The Vikings were a wide mix of Scandinavian seafarers and settlers from what is now Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, active roughly from around 790 to about 1100 CE. They didn’t just leave a few dramatic stories behind—they pushed changes into the everyday lives of people across Europe, and their presence could be felt even down toward Mediterranean regions. Still, one thing matters if you want to be accurate: all Vikings were Scandinavian, but not all Scandinavians were Vikings.

The word Viking is best understood as a label for a particular kind of activity, not a label for everyone living in Scandinavia. It applied most strongly to people who went to sea with the goal of gaining wealth through armed raids in foreign lands. That’s why, in many sources, the term shows up most often in English writing rather than as a universal self-description used by every neighboring culture. Many Scandinavians lived ordinary lives as farmers, craftsmen, fishers, traders, and herders. Those who traveled for commerce rather than raids were often called Northmen, Norsemen, or similar names tied to their place of origin.

From the late 8th century onward, Viking raiding grew into a long-running phenomenon that lasted about three centuries. They struck coastlines and river routes, hit inland towns, and also carried out far-reaching trade. Their journeys weren’t limited to the North Sea—Scandinavians traveled east into routes connected to the Byzantine Empire and, in some cases, entered service as elite soldiers known as the Varangian Guard, attached to the Byzantine Emperor. Whether through violence, settlement, trade, or military service, they left an imprint on almost every region they touched, especially in Scotland, Britain, France, and Ireland. Over time they founded Dublin, helped shape Normandy (literally “land of the Northmen”) in France, carved out the Danelaw in parts of Britain, and planted themselves in numerous Scottish communities where Scandinavian influence blended into local life.

THE SCANDINAVIAN CULTURE WAS ACTUALLY HIGHLY DEVELOPED & THE VIKING RAIDS ON OTHER NATIONS WERE ONLY ONE ASPECT OF THE CIVILIZATION.

Their later settlements in Iceland and Greenland pushed Scandinavian culture further across the North Atlantic, and those stepping-stone communities made longer voyages more realistic. Vikings became the first Europeans known to have reached North America and attempted settlement there. The site at L’Anse Aux Meadows in Newfoundland has been confidently identified as an early Viking settlement, and while people still debate other possible locations from Maine to Rhode Island—and sometimes even farther south—the broader point remains: their seafaring wasn’t a lucky accident, it was the result of skills, ships, and a culture that could support repeated long-distance travel.

A lot of the popular imagery around Vikings needs a little pruning. The famous horned helmet idea is almost certainly wrong for battlefield use. Horns would snag, unbalance, and basically turn a helmet into a handle for an enemy. If horned headgear existed in this world at all, it makes far more sense for ceremonies, storytelling, or symbolic display. And while Vikings were absolutely capable fighters—so much so that their name became linked with warfare and destruction in later imagination—that’s not the whole civilization. Scandinavian society was not a crude, empty backdrop with only raiding in it. It included detailed craftsmanship, long-distance commerce, complex social rules, lawmaking, religious practice, poetry, music, and an everyday life that was often much more organized than the stereotypes suggest.

Where the Name “Viking” Comes From

Where the word “Viking” actually comes from is still argued over by scholars, and the debate itself says something interesting: even the label we use most casually today is not as straightforward as people assume.

One traditional explanation is associated with Professor Kenneth W. Harl, who notes the word may connect to the Old Norse term vik, meaning a small bay, inlet, or fjord—exactly the kind of sheltered place where sea-raiders might hide ships and watch for targets. In that view, the geography of Scandinavia isn’t just scenery; it’s part of how raiding worked, since coves and narrow waterways offered protection and surprise.

Another line of thought comes from the philologist Henry Sweet, who suggested the word derives from an Old Norse term for “pirate.” That sounds blunt, but it fits the way outsiders often viewed these raids: fast-moving attacks by armed crews who struck suddenly, took goods and captives, and vanished back into the sea routes before a local defense could respond.

Professor Peter Sawyer offered a different argument that ties the term to a specific region: Viken, near the Oslo Fjord. Sawyer proposed that if Viking originally referred to people from Viken, it could help explain why English writers used “Viking” while many others didn’t. England was a natural destination for raiders crossing from that general area, especially for those who left home as exiles or fortune-seekers. Sawyer emphasized that while the same people appeared in many records, other cultures called them by other names.

