Heavy bombers are large bomber aircraft built to carry the heaviest air-to-ground weapon loads of their era over the longest practical ranges. In every generation, these machines sit at the top of the bomber food chain: big airframes, powerful engines, long legs, and the ability to haul massive quantities of bombs or stand-off weapons toward distant targets. Because of this combination of size, power, and reach, heavy bombers have usually been among the most complex and expensive military aircraft in service at any given time.

In the first half of the 20th century, “heavy bomber” usually meant a multi-engine aircraft designed to drop large loads of conventional bombs on strategic targets such as factories, shipyards, cities, and transportation networks. In the second half of the century the concept evolved: heavy bombers were increasingly optimized for nuclear delivery and long-range deterrence, and the term “strategic bomber” began to replace “heavy bomber” in doctrine and everyday language. Strategic bombers might not always be physically larger than earlier piston-engined giants, but they were built to carry nuclear weapons halfway around the planet and deliver them with far greater precision and survivability.

Improvements in aircraft design and engineering—especially in engines and aerodynamics—meant that payload capacity grew dramatically, even when airframe size did not grow at the same rate. The largest bombers of World War I, such as the four-engined giants built by the Zeppelin-Staaken company in Germany, managed a payload of about 4,400 pounds (2,000 kg) of bombs, which was impressive for their day but modest by later standards. By the middle of World War II, however, even a single-engine fighter-bomber could carry a 2,000-pound (910 kg) bomb, and these agile aircraft began to take over many of the missions once assigned to light and medium bombers in the tactical bombing role. At the same time, advances in four-engined aircraft design allowed heavy bombers to lift far greater loads over thousands of kilometers, making genuine long-range strategic air campaigns possible.

One of the classic examples is the British Avro Lancaster, introduced in 1942, which routinely carried around 14,000 pounds (6,400 kg) of bombs on operations and, with special modifications, could handle outsized weapons up to roughly 22,000 pounds (10,000 kg). Its combat radius was about 2,530 miles (4,070 km), enough to hit deep targets in occupied Europe from bases in Britain. A little later, the American Boeing B-29 Superfortress entered service (1944), capable of hauling more than 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) of bombs over 3,250 miles (5,230 km). By the early 1960s, the jet-powered Boeing B-52 Stratofortress pushed the heavy bomber idea even further: flying at speeds up to roughly 650 mph (about 1,050 km/h), more than twice the Lancaster’s cruising speed, it could deliver an astonishing payload of about 70,000 pounds (32,000 kg) over a combat radius exceeding 4,400 miles (7,000+ km).

During World War II, mass-production techniques in the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union put large fleets of long-range heavy bombers into the air. For the first time, nations could attempt sustained strategic bombing campaigns aimed at systematically degrading an enemy’s war-fighting capacity. This culminated in 1945 when B-29s of the United States Army Air Forces dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, accelerating the end of the war in the Pacific and demonstrating the terrifying potential of heavy bombers paired with nuclear weapons.

The arrival of both nuclear weapons and guided missiles after World War II fundamentally changed military aviation and strategy. From the late 1950s onward, intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) increasingly took over the central nuclear deterrent role from manned heavy bombers. At the same time, new precision-guided weapons and nuclear-armed missiles small enough to be carried by fighter-bombers or multirole combat aircraft made it possible to deliver devastating strikes without relying solely on big, specialized bombers. As these trends accelerated through the late 20th century, the traditional heavy bomber’s position at the absolute core of strategic warfare gradually eroded.

Even so, heavy and strategic bombers have not disappeared. In conflicts from Vietnam to the Gulf War and beyond, aircraft like the B-52 have been used to deliver huge quantities of conventional ordnance, including carpet-bombing campaigns as well as precision stand-off strikes with modern guided weapons. Heavy bombers provide unique persistence, payload, and flexibility: they can loiter, retask mid-mission, and carry a mix of weapons that no smaller aircraft can match.

Today, only a handful of air forces still operate true heavy or strategic bombers: primarily those of the United States, Russia, and China. The U.S. relies on its triad of the B-52, B-1B, and B-2 (with the B-21 Raider being introduced), Russia fields types such as the Tu-95 and Tu-160, and China uses advanced versions of the Xi’an H-6 family as its main long-range bomber force.

World War I: first generation heavy bomber pioneers

The first heavy bomber in history actually began life as an airliner. Igor Sikorsky, an engineer educated in St. Petersburg and born in Kiev to a family of Polish-Russian background, designed the Sikorsky Ilya Muromets as a large passenger aircraft intended to fly comfortably between his birthplace and his new home. It briefly served this civil purpose until August 1914, when the outbreak of World War I changed everything. The Russo-Balt wagon factory converted the design into a bomber, replacing the German engines used on the airliner with British Sunbeam Crusader V8s to ensure supplies during wartime. By December 1914, a squadron of ten Ilya Muromets bombers was already striking German positions on the Eastern Front, and by the summer of 1916 around twenty were in service.

