When people talk about the most feared aircraft on the planet, they almost always end up at the same name: the B-2 Spirit. From a distance it looks unreal, more like a piece of science fiction than a traditional airplane – a dark, boomerang-shaped silhouette gliding silently across the sky. Yet behind that strange shape is a machine designed to do something very specific and very chilling: slip through the most advanced air defenses on Earth, travel thousands of miles, and deliver a precise, devastating strike before anyone has time to react.

The B-2 was born out of the final, tense decades of the Cold War. Its original job was straightforward and terrifying – fly deep into Soviet territory, penetrate layered radar networks, and deliver nuclear weapons against heavily defended targets that older bombers simply could not reach. To do this, engineers and scientists had to build something radically different: a flying wing whose shape, materials, and engine layout were all tuned to make it almost invisible to radar.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, many people thought the time of gigantic, nuclear-focused bombers might be over. Instead, the B-2 quietly shifted into a new role. Rather than sitting in the background as a last-resort nuclear platform, it became a precision conventional bomber used in real wars. It made its combat debut in 1999 during NATO operations over Kosovo, flying from the United States to Europe and back in single missions, then went on to strike targets in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and against other hardened or well-defended sites that demanded something special.

Two decades later, B-2s have become a central part of how the United States signals power and deterrence. You see them forward-deployed to Guam to send a message to North Korea, you see them mentioned whenever tensions rise with China or Russia, and you occasionally catch them doing dramatic flyovers at major sports events back home. They have become both a practical weapon and a symbol: a reminder that if the US wants to hit something far away, through dense defenses, with very little warning, it has a tool built exactly for that.

What makes this bomber so dangerous isn’t just one thing. It is the combination of stealth, range, payload, sensors, and mission flexibility – plus the small, highly trained crew that manages all of it for tens of hours at a time. To understand why the B-2 still matters, even in an age of missiles and drones, it helps to look at how it was designed, what it can carry, where it has been used, and how it fits into the future of American air power.

From Secret Cold War Project to Public Rollout

The public first saw the B-2 in 1988, when it was revealed at Palmdale, California. By that point, it had already been years in the making under highly classified programs focused on low-observable aircraft. Designers at Northrop (later Northrop Grumman) had been experimenting with flying wings since the mid-20th century, and the B-2 was the culmination of those old ideas combined with modern computing, radar science, and new materials.

Originally, the US Air Force imagined a much larger fleet. Early plans talked about well over a hundred B-2s, then the number was trimmed to dozens, and after the Cold War ended the order was slashed again. In the end, only 21 aircraft were built. One crashed in 2008, and another has been effectively removed from service after being badly damaged in 2022, leaving 19 airworthy B-2s today.

That tiny fleet size is part of why the aircraft is so famous. Each bomber costs well over a billion dollars even before you start counting the development program behind it, and each one demands constant care: hangars with special climate control for its coatings, highly skilled maintainers, and careful handling of every system. The tradeoff is that when a B-2 takes off on a real mission, it does things that would require many conventional aircraft to even attempt.