That point is important: plenty of societies wrote about Scandinavian sea-raiders, but they often didn’t call them Vikings. Irish records sometimes described them as pagans or simply foreigners. French sources commonly used terms like Northmen. Slavic sources referred to them as the Rus, a name that later fed into “Russia.” German writers sometimes called them Ashmen, apparently referencing ash wood used in boats, a practical detail turned into an identity label.

What did Scandinavians themselves say? They used “Viking” more as a description of an action—an expedition of raiding—rather than a fixed ethnic badge. The Old Norse phrase fara i viking (“to go on expedition”) wasn’t just “to travel by sea.” It meant you were going out with weapons and intent, aiming for profitable targets abroad. Saying you were “going Viking” was basically an announcement: you were joining a raid, seeking plunder and status, and accepting the risks that came with it.

Life and Society in Viking Scandinavia

Viking culture, in the broad sense, was Scandinavian culture—because Vikings came out of that world—but Scandinavian society was not one single uniform lifestyle. It had layers, rules, and strong social boundaries, even if people could sometimes climb within them.

Society is often described as having three main classes. At the top were Jarls, an aristocratic elite with wealth, land, influence, and access to leadership. Karls formed the broad lower class of free people—farmers, skilled workers, and ordinary households who carried much of the economy and could sometimes gain status through success, marriage alliances, or military achievement. Thralls were enslaved people, and while Karls could sometimes improve their position, Thralls generally could not.

SLAVERY WAS WIDELY PRACTICED THROUGHOUT SCANDINAVIA & IS CONSIDERED ONE OF THE PRIME MOTIVATORS FOR THE VIKING RAIDS ON OTHER LANDS.

Slavery wasn’t a side detail—it was a system woven into labor, wealth, and power. Captives could be taken in raids, traded, or used as workers, and the demand for slaves and the profits tied to them helped fuel raiding expeditions. That’s uncomfortable, but it’s central to understanding why raiding could be attractive beyond simple “loot.” It wasn’t just about silver. It could be about human labor, household status, and the ability to expand production at home.

Women in Scandinavian society often had more recognized legal and economic freedoms than women in many neighboring cultures at the time. Women could inherit property, and if unmarried they could decide where and how to live. They could appear in legal disputes, represent themselves in certain contexts, and own businesses—breweries, taverns, shops, farms, and other working enterprises. In religious life, women could also hold a special position as prophetic figures associated with divine messages—linked in different traditions to Freyja or Odin—and there was not the same kind of centralized male priesthood structure that people imagine from later medieval Christian society.

Marriage, however, was still strongly shaped by family decisions. Marriages were arranged by the men of the clan, and individuals had limited freedom in choosing partners—women couldn’t freely choose, but neither could men in the way modern people mean it. Dress and jewelry generally reflected social class more than gender. Men and women of similar status could wear comparable quality clothing and adornment. Some sources note that earrings were not typically worn and were sometimes seen as “foreign” or lower-status affectations, though fashion and symbolism could vary regionally and across time.