For its time, the Ilya Muromets was a remarkable machine. It featured four engines, an enclosed cabin, and heavy defensive armament including up to nine machine guns and a tail gun, which was a novelty in those early days of aerial warfare. Its size was such that its wingspan was only a few feet shorter than that of the much later Avro Lancaster, even though its bomb load was only about three percent of the Lancaster’s capacity. In the early years of the war, the Sikorsky bomber was effectively immune to German and Austro-Hungarian interception; enemy fighters lacked the performance and firepower to bring it down reliably.

In Britain, the Handley Page Type O/100 drew heavily on concepts that Sikorsky had proven. Similar in size and intent, the Type O/100 used just two Rolls-Royce Eagle engines yet could carry up to 2,000 lb (910 kg) of bombs. It was designed from the outset at the request of the Royal Navy, which wanted “a bloody paralyser of an aircraft” capable of threatening the German High Seas Fleet in its bases. Entering service in late 1916 and based near Dunkirk, the O/100 initially flew daylight raids on naval targets, even damaging a German destroyer. After one aircraft was lost, however, the type was switched to night operations, foreshadowing the nocturnal bombing campaigns that would become commonplace later on.

The improved Handley Page Type O/400 could carry a 1,650 lb (750 kg) bomb and formed the backbone of the first British attempts at long-range strategic bombing. Wings of up to 40 aircraft were assigned to the newly formed Royal Air Force (RAF) from April 1918, which used them to attack German railway hubs and industrial sites in an effort to disrupt war production and logistics. One O/400 was even detached to support T. E. Lawrence’s campaign in Sinai and Palestine, demonstrating how heavy bombers could be employed flexibly in distant theaters.

Germany’s Imperial Air Service developed its own heavy bomber capability with the Gotha series. The Gotha G.IV and its successors operated from occupied Belgium from the spring of 1917, staging long-range raids on Britain. Beginning in May 1917, they attacked London and coastal towns such as Folkestone and Sheerness. On 13 June 1917, a Gotha raid killed 162 civilians (including 18 children in a primary school) and injured more than 400 people in East London, shocking the British public and underscoring the psychological impact of heavy bombers. Initially, defenses against such raids were inadequate, but by May 19, 1918, when 38 Gothas attacked London, six were shot down and another crashed on landing—a sign that defensive tactics and technology were catching up.

German industry also produced a series of “giant” bombers known collectively as the Riesenflugzeug. These aircraft were impressive even by later standards, with multiple engines and enormous wingspans. Most were built in small numbers from 1917 onward, and some never saw combat. The most successful was the Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI, of which 13 entered service, bombing targets in Russia and London. Four were shot down and six lost in landing accidents, highlighting the risks of operating such large, delicate machines from primitive wartime airfields. Remarkably, the R.VIs were larger than the standard Luftwaffe bombers of World War II, emphasizing just how ambitious German heavy bomber designs had been even in World War I.

Britain’s Vickers Vimy, a long-range heavy bomber powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle engines, arrived too late to see substantial wartime service—only one had reached France by the time of the Armistice in November 1918. Its intended mission was to attack industrial and railway targets in western Germany, which it could reach thanks to a range of about 900 miles (1,400 km) and a bomb load slightly over a ton. The Vimy became famous not for its bombing exploits but for its postwar achievements. On June 14, 1919, a Vimy piloted by John Alcock and navigated by Arthur Whitten Brown made the first non-stop transatlantic flight from St. John’s, Newfoundland, to Clifden, Ireland, proving that large multi-engine aircraft could span oceans and hinting at future strategic possibilities.

Strategic bomber theory between the wars

In the years between World War I and World War II, airpower thinkers developed theories about how bombers—especially heavy and long-range bombers—could decide future wars almost single-handedly. Two core beliefs guided much of this thinking at the time.

The first was summed up in the famous phrase “the bomber will always get through.” Early interwar fighters, many still biplanes, enjoyed only a small speed advantage over bombers, and it was widely believed that they would not be able to overtake or outclimb heavily laden bombers in time to intercept them. Even more importantly, there were no effective long-range early-warning systems: radar was still experimental, and coastal observers or sound locators gave only vague and late indications of incoming raids. In theory, a determined bomber force could simply fly over enemy territory, release its load, and return with limited losses. In practice, technological developments such as radar, ground-controlled interception, and the transition to high-performance monoplane fighters gradually eroded this supposed advantage.

By the time World War II was under way, it became clear that unescorted heavy bombers suffered severe losses when facing modern fighters and radar-guided defenses. Without careful planning, electronic countermeasures, or strong escort fighters, formations of heavy bombers could be decimated. Only a few exceptionally fast or specialized aircraft, such as the de Havilland Mosquito light bomber, could truly rely on speed alone to slip past enemy defenses. Heavy bombers needed extensive defensive armament, including multiple gun turrets and gunners, which increased empty weight and reduced the space and weight available for bombs and fuel.