Flying Wing: Shape, Stealth, and Aerodynamics

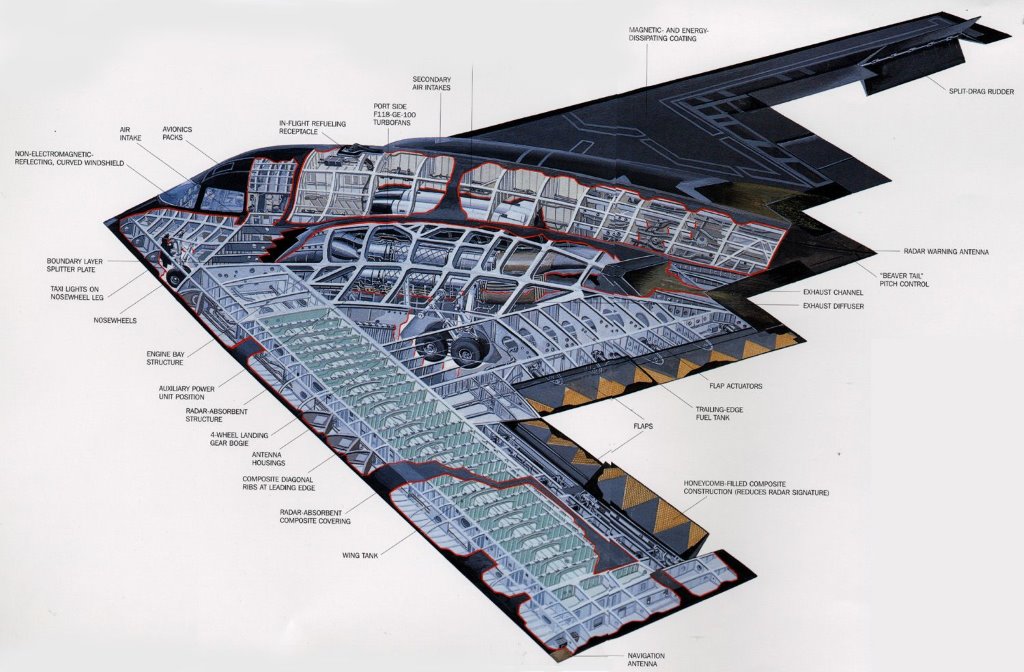

The most striking thing about the B-2 is its shape. It is a pure flying wing: no visible fuselage sticking out, no vertical tail to catch radar waves, and no separate horizontal stabilizer at the back. This layout does several jobs at once.

First, it reduces drag and improves range. Because so much of the aircraft’s surface area is part of the lifting wing, the design is highly efficient; far more of the aircraft’s weight is converted into useful lift, rather than being wasted on surfaces that just add drag.

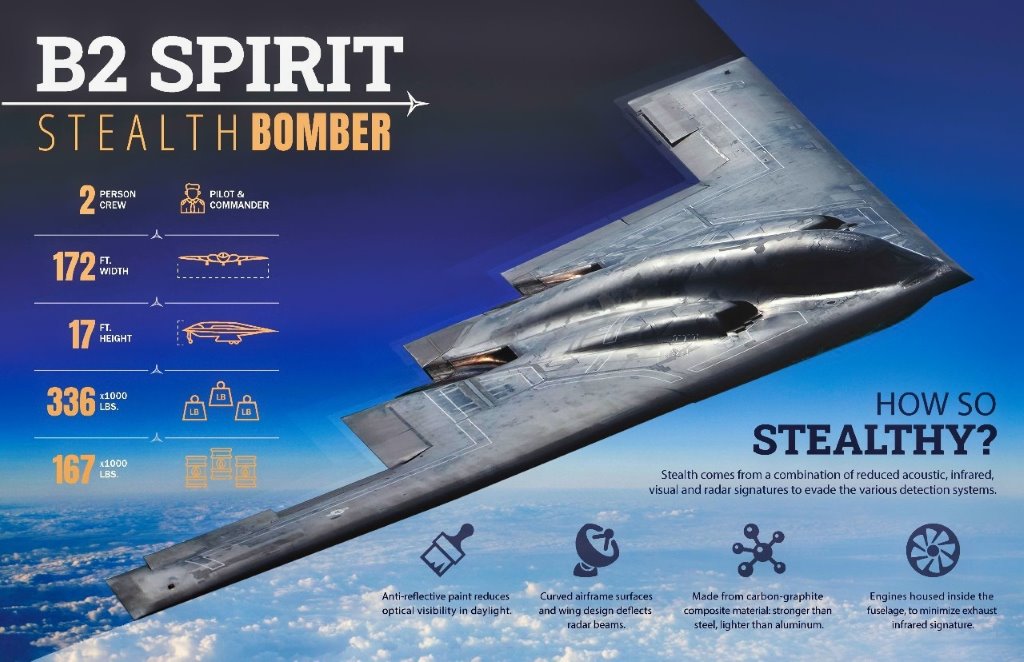

Second, and more importantly, the shape attacks radar from the start. Traditional planes have vertical tails, sharp corners, and other features that reflect radar pulses straight back to the source. The B-2 is carefully sculpted so that incoming radar waves are scattered away, not bounced directly back. The edges of the aircraft are swept at specific angles, and the surfaces are smoothed and blended to avoid abrupt transitions. Sources suggest its radar cross-section is roughly comparable to a small object rather than a heavy bomber, even though it has a wingspan of about 172 feet (around 52 meters).

On top of that shape, the B-2 uses radar-absorbent materials and special coatings. The exact formulas and techniques are classified, but the general idea is simple: instead of reflecting radar energy, parts of the aircraft absorb and dissipate it as heat, reducing what returns to enemy sensors. Even the air intakes and engine exhaust areas are carefully shielded and blended, hiding the turbines from radar and trying to mask the heat signature.

The result is an aircraft that can approach heavily defended territory at medium or high altitude, where traditional bombers would be under intense threat, and still be very difficult to detect and track.

