World War One is the name most people use today, but it is worth asking whether that label truly fits the conflict that erupted in 1914. Was it genuinely a world war in scope, or was it primarily a European catastrophe with global side effects? And if it was global, can it really be described as the first war of its kind?

People living through the conflict certainly believed they were witnessing something unprecedented. The term “World War” first appeared in Germany in 1914, rendered as Weltkrieg, a word that conveyed the sense that the foundations of the world itself were giving way. In France and Britain, the conflict was initially known as La Grande Guerre or simply the Great War, but the idea of a world war gained traction as the fighting expanded and the costs became impossible to ignore.

For Germany in particular, the war felt global from the outset. Facing Britain and France, both of whom ruled vast overseas empires, German leaders and citizens perceived themselves as standing against an entire world system. The term “World War” was not just descriptive; it captured the psychological weight of a struggle that seemed to threaten the survival of civilisation itself.

After the end of the fighting in 1945, historians increasingly adopted the term “First World War” to distinguish the conflict of 1914–1918 from the even more devastating global war that followed two decades later. From this perspective, the earlier war became the first example of a new kind of conflict: an industrialised, total war involving mass armies, modern technology, civilian mobilisation, and economies redirected toward destruction on an unprecedented scale.

Yet this interpretation has always been open to challenge. Earlier conflicts such as the Seven Years’ War in the mid-18th century and the Napoleonic Wars at the turn of the 19th century were also fought across multiple continents and oceans. They disrupted global trade, involved rival empires, and drew in colonies from far beyond Europe. Compared with the Second World War, which saw vast campaigns across China, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific, the First World War can appear heavily centred on Europe, where the decisive land battles were fought.

The Seven Years’ War

The Seven Years’ War, fought between 1756 and 1763, involved all the major European powers of the time. France, Austria, Russia, and Sweden clashed with Britain, Prussia, and Hanover in a struggle that extended far beyond Europe. North America, India, the Caribbean, the Philippines, and large parts of central Europe were drawn into the conflict. For many historians, this war represents an earlier example of a truly global struggle, even if its scale and technology differed from those of the 20th century.

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars followed the upheaval of the French Revolution and raged from 1803 until Napoleon’s defeat in 1815. These campaigns pitted France against shifting coalitions of European powers and spread fighting across the continent and beyond. Conflict linked to the wars reached the United States, Latin America, Egypt, and Syria, demonstrating again that global warfare did not begin in 1914.

Despite these comparisons, the war that began in 1914 was undeniably global in its reach. The key difference lay in the automatic involvement of empires. When Britain, France, and Russia went to war, they brought with them colonial territories and dominions scattered across the world. British and French empires together spanned much of Africa, Australasia, and Asia. Russia’s land empire stretched from Eastern Europe through Siberia to the Pacific coast.

Japan entered the war on the Allied side in 1914, seizing German colonial possessions in China. The Ottoman Empire’s decision to join the conflict extended the fighting into the Middle East, from Iraq to Palestine. Later, the entry of the United States and Brazil, alongside Canada and Newfoundland as parts of the British Empire, ensured that nearly every continent was involved in some capacity.

Critics sometimes note that no major land battles were fought in the Americas, suggesting that this limits the war’s global character. Yet this view overlooks the significance of naval warfare. Engagements took place off the coasts of South America, including the battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands, and the war severely disrupted Atlantic shipping, directly affecting American trade and security.

The global nature of the conflict was evident from its very first shots. The opening engagement involving British forces occurred not in Europe, but in Africa, when Alhaji Grunshi, serving with British troops, fired upon German positions in Togoland. From that moment onward, the war unfolded across an astonishing range of landscapes.

The Western Front, running through Belgium and northern France, became the most famous theatre of the war. But much of Europe was transformed into a battlefield. The Eastern Front stretched from the Baltic Sea to the borders of Austria-Hungary, engulfing regions that are now Poland, Hungary, Romania, and the Baltic states. Serbia endured invasion and occupation, while Italy fought along its northeastern frontier and through the Dolomite mountains. Russia and the Ottoman Empire clashed across the rugged Caucasus.

As attempts to break stalemate intensified, the war expanded further. British forces opened new fronts at Gallipoli, in Mesopotamia, and in Palestine, capturing key cities such as Baghdad and Jerusalem. In the South Pacific, Australian troops seized German island colonies, including New Guinea. Japan captured the German port of Tsingtao in China. Across Africa, Allied forces fought to overrun Germany’s colonies in what are now Namibia, Tanzania, Cameroon, and Togo. Although not all of these campaigns lasted for the entire war, their geographical spread was extraordinary. Around two million Africans served as soldiers or labourers during the conflict.