The second major belief was that strategic bombing—attacks on industrial capacity, power generation facilities, oil refineries, transportation hubs, and coal mines—could win a war by breaking an enemy’s ability to fight. Advocates argued that rather than grinding away at enemy armies in the field, air forces could attack the “vital centers” of an opponent’s war economy and force surrender through material collapse and psychological shock. This idea seemed to be validated, at least in part, by the firebombing of Japanese cities and the two atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Japan’s urban areas, composed largely of flammable wood and paper structures, proved extremely vulnerable to incendiary raids, and its dispersed cottage industries were wiped out or crippled. Air raids on Japan played a major role in ending its capacity to sustain the war.

The case of Germany was more complex. Despite a sustained and increasingly destructive Allied bombing campaign against German cities, oil facilities, and transport networks, German industrial output actually increased for much of the war, thanks in part to reorganization, dispersal of production, and ruthless mobilization of resources. Strategic bombing did eventually contribute to the collapse of the German war effort, especially when oil production and rail networks were heavily targeted, but it did not quickly or decisively win the war on its own.

Within Germany, the Luftwaffe’s doctrine focused primarily on supporting the army through close air support and battlefield interdiction, not on long-range strategic bombing. As a result, the Luftwaffe never developed a truly successful heavy bomber fleet. The leading advocate of strategic bombing within the Luftwaffe, Chief of Staff General Walther Wever, died in an air crash in 1936, ironically on the day that specifications for the so-called Ural bomber were published. This project, eventually leading to the Heinkel He 177, aimed to produce a bomber capable of striking deep into the Soviet Union. In practice, the He 177 suffered from severe technical problems and saw limited use against the Soviet Union and England. After Wever’s death, development director Ernst Udet steered German air policy toward dive bombers and tactical aircraft, leaving Germany without the dedicated heavy bombers that Britain and the United States would later field.

World War II: the high point of piston-engined heavy bombers

When Britain and France declared war on Germany in September 1939, the Royal Air Force (RAF) actually lacked a modern, four-engined heavy bomber in operational service. Designs such as the Handley Page Halifax and Avro Lancaster were originally conceived as twin-engined bombers, but as demands for greater payload and range grew—and as technical problems with the ambitious Rolls-Royce Vulture engine became apparent—they were redesigned around four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. The Halifax reached front-line squadrons in November 1940 and flew its first raid against Le Havre on the night of 11–12 March 1941. Typical British heavy bombers of this period carried several power-operated gun turrets, often three, mounting a total of around eight machine guns for defense.

Another early British heavy bomber, the Short Stirling, reached squadrons in January 1941. It was developed from the successful Short Sunderland flying boat and used the same Bristol Hercules radial engines, as well as a similar wing, cockpit, and upper fuselage layout. The boat hull was replaced by a conventional lower fuselage, and the result was a hefty bomber able to carry up to 14,000 lb (6,400 kg) of bombs—nearly twice the typical load of the American B-17 Flying Fortress—though only over a combat radius of about 300 miles (480 km). The Stirling’s short, thick wing allowed a surprisingly tight turning circle, letting it out-turn main German night fighters such as the Messerschmitt Bf 110 and Junkers Ju 88. However, the same wing limited the aircraft’s ceiling to around 12,000 ft (3,700 m), making it more vulnerable to flak and fighters. Within five months of its introduction, 67 of the 84 Stirlings in service had been lost, underlining the brutal attrition rates faced by early heavy bomber crews.

Because Britain had few heavy bombers early in the war, the United States lent 20 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses to the RAF. In July 1941, the RAF began daylight raids using these aircraft against warships and port facilities at Wilhelmshaven and Brest. The lessons were harsh. The B-17C variant then in service proved unreliable in this environment, with engine failures, maintenance issues, and insufficient defensive armament. Eight aircraft were lost to combat or breakdown in just a few raids, and by September 1941 the RAF abandoned daylight bombing with the B-17. It was clear that the early Fortress models were not yet ready for sustained high-intensity operations.

Feedback from combat quickly found its way back to Boeing’s engineers. When the improved B-17E model began flying from British bases in July 1942, it incorporated many additional defensive gun positions, including a crucial tail gunner station. Over time, U.S. heavy bomber designs were optimized for formation flying, with overlapping fields of fire. Mature B-17 models carried ten or more machine guns (and sometimes cannons) in powered turrets and flexible mounts. Guns were positioned in tail turrets, nose and cheek positions, dorsal (top) turrets, ventral (belly) turrets, and waist gun stations along the fuselage. The B-17G eventually carried thirteen .50-caliber machine guns, creating formidable firepower against attackers. To coordinate and assemble large formations, dedicated “assembly ships” painted in high-visibility patterns were used to guide bombers into their combat boxes before each mission.

Even with all this armament—adding roughly 20% to the empty weight and demanding more powerful versions of the Wright Cyclone engines—daylight raids remained costly when bombers lacked fighter escort. The RAF’s own interceptors, such as the Supermarine Spitfire, had limited range and could not accompany bombers deep into occupied Europe. A relatively short raid against the Rouen-Sotteville rail yards on 17 August 1942 required four Spitfire squadrons to cover the outbound leg and five more to protect the return.

