For most of modern history, the world felt organized around a familiar structure. Power had a shape. You could point to capitals, alliances, institutions, and military blocs and roughly understand who mattered most and why. Even when tensions ran high, the rules of the game were mostly known. Today, that sense of clarity is disappearing.

The world order isn’t collapsing overnight, and it isn’t being replaced by a single new ruler either. What’s happening is slower, quieter, and in some ways more unsettling. Influence is spreading out, fragmenting, and reassembling in unexpected ways. Old assumptions about dominance, loyalty, and stability no longer hold up the way they once did. Countries that were once peripheral are gaining leverage, while traditional powers are finding their reach limited by internal pressures, technological disruption, and global fatigue.

This shift goes far beyond headlines about rival superpowers. It’s visible in trade routes being rerouted, supply chains being redesigned, alliances becoming more flexible, and economic tools replacing military force as the first line of pressure. Technology is reshaping power faster than armies ever could, while narratives and information have become weapons in their own right. Even geography feels different when data, capital, and influence move at digital speed.

What makes this moment especially complex is that no single factor explains it. Demographics, energy transitions, artificial intelligence, regional conflicts, financial systems, and public opinion are all pulling the global balance in different directions at once. The result is a world that feels less predictable, more competitive, and harder to control — especially for countries that once set the rules.

Understanding how global power is shifting isn’t just an academic exercise. It explains why wars look different, why economies feel more fragile, why diplomacy is more transactional, and why uncertainty has become a permanent feature of international life. This article explores the forces driving this transformation, how power is being redistributed, and what this changing world order really means beneath the surface.

The Slow End of a Single-Center World

For much of the late 20th century, global power had a clear center of gravity. After World War II, and especially after the Cold War, one country sat at the top of nearly every meaningful hierarchy: military reach, financial systems, cultural influence, and political institutions. Even nations that disagreed with its policies still operated inside structures shaped by it.

That era is fading, not because one rival suddenly overtook it, but because maintaining dominance has become harder in a world that is faster, more connected, and less forgiving of centralized control. Military superiority no longer guarantees political outcomes. Economic size doesn’t ensure supply-chain security. Cultural influence fractures across platforms and languages instead of flowing from a single source.

At the same time, internal pressures matter more than they used to. Aging populations, political polarization, rising debt, and public distrust limit how aggressively any power can project itself abroad. The result is not immediate decline, but reduced freedom of action. Power still exists, but it’s constrained, negotiated, and often reactive.

The Rise of Multipolar Influence

Instead of one clear leader, the world is drifting toward a multipolar system. Several countries now exert significant influence, each in different ways and in different regions. Some dominate manufacturing. Others control energy routes, rare materials, or critical technologies. A few shape global finance or digital infrastructure.

What’s important is that these powers don’t all play the same game. One may avoid military confrontation but aggressively expand trade and infrastructure. Another may focus on regional security while staying economically cautious. Some use diplomacy and investment; others rely on pressure and deterrence.

This creates overlapping spheres of influence rather than clean borders. Countries increasingly hedge their bets—trading with one power, securing energy from another, and relying on a third for security guarantees. Loyalty becomes flexible, transactional, and temporary. Alliances still matter, but they are less automatic than they once were.

Economics as a Battlefield, Not a Neutral Space

Global power today is deeply tied to economics, but not in the old free-market sense. Trade, currency systems, and supply chains have become tools of leverage. Sanctions, export controls, tariffs, and investment restrictions are now standard weapons, used not just in crises but as ongoing pressure mechanisms.

Control over key nodes matters more than total output. Semiconductor manufacturing, energy chokepoints, shipping routes, and food production all carry strategic weight. A country doesn’t need to be the largest economy to be indispensable; it just needs to sit in the right place within the system.

This is why economic decoupling is such a powerful—and dangerous—trend. As nations try to reduce dependence on rivals, they also fragment global markets. That fragmentation raises costs, increases instability, and forces smaller countries to choose sides, often against their own long-term interests.