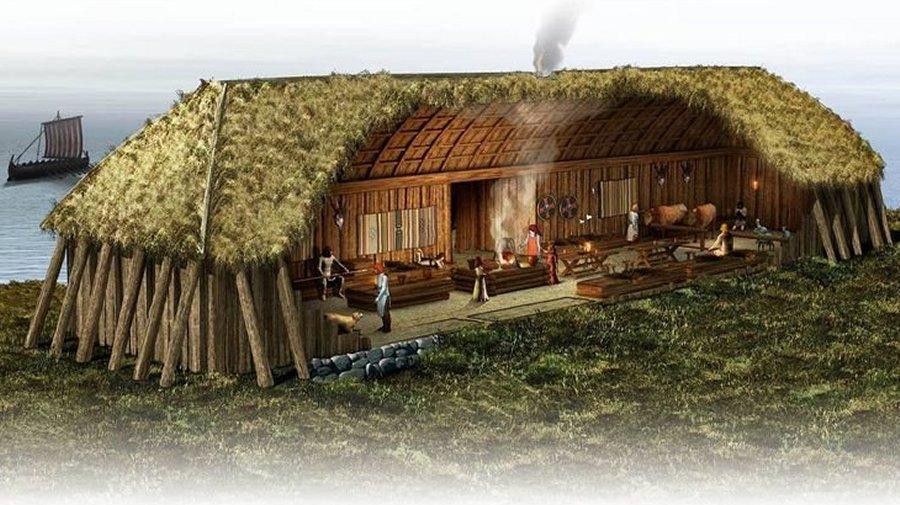

Daily life involved work that was both ordinary and surprisingly varied. Many Scandinavians were farmers, but the society also included blacksmiths, armorers, brewers, merchants, weavers, carpenters, instrument makers, drum-makers, poets, musicians, craftsmen, jewelers, and more. Trade mattered. Amber—fossilized resin—was a major product of the region, often found along Scandinavian shores and worked into jewelry or sold in partially processed form. It circulated widely and could reach powerful markets such as Roman and Byzantine spheres through trade networks.

Leisure wasn’t absent either. Scandinavians played sports and games, and festivals could bring communities together with food, music, storytelling, competition, and ritual. Activities included wrestling, swimming, hunting, climbing, javelin throwing, and mock combat. There was also a spectacle sometimes called horse-fighting, though the exact nature of it is unclear in many descriptions. A field game known as Knattleik—often compared loosely to hockey in the sense of energetic team play—was also enjoyed, alongside board games involving dice, strategy boards, and chess-like planning.

The “dirty savage” stereotype is another popular myth that doesn’t hold up well. Many Scandinavians took grooming seriously. Cleanliness could signal wealth and status, and grooming tools appear in archaeological finds. When trade ties grew stronger with eastern markets, elite Jarls could wear expensive jewelry and even silk, styling hair with braids and maintaining a well-groomed appearance. Fine cloaks, detailed metalwork, and carefully crafted accessories weren’t rare in the upper class; they were part of showing social standing.

Hygiene also intersected with belief. Grooming and keeping nails trimmed wasn’t only about appearance; it had spiritual meaning connected to Ragnarök. There was a belief that the ship Naglfar—associated with end-times and the great serpent Jormungand—was built from the nails of the dead. Dying with long, untrimmed nails was seen as contributing material to that ship and, in a sense, pushing the world closer to its catastrophic ending. Whether every person truly lived with that fear every day is hard to prove, but the story shows how mythology could reach into practical behavior.

Beliefs and Gods of the Norse World

In Norse religious thought, the end of the world was fated, but human struggle still mattered. Life was a gift, and the point was not to sit quietly waiting for doom, but to live in a way that proved worthy—through courage, loyalty, endurance, and personal honor. The Norse gods were believed to have arrived in Scandinavia through broader Germanic migrations, with roots tied to periods stretching back toward the Bronze Age. They were not gentle gods who promised endless safety. They were fierce, limited, and intensely alive—beings who knew that their time would end, and who lived with a kind of grim energy because of it. Followers were encouraged to adopt the same attitude: live fully, act decisively, and meet hardship with strength.

Much of what we know comes from two major sources recorded later: the Poetic Edda (built from older oral traditions, especially associated with the 9th and 10th centuries) and the Prose Edda (often dated around the early 13th century), which gathered and organized tales rooted in earlier storytelling. Because these were written down after many generations of oral transmission, and often in Christianized contexts, they must be read carefully. Still, they preserve core myths and themes that shaped the worldview.

The creation story begins in a world of ice and emptiness, where the giant Ymir exists by the grace of the cow Audhumla. Audhumla feeds Ymir with milk flowing from her four udders, and she herself survives by licking the ice. Her licking frees a trapped figure, the god Buri, who later has a son named Borr. Borr marries Bestla, the daughter of the frost giant Bolthorn, and together they produce Odin, Vili, and Vé.

Those gods unite, kill Ymir, and use his body as raw material to create the world. From this cosmic violence comes order: land, sea, sky, and structure. Later, the first human beings—Ask and Embla—exist in a kind of unfinished state until the gods breathe spirit into them and grant them the qualities needed for human life. That story isn’t only a myth about origins; it frames the universe as something built through struggle and shaped by deliberate action.