The U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) made aircraft factories and component plants a priority, hoping to cripple German production directly. On 17 August 1943, 230 B-17s attacked the ball-bearing works at Schweinfurt, returning in October with a second raid involving 291 bombers. Although the plant was heavily damaged, the cost was enormous: 36 Fortresses lost on the first mission and 77 on the second. A total of around 850 airmen were killed or captured, and only 33 aircraft came back from the October raid without damage. These losses hinted at the limits of unescorted daylight precision bombing.

The picture changed somewhat with the arrival of long-range escort fighters and drop tanks. North American P-51 Mustangs and extended-range Republic P-47 Thunderbolts could now accompany bombers as far as their deepest targets. During “Big Week” (20–25 February 1944), a sustained offensive against German aircraft production, bombers flew about 3,500 sorties with fighter escort. Losses remained serious—around 247 aircraft—but the campaign significantly weakened the Luftwaffe and was considered acceptable at the time.

Other U.S. heavy bombers, such as the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, pushed defensive technology further by mounting Sperry ball turrets. These rotating spheres under the fuselage provided a 360-degree horizontal field of fire and around 90 degrees of vertical elevation, using twin M2 Browning .50-caliber machine guns effective out to about 1,000 yards (910 m). The B-24 itself emerged from a proposal for Consolidated to build B-17s under license; instead, the company offered a new design with longer range, higher speed, and greater altitude performance, plus an extra ton of bombs. Early orders went to France and Britain, with only a small batch for the USAAF. Eventually, the Liberator became one of the most widely built American bombers of the war.

At first, neither the USAAF nor the RAF considered the B-24 ideal for strategic bombing over heavily defended targets. It was used in roles such as VIP transport and maritime patrol, where its long range was an asset. That long range also made it suitable for daring missions, like the 1 August 1943 raid of Operation Tidal Wave, in which 177 Liberators took off from Benghazi, Libya, to attack Romanian oil refineries around Ploiești. Navigational errors, strong flak, and fighter interception meant that only about half returned to base; some landed in Cyprus or neutral Turkey, where they were interned, and just 33 aircraft were undamaged. Damage to the refineries was repaired relatively quickly, and oil production actually rose afterward, raising questions about the cost-effectiveness of such low-level, high-risk operations.

By October 1942, the new Ford Motor Company plant at Willow Run, Michigan, was assembling Liberators on a genuinely industrial scale. By 1944, production sometimes reached more than one aircraft per hour, helping the B-24 become the most produced American military aircraft of all time. The Liberator became the standard heavy bomber in the Pacific Theater for the USAAF and the primary heavy bomber of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The South African Air Force (SAAF) used Liberators for long-range special missions, such as dropping supplies into Warsaw during the 1944 uprising.

Parallel to the American developments, Britain turned the problematic Avro Manchester—a twin-engined bomber powered by the Rolls-Royce Vulture—into the highly successful Avro Lancaster. Vulture engine troubles made the Manchester underpowered and unreliable, prompting designers to stretch the wings, fit four Merlin engines, and refine the airframe. The redesign reached squadrons in early 1942 as the Lancaster. With an undivided bomb bay running along the fuselage, the Lancaster could carry a standard load of 14,000 lb (6,400 kg) of bombs, and with special modifications, even larger “blockbuster” weapons such as the 12,000 lb “Tallboy” and 22,000 lb (10,000 kg) “Grand Slam.” The undivided bomb bay was a key feature that made these extraordinary loads possible.

The British engineer Barnes Wallis, deputy chief aircraft designer at Vickers, devoted much of his energy to designing special weapons intended to shorten the war. Observing how stones skipped across water, he conceived a “spherical bomb, surface torpedo” that would bounce across the surface of reservoirs or harbors. Two versions of this “bouncing bomb” were developed. The smaller “Highball” was aimed at warships and won crucial Admiralty funding; this 1,280 lb (580 kg) weapon, half of which consisted of a powerful explosive called Torpex, was designed to sink ships like the German battleship Tirpitz lying behind torpedo nets. Development delays meant Highball was never used against the Tirpitz; instead, two Tallboy bombs dropped from 25,000 ft (7,600 m) by Lancasters finally capsized the battleship in November 1944. The larger bouncing bomb, “Upkeep,” was famously used by 617 Squadron—the “Dambusters” under Wing Commander Guy Gibson—to breach the Möhne and Eder dams in May 1943, causing devastating flooding in Germany’s Ruhr industrial heartland.

In March and April 1945, as the war in Europe neared its end, Lancasters dropped Grand Slam and Tallboy bombs on U-boat pens and railway viaducts across northern Germany. At Bielefeld, more than 100 yards (about 91 m) of viaduct were destroyed, and the massive bombs created an “earthquake” effect that shattered foundations previously thought invulnerable.