Engines, Performance, and Extreme Endurance

Under that smooth surface sit four General Electric F118-GE-100 turbofan engines buried deep within the wing. Each engine produces roughly 17,300 pounds of thrust, giving the B-2 enough power to cruise at high subsonic speeds – roughly up to about Mach 0.95, or around 630 mph (about 1,010 km/h) at altitude.

On a single fuel load, the B-2 can fly more than 6,000 nautical miles (over 11,000 km) without refueling. With aerial refueling, its effective range is limited less by fuel and more by crew endurance and maintenance planning. That’s why you see stories of B-2 missions lasting well over a full day.

One often-cited example is a 34-hour round trip from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri to Libya and back, with B-2s refueled in the air multiple times along the way. Other missions have pushed even further. During the early days of the war in Afghanistan, B-2s flew record-breaking flights exceeding 40 hours, landing briefly with engines still running before taking off again to return home, turning the total mission time into something closer to 70 hours.

Inside, the aircraft is flown by a crew of just two: a pilot and a mission commander. On ultra-long missions, they rotate duties, eat, rest in place, and manage a complex flow of refueling hookups, route adjustments, target revisions, and coordination with other forces. It’s not glamorous – more like an airborne marathon – but this ability to lift off from the continental United States, strike anywhere on the globe, and return without landing in theater is a huge part of what makes the B-2 strategically valuable.

Weapons Load: Precision and Nuclear Deterrence

The B-2’s danger doesn’t come from sheer speed or acrobatic agility; it comes from what it carries. The aircraft can haul more than 40,000 pounds (over 18,000 kg) of ordnance in two internal bomb bays. That space can be filled with a mix of conventional and nuclear weapons, depending on the mission.

On the nuclear side, the B-2 was designed to deliver gravity bombs such as the B61 series and, historically, the large B83 bomb. Its stealth, range, and ability to approach from unexpected directions turned it into a central part of the US nuclear deterrent, able to threaten high-value targets even behind sophisticated air defenses.

For conventional warfare, the B-2 has become a precision strike platform. It can carry:

-

GPS-guided Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAMs) in 500-, 1,000-, and 2,000-pound classes

-

Larger penetrating weapons designed to break hardened bunkers and deeply buried facilities

-

Advanced stand-off missiles and long-range precision weapons in some configurations

Because all of this is carried internally, the aircraft stays stealthy throughout most of the mission. The only time its radar signature grows significantly is when the bomb bay doors open, and the doors are designed to snap open and shut quickly to limit that window.

That combination – stealthy approach, large payload, precision guidance – lets a very small number of B-2s achieve what would normally require dozens of conventional aircraft, support assets, and defensive escorts.

Avionics, Sensors, and Electronic Survival

Stealth gets the B-2 close. Its onboard systems help it survive, navigate, and actually carry out the strike.

At the heart of the aircraft’s mission systems is an advanced multi-mode radar, often referred to as the AN/APQ-181. It can map terrain, track targets, support low-visibility navigation, and integrate with the bomber’s weapons systems. This radar works alongside a digital navigation suite that combines GPS, inertial navigation, and terrain-following capability so the aircraft can fly precise routes even in darkness or bad weather.

The B-2 also carries a Defensive Management System (DMS) that listens for enemy radar and other emissions. When hostile systems illuminate or start searching, the DMS helps the crew understand what’s out there, where the threats are located, and how best to route around or through them. The system has been upgraded over time to handle newer types of air defenses and to feed better information into mission replanning tools, so crews can adjust their path mid-flight rather than relying entirely on pre-planned routes.

All of this is wrapped in heavy classification. The exact radar frequencies, tactics, and countermeasure techniques are closely guarded, because the bomber’s survivability depends on keeping adversaries guessing about what it can and can’t evade.

Combat Debut and Real-World Missions

The B-2’s move from nuclear-only concept to practical conventional bomber began in the late 1990s. During the Kosovo War in 1999, B-2s operating from Whiteman loaded up with precision weapons, flew across the Atlantic, struck targets in Serbia, and flew back home in a single continuous mission. That combat debut demonstrated two important things at once: the aircraft’s ability to penetrate defended airspace and its ability to project power globally without relying on local bases.

Since then, B-2s have appeared in almost every major campaign where the US wanted to send a clear message and hit high-value targets quickly and accurately. They struck Taliban and Al-Qaeda targets in Afghanistan, hardened command and control nodes in Iraq, and critical air-defense and leadership facilities in Libya. The bomber has reportedly been used against deeply buried or heavily fortified sites that require specialized munitions and a very precise delivery.