The world was imagined as centered on Yggdrasil, a vast tree holding nine realms. The most famous are Midgard (the human world), Asgard (home of the gods), and Alfheim (home of the elves). Beneath Midgard lies Niflheim, associated with those who died in dishonor or misfortune. The afterlife wasn’t a single destination. Heroic men who died in battle could be taken to Valhalla, Odin’s hall, while heroic women—especially those who died in childbirth—could go to the Hall of Frigg in Asgard, spending eternity in the company of Odin’s wife. These ideas offered meaning and structure, but also reinforced social values around courage, honor, and endurance.

Order, in this worldview, is not permanent. The frost giants remain a looming threat, living in Jotunheim and constantly pressing against the borders of the worlds. Chaos is never fully defeated; it is postponed. The gods establish the cosmos after beating back the giants, but they know a final day is coming when destruction breaks through. That final day is Ragnarök, the twilight of the gods, when the world’s boundaries collapse and the old order is torn apart.

At Ragnarök, the wolf Skoll devours the sun and his brother Hati consumes the moon, dragging the world into darkness. Fenrir, the great wolf, ravages the realms. Heimdall sounds his horn, summoning the gods to battle, and Odin calls the heroes from Valhalla to stand beside the divine defenders of creation. The gods fight with courage, but they fall, and the universe is consumed by flame before sinking into the primordial waters. Yet the story does not end with total annihilation. After destruction comes renewal: a new world rises, and the cycle continues, suggesting that existence is bigger than any single age.

Religious life in Scandinavia wasn’t centered on a strict priestly hierarchy, at least not in the way later Christian societies were. The gods were honored through actions, vows, and communal practice. Women with spiritual gifts, often called Volva, were believed to receive divine messages and translate them for others. There were temples in some places, but worship frequently took place in natural settings—groves, stones, springs, and landscapes associated with specific powers. The stories, rituals, and warnings about Ragnarök were passed along orally for generations and were later written down in Iceland, famously by Snorri Sturluson, who lived in the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

Ships, Seafaring, and the Raiding Era

Norse mythology didn’t just sit in the background; it could shape behavior and justify action. Many Viking warriors saw themselves as living in a way that mirrored the gods—seeking danger, proving courage, and confronting forces they viewed as chaotic or hostile. When Vikings encountered Mediterranean and European religious life built around one all-powerful god, a savior figure, priests, churches, written rules, and a tightly managed religious structure, it could seem strange, even threatening. Norse belief didn’t resonate with that system. The Norse gods had different roles, different limitations, and a cosmic drama that made struggle feel meaningful rather than sinful.

Once Scandinavians mastered advanced shipbuilding and began to go on raiding expeditions, they often attacked Christian communities with brutal intensity. Yet there’s a twist that complicates the story: Scandinavian settlers in foreign lands sometimes adopted Christianity after arrival. So while early raids could be marked by ruthless violence, later settlement could involve blending, conversion, and practical adaptation.

Shipbuilding itself had deep roots. Carvings dated as far back as roughly 4000–2300 BCE suggest early knowledge of boat construction. Those early vessels were likely paddled, lacked keels, and were risky for long sea crossings, yet evidence suggests people still made ambitious journeys. Over time, ships evolved. More serious development beyond small ferry-style boats appears around 300–200 BCE, and later improvements came through contact with wider trade networks, including Roman traders and Celtic and Germanic merchants who had access to Roman technology. One important early seaworthy ship is the Nydam ship from Denmark (built roughly 350–400 CE), which could navigate the sea well even though it did not use a sail.

Long before the classic Viking longship era truly erupted, Scandinavian traders had already founded communities in Europe and, in some cases, assimilated into Christian cultures. Over time, some forgot the older stories, gods, and rituals. Kenneth Harl notes that by around 625 CE, West Germanic relatives of the Scandinavians had converted to Christianity and begun to lose memory of their older myths. Between roughly 650 and 700 CE, fresh Christian cultures solidified in England, the Frankish world, and Frisia, creating a “parting of the ways” between the Scandinavian heartland and the post-Roman Christian states.

That separation wasn’t only political—it was conceptual. The Christian god was presented as omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent. The Norse gods were different: powerful, yes, but limited, shaped by fate, and defined by roles and conflicts. In Norse thinking, the universe teemed with spirits and forces, and life felt like an arena for risk and achievement. For many Christians, the world was a fallen place of sin watched over by a single deity. Those differences mattered when Vikings encountered Christian communities.