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress represented a further leap in heavy bomber technology. A development of the B-17 concept but on a larger scale, it used four Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone engines, each providing far more power than earlier radial engines. This allowed the B-29 to fly higher, faster, and farther than previous heavy bombers, while also carrying a larger bomb load. It introduced features such as a pressurized cabin and remote-controlled defensive turrets. Four twin-gun turrets along the fuselage were controlled via an analog computing sighting system, with operators using sighting blisters rather than directly manning each gun. Only the tail gun was controlled manually by a dedicated gunner.

Early B-29 operations from bases in India and China faced daunting logistics, with fuel and supplies having to be ferried over the Himalayas (“the Hump”) to forward bases in China. These constraints limited sortie rates and made the campaign costly. The capture of islands such as Saipan in the Mariana chain allowed the U.S. to establish large air bases within range of the Japanese home islands, dramatically improving efficiency. Initially, high-altitude daylight raids with conventional high-explosive bombs were used, but these delivered disappointing results against dispersed, mostly wooden cities. The campaign then shifted to low-level nighttime incendiary attacks, which the B-29s had not originally been designed for but performed with devastating effect. Japan’s flammable urban construction meant entire districts could be burned out in a single raid.

On 6 August 1945, the B-29 Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb used in war on Hiroshima. Three days later, another B-29, Bockscar, dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki. These attacks, combined with the ongoing conventional and incendiary bombing campaign and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war, led Japan to announce its surrender on 15 August. The formal instrument of surrender was signed on 2 September 1945, aboard the battleship USS Missouri, bringing World War II to an end.

After World War II: the jet age and strategic deterrence

In the years immediately following World War II, terminology shifted. The label “strategic bomber” came into wide use to describe aircraft capable of carrying significant ordnance loads over long distances, deep behind enemy lines. These strategic bombers were complemented by smaller fighter-bombers and attack aircraft with shorter range and lighter bomb loads, used primarily for tactical strikes and battlefield support. Over time, terms such as “strike fighter,” “attack aircraft,” and “multirole combat aircraft” emerged for these smaller, flexible platforms, while heavy or strategic bombers remained focused on long-range, high-payload missions.

When North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950, the U.S. Air Force responded with daylight B-29 raids on transportation and supply lines. Superfortresses flew from bases in Japan under the United Nations banner, attempting to interdict railways, bridges, and supply depots. However, the main flow of supplies from the Soviet Union into North Korea lay beyond the political and practical reach of these bombers, and there were few classic “strategic” targets within North Korea itself. As a result, the heavy bombers were often used in an interdiction and close support role that did not fully exploit their strengths.

Initially, distance and basing limitations meant that fighter escorts could not accompany the B-29s all the way to their targets, leaving the bombers vulnerable. In November 1950, Soviet-built Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 jet fighters, often flown by Soviet pilots, began intercepting B-29s over North Korea. The MiG-15 had been designed with the destruction of Western heavy bombers in mind and could outperform any Allied fighter then in theater until more capable jets like the F-86 Sabre arrived in numbers. After 28 B-29s were lost, U.S. commanders restricted the bombers to night operations and focused them on destroying supply routes, including key bridges over the Yalu River into China.

By the 1960s, the role of heavy bombers in nuclear strategy had changed again. Intercontinental ballistic missiles offered near-instantaneous delivery of nuclear warheads, with no risk to aircrews, and were increasingly seen as the backbone of strategic deterrence. More accurate precision-guided munitions, as well as nuclear bombs and missiles small enough to be carried by fighter-bombers, allowed smaller aircraft to perform many missions that once required a large bomber.

Despite these developments, large strategic bombers such as the B-52 Stratofortress, the variable-geometry B-1B Lancer, and eventually the stealthy B-2 Spirit were retained and modernized. They found enduring roles in conventional conflicts, particularly where their ability to carry large payloads of both unguided and precision-guided munitions was invaluable. During the Vietnam War era, B-52s flew massive bombing campaigns such as Operation Menu, Operation Freedom Deal, and Operation Linebacker II, dropping hundreds of thousands of tons of bombs across Southeast Asia.

The Soviet Union followed a similar path, developing a family of heavy bombers including the turboprop-powered Tu-95 “Bear” and the supersonic swing-wing Tu-160 “Blackjack,” introduced in the late 1980s and often described as the heaviest and fastest bomber ever built. The Tu-160 can carry up to a dozen long-range cruise missiles and has been used in modern conflicts for stand-off strikes.

China, drawing on the Soviet Tu-16 design, developed the Xi’an H-6 series, which has evolved into a true long-range strategic bomber family. Modern variants such as the H-6K and H-6N feature new engines, glass cockpits, enhanced avionics, and the ability to carry advanced cruise missiles. They provide China with a long-range, stand-off strike capability that complements its ballistic missile forces and plays a central role in its regional deterrence posture.

