as a collection of fragmented nomadic tribes eventually transformed into a unified force that reshaped the political, military, and economic landscape of Eurasia. After Genghis Khan’s death, his successors continued his campaigns, ruling over territories that extended into the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe.

Who was Genghis Khan?

Born under the name Temujin in Mongolia around the early 1160s, Genghis Khan rose from a childhood marked by instability and hardship to become the architect of a global empire. He married at a young age, following Mongol customs, and later took multiple wives, a common practice among steppe elites of the time. In his early adulthood, Temujin began assembling a loyal military force with a clear objective: to eliminate the entrenched rivalries among Mongol and neighboring tribes and bring them under centralized leadership. Through relentless campaigns and strategic alliances, he succeeded. The Mongol Empire eventually surpassed all previous empires in territorial continuity, predating even the British Empire in scale. Remarkably, it endured long after Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, continuing to influence world history for generations.

Despite his historical importance and fearsome reputation, many details about Genghis Khan’s life remain uncertain. No verified portrait of him exists today. According to Jean-Paul Raux, professor emeritus at the École du Louvre, all surviving images of Genghis Khan were created after his death or by individuals who never saw him in person. As a result, modern depictions are shaped more by legend, symbolism, and later interpretation than by direct observation.

Another challenge in understanding his life lies in the absence of early Mongolian written records. Prior to Genghis Khan’s rise to power and his incorporation of the Uyghur people, the Mongols did not possess a formal writing system. Many surviving accounts were therefore recorded by foreign observers, often enemies or distant chroniclers. One of the most important native sources, The Secret History of the Mongols, was written anonymously sometime after his death and blends historical detail with oral tradition, making precise facts difficult to confirm.

Based on available evidence, historians generally agree that Genghis Khan was born around AD 1160, though the exact year is unknown. He died in August 1227, reportedly from natural causes, while conducting a punitive military campaign against the Tangut people. After his death, the Tangut population suffered devastating reprisals, underscoring the ruthless efficiency with which Mongol succession plans were enforced.

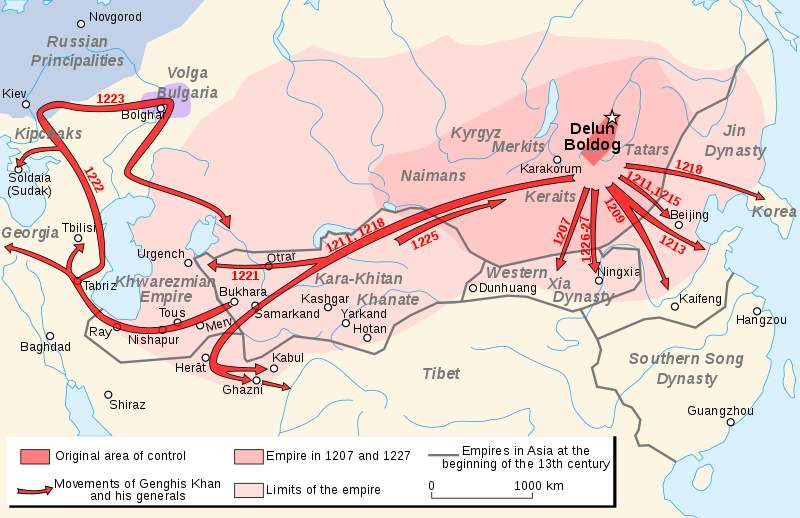

Significant conquests and movements of Genghis Khan and his generals

Early Years and Tribal Origins

Born in north-central Mongolia, Temujin was named after a defeated Tatar chieftain captured by his father, Yesukhei. He belonged to the Borjigin clan and traced his lineage to Khabul Khan, an earlier Mongol leader who had briefly united tribes against the Jin Dynasty of northern China. According to The Secret History of the Mongols, Temujin entered the world clutching a blood clot in his hand, an omen in Mongol folklore believed to signify future leadership and power. His mother, Hoelun, played a crucial role in shaping his character, teaching him resilience, survival, and the importance of forming alliances in a volatile tribal environment.

At the age of nine, Temujin was sent to live with the family of his future wife, Borte, in keeping with Mongol customs intended to strengthen intertribal bonds. While returning home from this arrangement, his father accepted an invitation to dine with members of the rival Tatar tribe. The meal proved fatal, as Yesukhei was poisoned in retaliation for past conflicts. Temujin returned home only to discover that his family had been abandoned by their clan, which refused to accept a child as leader. Reduced to poverty and isolation, Temujin’s family survived on wild foods and constant vigilance.

The pressure of survival led to internal conflict. During a dispute over hunting spoils, Temujin killed his half-brother Bekhter, a decisive and violent act that secured his authority within the household. Though grim, this moment marked his emergence as a figure willing to act decisively to maintain control.

At sixteen, Temujin married Borte, solidifying an alliance with the Konkirat tribe. Shortly afterward, Borte was abducted by the Merkit tribe and given to one of their leaders. Temujin sought help from allies and successfully rescued her. Soon after her return, she gave birth to their first son, Jochi. Although doubts lingered regarding Jochi’s paternity, Temujin openly accepted him, a choice that would later influence succession politics. Together, Temujin and Borte had four sons, while additional children were born to other wives. According to tradition, however, only Borte’s sons were considered legitimate heirs.

Rise of the Universal Ruler

In his early twenties, Temujin was captured during a raid by the Taichi’ut tribe, former allies turned rivals. He was enslaved and restrained with a wooden collar, but managed to escape with the help of a sympathetic guard. Reuniting with his brothers and loyal followers, Temujin began to organize a disciplined fighting force. Instead of relying solely on blood ties, he promoted loyalty based on merit, a revolutionary idea in steppe society.