Technology and the New Foundations of Power

Technology has quietly rewritten the rules of influence. In the past, power was visible: fleets, factories, territory. Now much of it is invisible—algorithms, data flows, satellite networks, cyber capabilities. A small group of engineers can have more impact than an armored division.

Artificial intelligence, space systems, cyber warfare, and digital surveillance reshape how states compete. Control over platforms matters as much as control over land. Whoever sets technical standards—whether for 5G networks, AI models, or digital payments—locks in long-term influence.

This also lowers the barrier to entry for disruption. Smaller states, and even non-state actors, can punch above their weight by exploiting vulnerabilities rather than matching strength. That makes power less predictable and more volatile, with fewer clear rules and more gray zones.

Demographics, Resources, and the Long Game

Power shifts aren’t only driven by policy choices; they’re driven by time. Demographics may be the most underestimated factor. Countries with young, growing populations face different futures than those aging rapidly. Labor supply, military recruitment, consumer markets, and social stability all flow from population trends.

Resources add another layer. Water scarcity, energy transitions, and access to critical minerals shape geopolitical leverage. Countries rich in oil once dominated energy politics; now lithium, rare earth elements, and manufacturing capacity matter just as much. Geography hasn’t disappeared—it has simply changed meaning.

Some nations are positioning themselves decades ahead, investing in education, infrastructure, and technological independence. Others are trapped managing short-term crises, slowly losing influence without a dramatic collapse. Power often shifts quietly, long before headlines catch up.

Regional Power Centers Are Redrawing the Map

One of the clearest signs that global power is shifting is the growing importance of regional heavyweights. Instead of waiting for approval or protection from distant superpowers, countries are asserting influence closer to home. In some cases, this fills a vacuum. In others, it creates new friction.

In East Asia, economic gravity has pulled supply chains, trade routes, and investment flows toward the region. Manufacturing ecosystems there are dense, fast, and deeply interconnected. Even nations that worry about security tensions still depend on these networks because replacing them would take decades, not years.

In the Middle East, power is no longer defined only by oil exports or military alliances. Regional players now compete through diplomacy, media influence, proxy conflicts, and economic diversification. Some are trying to reinvent themselves as logistics hubs or technology investors, betting that relevance in the next era won’t come from energy alone.

Africa and Latin America, long treated as peripheral, are becoming strategic battlegrounds for influence. Infrastructure projects, mining rights, agricultural land, and digital connectivity are all contested spaces. The shift here isn’t about immediate dominance, but about long-term positioning—who builds the roads, controls the ports, and sets the rules before growth accelerates.

The Quiet Power of Non-State Actors

States are no longer the only meaningful players in global power dynamics. Corporations, financial institutions, tech platforms, and even loosely organized networks can shape outcomes once reserved for governments.

Large technology companies influence how information moves, how money is transferred, and how public opinion forms. Their policies can affect elections, social stability, and international relations, sometimes faster than any diplomatic channel. While they don’t fly flags or sign treaties, their decisions ripple across borders.

Financial actors also carry enormous weight. Investment flows can stabilize or destabilize economies. Credit ratings can punish governments overnight. Markets often react to signals faster than policymakers can respond, turning economic perception into a form of power in its own right.

Even individuals matter more than they once did. Whistleblowers, hackers, influencers, and entrepreneurs can disrupt narratives or systems on a global scale. Power has become more distributed, but also harder to control.

Information, Narrative, and Psychological Influence

Modern power is deeply tied to perception. Controlling territory matters, but controlling the story about that territory may matter more. Information warfare is now a permanent feature of global competition, not an occasional tactic.

Narratives shape legitimacy. They influence which actions seem justified, which alliances feel natural, and which threats appear urgent. Social media accelerates this process, rewarding emotional impact over accuracy and speed over reflection. A single viral moment can undo years of diplomatic work.