In 2010, the New START treaty between the United States and Russia offered a more formal definition of a “heavy bomber” for arms control purposes. Under this agreement, a heavy bomber is generally defined as an aircraft with a range greater than about 8,000 kilometers (5,000 miles) and equipped to carry long-range nuclear air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs) that were tested or deployed after 1986. This legal definition reflects how, by the late 20th and early 21st centuries, heavy bombers were viewed primarily as part of nuclear deterrence and strategic arms agreements rather than just large conventional bomb carriers.

Looking ahead, the heavy bomber concept continues to evolve. The U.S. Air Force’s B-21 Raider, a next-generation stealth bomber designed by Northrop Grumman, made its first flight in 2023 and is expected to enter service later in the 2020s as older bombers are gradually retired. Russia is working on the Tupolev PAK DA, a planned subsonic, stealthy flying-wing bomber intended to eventually supplement or replace older designs such as the Tu-95 and Tu-160. In all of these programs, the themes are similar: stealth to penetrate modern air defenses, long range, flexibility to carry both nuclear and conventional weapons, and extensive integration with satellite, cyber, and electronic warfare networks.

World War I heavy bomber list

The following aircraft represent some of the notable heavy bomber designs of World War I. Each type reflects a different national approach to long-range bombing at a time when the very idea of strategic airpower was still experimental:

-

Caproni Ca.4 (Italy) – A multi-engined Italian heavy bomber family, the Ca.4 series used a distinctive three-boom layout and multiple engines arranged in push-pull configuration. These bombers were employed for long-range raids over the Alps and against Austro-Hungarian targets, demonstrating Italy’s early commitment to strategic bombing.

-

Caproni Ca.5 (Italy) – An evolution of the Caproni line, the Ca.5 featured more powerful engines and structural improvements. It served in the later stages of the war and into the immediate postwar period, carrying heavier bomb loads and offering better reliability than its predecessors.

-

Handley Page Type O (United Kingdom) – As discussed earlier, the Type O/100 and O/400 were key British heavy bombers designed for long-range raids over occupied Europe and naval bases. Their large wings and capacious bomb bays made them among the most capable Allied bombers of the war.

-

Handley Page V/1500 (United Kingdom) – The V/1500 was an even larger British bomber designed late in the war to carry out extremely long-range missions, including potential raids on Berlin from bases in Britain. Though it saw little wartime service, it showed just how ambitious heavy bomber projects had become by 1918.

-

Gotha G.IV (German Empire) – The G.IV represented one of Germany’s best-known heavy bombers, used in the famous Gotha raids on British cities. Its long range and relatively high altitude capability allowed it to cross the North Sea and strike London, making it a symbol of German strategic bombing.

-

Gotha G.V (German Empire) – A further development of the Gotha line, the G.V introduced refinements to structure and systems, but operational conditions and improving Allied defenses meant it did not enjoy the same impact as the earlier G.IV, even though it remained an important part of Germany’s bomber force.

-

Sikorsky Ilya Muromets (Russian Empire) – The pioneering Russian heavy bomber described earlier, notable for its four engines, enclosed crew compartments, and substantial defensive armament. It served on the Eastern Front and set standards for size and capability that would not be dwarfed for many years.

-

Vickers Vimy (United Kingdom) – A long-range heavy bomber that arrived too late to change the outcome of the war but went on to achieve legendary status in civil and record-breaking flights, most famously the first non-stop transatlantic crossing.

-

Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI (German Empire) – The most numerous of the giant Riesenflugzeug series, the R.VI operated in small numbers but symbolized German attempts to build truly colossal bombers. These aircraft carried large bomb loads over long distances, but their complexity, cost, and vulnerability limited their impact.

Interwar period (interbellum) heavy bombers

During the interwar years, air forces and manufacturers experimented with new heavy bomber designs, often combining lessons learned during World War I with advances in engines and airframes. Many of these aircraft were built in small numbers, but they laid the groundwork for the heavy bomber fleets of World War II:

-

Caproni Ca.90 (Italy) – One of the largest land-based aircraft of its time, the Ca.90 was a gigantic triplane bomber with multiple engines mounted in tandem. Although only a handful were built, it reflected Italy’s willingness to explore extreme size and power in pursuit of strategic air capabilities.

-

Farman F.220 (France) – A French four-engined bomber and transport, the F.220 family served in various roles including long-range reconnaissance and night bombing. Its twin-boom layout and high-mounted wing gave it a distinctive appearance and decent performance for the period.

-

Fairey Hendon (United Kingdom) – The Fairey Hendon was one of the RAF’s early monoplane bombers, featuring all-metal construction and a low wing. Though quickly overshadowed by newer designs, it marked a transition from biplane to monoplane heavy bombers in Britain.

-

Handley Page Heyford (United Kingdom) – A biplane heavy bomber that was one of the last of its breed, the Heyford served as a mainstay of the RAF in the early 1930s. Its unusual fuselage, suspended between the wings, and fixed undercarriage looked archaic by the late 1930s but embodied the cautious evolution of bomber design in that era.