There’s also a moral contradiction that needs to be faced directly. In theory, it could be considered dishonorable for a Norse warrior to kill unarmed civilians and steal their possessions. And yet that is exactly what Vikings did across the raiding era. One explanation offered in many discussions is that the victims were not Norse and not bound by Norse social rules, so those rules were not applied. This is not “excusing” the violence—it’s describing a worldview that could allow it. When Vikings attacked Lindisfarne in 793 CE, they killed monks and took valuables, actions that would have been treated as serious crimes if done against fellow Scandinavians. Against foreign monks, they could be framed as obstacles to wealth, and the raid could even be interpreted as proof that the Christian god lacked power to defend his own sacred sites.

Expansion and Legacy

To many Christians in Europe, Viking raids looked like punishment from God—an echo of earlier interpretations of invasions, such as the Huns striking the Roman world centuries before. In Britain, Alfred the Great (reigned 871–899 CE) responded with reforms, including efforts to strengthen education, discipline, and religious practice, partly to improve society and partly to calm fears of divine wrath. Alfred also used Christianity as a political tool in negotiations, making baptism and conversion part of treaty terms with Viking leaders.

A famous example comes after the Battle of Eddington in 878 CE, where Alfred defeated Viking forces under Guthrum. Under the treaty terms, Guthrum and thirty of his leading men were required to accept baptism and conversion. This shows how religion could become a diplomatic lever, not just a private faith.

In France, Charlemagne (crowned emperor 800 CE, died 814 CE) took a more aggressive approach, pushing military campaigns that aimed to impose Christianity and crush sacred sites tied to older beliefs. Some historians argue that Charlemagne’s holy wars intensified Viking hostility and contributed to the savagery of later raids. Others point out that Viking attacks in Britain and Ireland began earlier than Charlemagne’s major campaigns, so his actions can’t fully explain the phenomenon. Still, it’s hard to deny that forced conversion efforts and destruction of sacred places created bitterness, making Christianity look like an enemy ideology rather than a neutral faith.

Over time, Viking activity in Europe shifted. Early sea-raiders could resemble pirates: small groups striking quickly for portable wealth. Later, larger armies arrived under skilled leaders, conquering territory, setting up governance, and founding long-term communities. Eventually, many Vikings assimilated into local populations, marrying into families, adopting languages, and blending customs. The Viking Age becomes easier to understand when you see it as a progression—from raiding, to settlement, to integration—rather than a single unchanging behavior.

This period produced many famous leaders. Among them are Halfdan Ragnarsson (also called Halfdane), his brother Ivar the Boneless, Guthrum, Harald Bluetooth, Sven Forkbeard, Cnut the Great, and Harald Hardrada. It also produced explorers remembered for pushing outward across the North Atlantic, such as Erik the Red and Leif Erikson, connected with Greenland and voyages that reached North America.

The Viking Age didn’t end because Vikings were crushed in one final battle. They were never defeated all at once, and no single event shut the door completely. Many scholars point to 1066 CE as a symbolic endpoint because Harald Hardrada was killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, but raids and Scandinavian involvement abroad did not instantly stop the moment he fell. Instead, the Viking Age faded due to multiple pressures: stronger European kingdoms, better coastal defenses, changing trade patterns, shifting power structures, and—perhaps most importantly—the Christianization of Scandinavia during the 10th and 11th centuries. As Norse religion declined, one of the major ideological engines that encouraged raiding and heroic risk-taking weakened. In the new religious framework, there was far less spiritual meaning attached to “going Viking.”

The Vikings influenced every culture they touched in ways that went far beyond warfare. Their impact shows up in architecture, language, place names, infrastructure, poetry, ship technology, military organization, clothing styles, and everyday food and tools. Medieval writers often depicted them as murderous heathens, and later ages sometimes flipped the script, romanticizing them as noble savages. Both images miss the real texture of their world. Vikings could be brutal, and their raids were devastating, but they were also part of a sophisticated society with skilled craftsmanship, complex laws, deep storytelling traditions, and a worldview that made risk feel like a calling. In their own minds, shaped by their beliefs, a raid could look like a gamble where everything was worth winning and little was worth fearing.