More recently, B-2s have continued to feature in long-range operations. Public reporting in 2025 described a major mission in which seven B-2s took part in strikes against Iranian nuclear infrastructure, flying a marathon round trip from their home base in Missouri with extensive mid-air refueling support.

In each of these cases, the bomber isn’t acting alone. It’s part of a wider package of fighters, support aircraft, intelligence assets, and cyber capabilities. But it tends to sit at the center of the opening moves, used where the combination of stealth, precision, and payload matters most.

Global Presence: Guam, Deterrence, and Signaling

Beyond actual combat, B-2 deployments are often used as a political signal. When tensions in the Asia-Pacific region rise, the US sometimes sends B-2s to Andersen Air Force Base in Guam. From there, they can fly training missions, exercise with regional allies, and demonstrate that they can reach important targets across the Western Pacific, including areas around North Korea or, in a broader strategic sense, China.

Similar deployments or overflights send messages to Russia and other potential adversaries. The sight of a B-2 at a foreign air base, or the knowledge that it has flown a mission over a sensitive region, is meant to remind other governments that distance and dense air defenses are not guarantees of safety.

At home, the aircraft appears in a very different role: ceremonial flyovers of big sporting events, national celebrations, and air shows. For most people, that’s their only direct experience of the bomber – a dark triangle gliding overhead for a few seconds. Behind that brief glimpse, though, lies the same stealthy long-range machine that flies around the world when ordered.

Why There Are So Few B-2s

Part of the B-2’s mystique comes from its rarity. Nineteen aircraft is an incredibly small fleet for something so central to a country’s long-range strike capability.

There are a few reasons for that. First is cost. The bomber was developed during a period of intense technological experimentation, and a lot of what went into it was brand new: stealth shaping, advanced coatings, sensitive electronics, and a complex support infrastructure. When you divide the total program cost by the number of aircraft actually built, you arrive at a unit price in the billions of dollars, making it one of the most expensive aircraft projects in history.

Second is timing. When the Cold War ended, pressure to cut expensive strategic programs grew quickly. Plans for larger fleets of B-2s were scaled back dramatically, and the US chose to keep older B-52s in service alongside smaller numbers of newer aircraft rather than replace everything at once.

Finally, the aircraft is technically demanding to maintain. Keeping its stealth coatings in good condition, servicing its systems, and ensuring high mission readiness all take time, money, and specialized skills. That doesn’t mean the aircraft is unreliable; it just means that every hour of flight time is supported by a lot of work on the ground.

Life After the Spirit: Enter the B-21 Raider

As effective as the B-2 is, it is not intended to last forever. The US Air Force has already begun introducing its successor, the B-21 Raider, another stealth bomber developed by Northrop Grumman. The plan is for the B-21 to gradually take over the penetrating strike role as B-2s and B-1Bs are retired in the early 2030s, leaving a future bomber force built around B-21s and upgraded B-52s.

The B-21 is designed to be more maintainable, more flexible, and more affordable per aircraft, while still retaining the key strengths that made the B-2 so valuable: stealth, long range, and the ability to carry both conventional and nuclear weapons. Early test flights and official statements suggest it will operate as a “sixth-generation” platform with an open systems architecture, making it easier to integrate new weapons, sensors, and software over time.

For the B-2, this doesn’t mean it suddenly becomes irrelevant. Until the new bomber is fully fielded in large numbers, the Spirit remains the tip of the spear for certain missions. It continues to train, deploy, and occasionally fight, carrying on the role that was carved out for it during the final years of the Cold War.

A Bomber That Changed What Was Possible

In the end, what makes the B-2 so dangerous isn’t that it can fly slightly faster than another aircraft or carry a few more bombs. Plenty of bombers in history have carried huge payloads or flown long distances. What sets the Spirit apart is the way it combines stealth, global reach, precision, and nuclear as well as conventional capability into a single airframe – and then backs that combination with trained crews and a support system built to use it strategically, not just tactically.

It rewrote expectations for what a bomber could do: take off from the middle of the United States, disappear into the night, cross oceans and hostile airspace, strike enemies that thought they were safe behind modern defenses, and then slip quietly home. Even now, with newer designs on the horizon, that basic idea remains extremely hard for any potential adversary to counter.

As long as it remains in service, the B-2 Spirit will sit in a strange space between legend and active duty: a rare aircraft that most people will never see up close, but whose existence shapes strategic calculations all over the world.