-

Handley Page Hinaidi (United Kingdom) – An updated version of earlier Handley Page night bombers, the Hinaidi continued the biplane tradition with incremental improvements in engines and structure. It filled the gap between World War I types and more modern interwar bombers.

-

B-2 Condor (United States) – An American twin-engined bomber and observation platform, the B-2 Condor was built in small numbers but used for high-altitude flight experiments and long-range missions. It provided valuable experience in operating large aircraft at significant altitudes.

-

Junkers Ju 89 (Germany) – A German prototype for a long-range heavy bomber, part of the early “Ural bomber” concept. Although the Ju 89 did not enter mass production, it illustrated Germany’s intermittent interest in strategic bombing before priorities shifted toward tactical aircraft.

-

Mitsubishi Ki-20 (Japan) – A Japanese heavy bomber based on the German Junkers G.38 design, built under license. Only a few were produced, but they gave the Imperial Japanese Army experience with very large, multi-engined aircraft.

-

Tupolev TB-3 (Soviet Union) – A four-engined Soviet bomber with a thick, cantilever wing and fixed landing gear, the TB-3 was one of the first all-metal heavy bombers. It served not only as a bomber but also as a transport and even as a carrier for smaller fighter aircraft in “parasite” trials.

-

Petlyakov Pe-8 (Soviet Union) – The Pe-8 was the USSR’s only true four-engined heavy bomber to see service during World War II, but its development began in the late interwar period. It represented the Soviet attempt to field a long-range strategic bomber comparable to Western designs, though it was produced in small numbers.

World War II heavy bomber list

By World War II, heavy bomber design had matured, and many different nations fielded large, complex bombers tailored to their strategic doctrines:

-

Avro Lancaster (United Kingdom) – The RAF’s principal heavy bomber in the later war years, known for its versatility, large bomb bay, and ability to carry oversized weapons such as Tallboy and Grand Slam. It flew thousands of night raids over Europe and remains one of the most iconic bombers of all time.

-

Avro Manchester (United Kingdom) – The Manchester was the Lancaster’s troubled predecessor, powered by twin Rolls-Royce Vulture engines that proved unreliable. Its shortcomings pushed Avro to redesign the airframe with four Merlins, leading directly to the successful Lancaster.

-

Bloch MB.162 (France) – A French four-engined bomber prototype intended to deliver high speed and long range. The MB.162 program was cut short by the German invasion, but it showed that France was developing modern monoplane heavy bombers by the late 1930s.

-

B-17 Flying Fortress (United States) – The B-17 combined durability, extensive defensive armament, and the ability to sustain heavy damage and still return home. It became the symbol of American daylight strategic bombing over Europe and remains legendary for its resilience.

-

B-24 Liberator (United States) – With higher speed and longer range than the B-17, the Liberator was used in many theaters, from anti-submarine patrols over the Atlantic to long-range bombing in the Pacific. Its large, high-aspect-ratio wing gave it great endurance but made it more demanding to fly.

-

B-29 Superfortress (United States) – The most advanced heavy bomber of World War II, with pressurization, remote-controlled turrets, and powerful engines. It delivered both conventional and atomic bombing campaigns against Japan and foreshadowed the jet-age strategic bombers that followed.

-

Consolidated B-32 Dominator (United States) – Designed as an alternative to the B-29, the B-32 saw limited service late in the war. It featured different structural solutions and defensive arrangements but arrived too late to make a major impact.

-

Dornier Do 19 (Germany) – An early German four-engined bomber prototype intended as a strategic bomber. The project was canceled as the Luftwaffe prioritized twin-engined medium bombers and dive bombers, aligning with its tactical doctrine.

-

Dornier Do 317 (Germany) – A further development of Dornier’s bomber designs with improved performance and pressurization, the Do 317 remained at the prototype stage and did not become a standard heavy bomber.

-

Focke-Wulf Fw 200 (Germany) – Originally a long-range airliner, the Fw 200 “Condor” was adapted as a maritime patrol and bomber aircraft, used effectively over the Atlantic to shadow convoys and guide U-boat attacks, though it was not a classic high-altitude heavy bomber.

-

Handley Page Halifax (United Kingdom) – Alongside the Lancaster and Stirling, the Halifax formed part of the RAF’s trio of four-engined heavy bombers. It flew a wide variety of missions, including bombing, glider towing, and special operations.

-

Heinkel He 177 (Germany) – Intended as Germany’s main long-range heavy bomber, the He 177 was plagued by engine and reliability problems due to its complex two-engine “paired” configuration driving four propellers. Although it saw combat, it never fulfilled its original strategic ambitions.

-

Heinkel He 274 (Germany) – A high-altitude bomber derived from the He 177 lineage, largely completed in France and finished postwar for evaluation. It highlighted late-war German interest in high-altitude bombing, but never entered operational service.

-

Nakajima G8N (Japan) – A four-engined Japanese heavy bomber prototype designed for long-range missions. Allied bombing and Japan’s deteriorating war situation limited production, and the G8N did not see combat, but it represented Japan’s attempt to build a modern heavy bomber comparable to Allied types.