Beyond the battlefields lay vast hinterlands where civilian life was shattered. Agricultural systems collapsed, trade routes were severed, and entire populations were displaced. In Africa, armies relied heavily on local porters, many of whom were coerced into service and suffered extreme hardship and high mortality. Eastern Europe experienced massive refugee movements, especially within the Russian Empire, a crisis deepened by revolution in 1917.

Minority populations often bore the brunt of wartime brutality. Jewish communities in Tsarist Russia faced persecution, while the Ottoman Empire carried out the systematic destruction of its Armenian population through mass deportation and massacre. These events underline how the war’s impact extended far beyond military engagements.

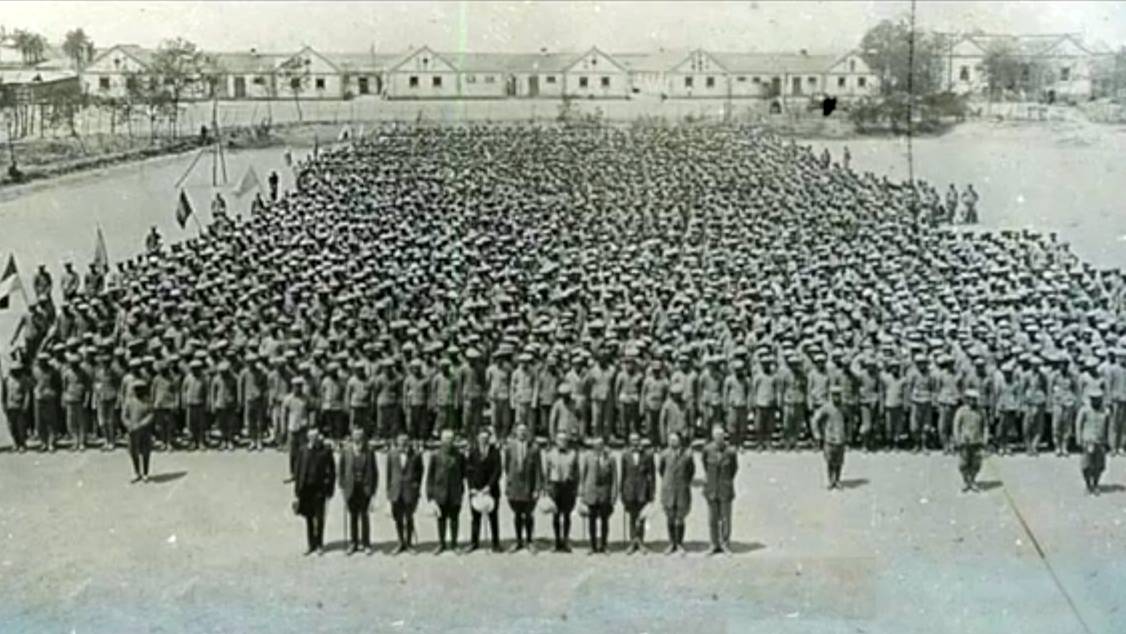

World War One was also global in the diversity of the people it mobilised. Britain recruited more than a million Indian soldiers, who fought on the Western Front, in East Africa, and in Mesopotamia. France drew troops from Indochina, Madagascar, Senegal, Algeria, and Tunisia. Germany used African colonial troops in its overseas territories, though it refused to deploy them in Europe, fearing a challenge to racial hierarchies.

Alongside soldiers, imperial powers recruited vast numbers of colonial labourers. Britain relied on workers from South Africa, Egypt, and the Caribbean, while Britain and France together transported around 135,000 Chinese labourers to Europe to support the war effort. These men often worked close to the front lines, exposed to danger and exploitation.

The war’s consequences were global in economic and ideological terms as well. Financial power shifted from London to New York during the conflict, reshaping the international economic order. With European agriculture devastated, countries such as Argentina and Canada emerged as major food suppliers.

Ideas also changed on a worldwide scale. Japan’s unsuccessful push for racial equality within the League of Nations signalled new challenges to established hierarchies. The first Pan-African Congress, held in Paris in 1919, called for African self-government. Across the world, the war stimulated debates about national self-determination and the need for international cooperation, embodied in the creation of the League of Nations.

Measured by its reach, its participants, and the transformations it unleashed, the war of 1914–1918 reshaped the global order in ways no previous conflict had done. In that sense, regardless of earlier precedents, it marked the first time the world was altered so completely by a single war.