This doesn’t mean truth no longer matters, but it competes in a crowded and hostile environment. Governments invest heavily in shaping narratives, both at home and abroad, because public opinion has become a strategic resource. Winning without convincing people you’ve won is no longer possible.

Military Power Still Matters—Just Differently

Despite all these changes, military power has not disappeared. What has changed is how it’s used and what it can achieve. Large-scale invasions are costly, unpredictable, and politically risky. As a result, states rely more on deterrence, proxy conflicts, and limited engagements.

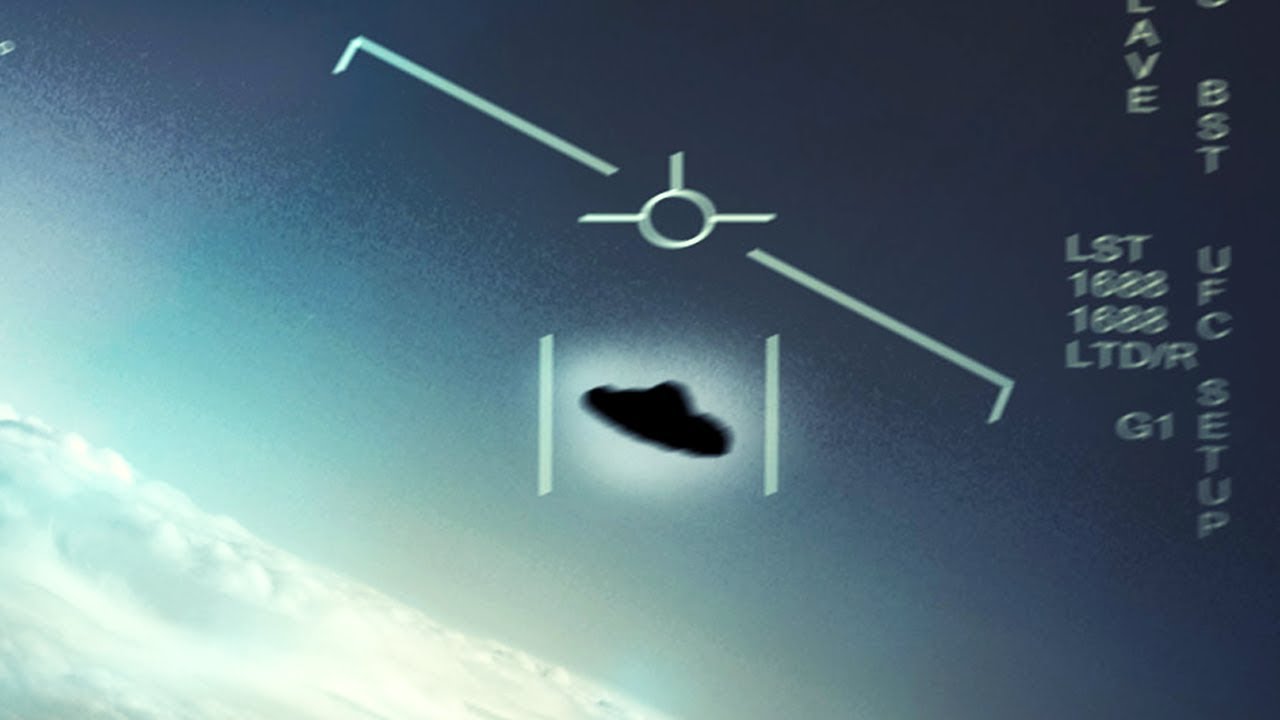

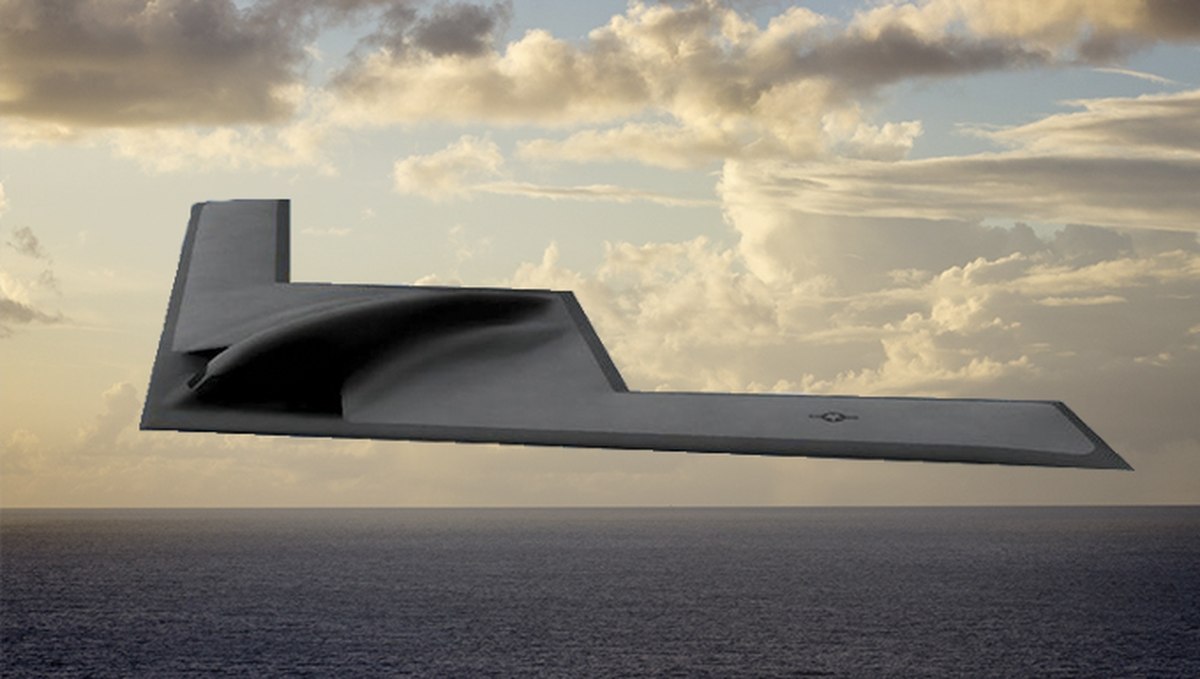

Precision weapons, drones, cyber operations, and space-based assets allow for influence without full-scale war. At the same time, these tools blur the line between peace and conflict. Attacks can be denied, delayed, or disguised, making escalation harder to manage.

This environment favors adaptability over sheer size. Militaries that can integrate technology, intelligence, and rapid decision-making gain an edge, even if they are smaller on paper. Power becomes less about overwhelming force and more about timing, coordination, and resilience.

What This Shift Means for Smaller Countries

For countries that are not global powers, this new landscape is both an opportunity and a risk. On one hand, no single actor can dictate terms as easily as before. Smaller states can negotiate, diversify partnerships, and extract benefits from competing interests.

On the other hand, ambiguity is dangerous. When rules are unclear and alliances are flexible, miscalculations become more likely. Smaller nations may find themselves pressured to choose sides or absorb shocks they didn’t create, especially during economic or security crises.

Success increasingly depends on strategic clarity. Countries that understand their strengths—geography, resources, human capital—can carve out influence disproportionate to their size. Those that rely on outdated assumptions about loyalty or protection risk being left behind.

Living Through a Transition, Not an Endpoint

Perhaps the most important thing to understand is that this shift is ongoing. There is no final destination yet. History rarely moves in straight lines, and power transitions are often uneven, marked by periods of confusion and instability.

The old order hasn’t fully collapsed, but it no longer works as it once did. The new one isn’t fully formed, but its outlines are visible. This in-between phase is uncomfortable because it offers fewer certainties and more contradictions.

What replaces the old system will depend on choices being made now—about cooperation, competition, technology, and trust. Global power is not just moving from one place to another. It’s being redefined in real time, by forces that don’t always announce themselves, but reshape the world all the same.