Over time, his army grew to tens of thousands of warriors. He deliberately dismantled traditional tribal divisions, restructuring his forces to weaken old rivalries and reinforce allegiance to himself alone. Using swift cavalry maneuvers, psychological warfare, and strict discipline, Temujin defeated one rival tribe after another. He annihilated the Tatars in vengeance for his father’s death, ordering the execution of adult males beyond a certain height. The Taichi’ut leadership was destroyed in brutal fashion, and the powerful Naiman tribe soon followed.

By 1206, Temujin controlled most of central and eastern Mongolia. Tribal leaders convened and formally granted him the title Genghis Khan, meaning “Universal Ruler.” This title carried religious as well as political meaning. Mongol shamans proclaimed him the chosen representative of the Eternal Blue Sky, the supreme spiritual force in Mongol belief. From that moment, obedience to Genghis Khan was equated with obedience to divine will, reinforcing his authority across the steppe.

The Mongol military machine was highly advanced for its time. Soldiers were expertly trained horsemen capable of firing arrows at full gallop. Each carried multiple weapons, supplies, and waterproof saddlebags that could double as flotation devices. Communication relied on smoke signals, drums, and flags, allowing large forces to coordinate complex maneuvers. An organized logistical network followed the army, ensuring food, equipment, spiritual support, and systematic recording of captured wealth.

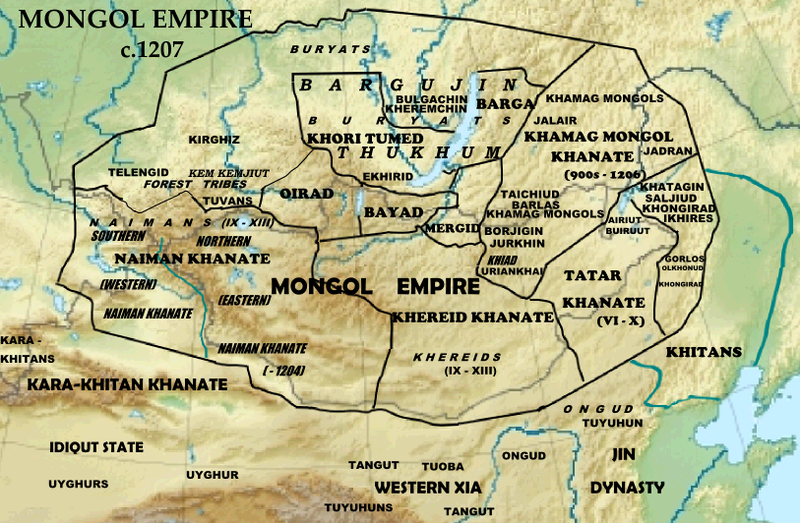

Mongol Empire c. 1207

Expansion and Imperial Campaigns

Empowered by both spiritual authority and practical necessity, Genghis Khan launched a series of campaigns that rapidly expanded Mongol territory. Environmental pressures, including population growth and limited grazing land, likely intensified the need for conquest. In 1207, Mongol forces attacked the kingdom of Xi Xia, eventually forcing its submission after sustained pressure. Soon after, in 1211, Mongol armies invaded the Jin Dynasty of northern China, targeting fertile agricultural regions and wealth rather than cultural centers.

While fighting in the east, Genghis Khan initially pursued diplomacy in the west. He sought trade relations with the Khwarizm Dynasty, which controlled vast territories across Central Asia and Persia. These efforts collapsed when Mongol envoys were murdered by the governor of Otrar. The Khwarizm ruler compounded the insult by executing a Mongol diplomat and returning his severed head. This act triggered one of the most devastating campaigns in medieval history.

In 1219, Genghis Khan personally orchestrated a massive, multi-directional invasion involving roughly 200,000 troops. City after city fell. Resistance was met with overwhelming force, and survivors were often used as human shields. Entire populations were wiped out, livestock destroyed, and urban centers reduced to ruins. By 1221, the Khwarizm Dynasty was eliminated, its rulers hunted down and killed.

Following these conquests, a period often described as the Pax Mongolica emerged. Trade routes linking East Asia and Europe were secured, facilitating commerce and cultural exchange. Governance across the empire was regulated by a legal code known as Yassa. This code outlawed practices such as theft, false testimony, and blood feuds, while also mandating environmental protections and military discipline. Advancement within the empire depended on ability rather than ancestry, and religious tolerance was largely maintained, reflecting pragmatic governance across a culturally diverse population.

Genghis Khan later returned his attention to Xi Xia, whose leaders had refused to support earlier campaigns. After defeating Tangut forces and capturing their capital, he ordered the execution of the imperial family, bringing the Tangut state to an end.

Death and Lasting Legacy

Genghis Khan died in 1227 shortly after the final submission of Xi Xia. The circumstances of his death remain unclear, with theories ranging from injuries sustained in a fall to illness. In accordance with Mongol tradition, he was buried in an unmarked grave near his birthplace, likely close to the Onon River and the Khentii Mountains. Legends claim that his funeral procession killed all witnesses and altered the landscape to conceal the burial site forever.

Before his death, Genghis Khan designated his son Ogedei as supreme ruler. The empire was divided among his other sons, each governing different regions. Expansion continued under Ogedei’s leadership, reaching its greatest extent as Mongol armies advanced into Persia, southern China, and Eastern Europe. The westward advance halted only after Ogedei’s death, when commanders were recalled to Mongolia to address succession matters.

Among Genghis Khan’s many descendants, Kublai Khan emerged as one of the most influential. A grandson through Tolui, Kublai embraced aspects of Chinese culture and governance, eventually founding the Yuan Dynasty. His rule marked a significant chapter in the fusion of Mongol and Chinese political traditions, extending the legacy of Genghis Khan far beyond the steppe and into the foundations of East Asian history.