-

Petlyakov Pe-8 (Soviet Union) – The Pe-8 performed long-range bombing missions for the Soviet Air Force, including a famous diplomatic flight to the United States carrying Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov. Its production numbers remained small, but it was an important symbol of Soviet long-range aviation.

-

Piaggio P.108 (Italy) – Italy’s only four-engined heavy bomber to see operational service in World War II, the P.108 featured advanced features like remote-controlled gun turrets in the outer wings. It flew missions over the Mediterranean and was used for both bombing and transport roles.

-

Savoia-Marchetti SM.82 (Italy) – A versatile three-engined aircraft used as a bomber and long-range transport. Its ability to carry heavy loads over long distances made it useful for supplying distant theaters as well as for bombing missions.

-

Short Stirling (United Kingdom) – The RAF’s first four-engined heavy bomber, with strong take-off performance and maneuverability but limited ceiling. It was gradually shifted from main bombing duties to roles such as mine-laying and glider towing as newer bombers arrived.

-

XB-15 (United States) – An experimental long-range bomber built to explore the feasibility of extremely large aircraft. The XB-15 served mostly as a testbed and transport, but it influenced later designs by proving large-airframe concepts.

-

XB-19 (United States) – Even larger and more experimental than the XB-15, the XB-19 was a massive prototype that tested structural and aerodynamic ideas for very large bombers. Though never produced in quantity, it helped engineers understand the challenges of building and operating huge aircraft.

Cold War heavy bombers

During the Cold War, heavy and strategic bombers were central to nuclear deterrence strategies. Many new designs emerged, often featuring jet propulsion, swept wings, and eventually variable geometry or stealth:

-

Avro Lincoln (United Kingdom) – A development of the Lancaster with longer wings and more powerful engines, the Lincoln served as a stopgap heavy bomber for the RAF in the early Cold War, particularly in colonial conflicts, until the arrival of more advanced jet bombers.

-

Avro Vulcan (United Kingdom) – The Vulcan was one of the famous British “V-bombers,” a delta-winged strategic bomber designed to carry nuclear weapons at high altitude and high speed. Its striking silhouette and advanced aerodynamics made it one of the most distinctive bombers ever built.

-

Handley Page Victor (United Kingdom) – Another V-bomber, the Victor featured a crescent-shaped swept wing and futuristic lines. Initially used as a nuclear bomber, it later served primarily as an air-to-air refueling tanker, extending the life of the design well into the late 20th century.

-

Vickers Valiant (United Kingdom) – The first of the British V-bombers to enter service, the Valiant was relatively conservative in design but provided the RAF with a rapid path into the jet-powered strategic bomber era. It carried out Britain’s early nuclear weapons tests and operational deployments.

-

B-1 Lancer (United States) – A supersonic, variable-geometry bomber designed to penetrate heavily defended airspace at low altitude. Initially conceived as a high-speed nuclear bomber, the B-1B variant was later adapted to carry large loads of conventional precision weapons in post–Cold War conflicts.

-

B-36 Peacemaker (United States) – One of the largest combat aircraft ever built, the B-36 featured six pusher propellers and, in later versions, four jet engines for additional power. With extraordinary range, it was designed to reach targets deep within the Soviet Union from bases in North America.

-

B-58 Hustler (United States) – The first operational supersonic bomber, the B-58 used a slender delta wing and podded weapons underneath the fuselage. It was fast and technologically advanced, but also expensive and demanding to operate, leading to a relatively short service life.

-

B-47 Stratojet (United States) – A swept-wing, six-engined medium bomber that served as a key part of the U.S. nuclear deterrent in the 1950s. The B-47 helped establish many of the design principles that would later be refined in airliners and subsequent bombers.

-

B-50 Superfortress (United States) – A development of the B-29 with more powerful engines and structural improvements. The B-50 served in reconnaissance, refueling, and other support roles even after it was no longer front-line as a bomber.

-

B-52 Stratofortress (United States) – Introduced in the 1950s, the B-52 has become one of the longest-serving combat aircraft in history. With multiple upgrades, it continues to fly into the 21st century, carrying cruise missiles, smart bombs, and a variety of conventional and nuclear weapons.

-

Myasishchev M-4 (Soviet Union) – An early Soviet jet-powered strategic bomber with a straight wing, the M-4 was part of the USSR’s first attempts to field a jet bomber capable of reaching targets in North America. Its limited range and performance, however, meant it was soon overshadowed by newer designs.

-

Tupolev Tu-4 (Soviet Union) – A reverse-engineered copy of the American B-29, built from detailed examination of interned aircraft that had landed in Soviet territory during World War II. The Tu-4 allowed the USSR to quickly field a modern four-engined bomber and served as the basis for later developments.

-

Tupolev Tu-16 (Soviet Union) – A twin-jet medium bomber used extensively for both conventional and nuclear roles. Its basic design was exported or adapted widely, and it served as the starting point for China’s H-6 program.

-

Tupolev Tu-95 (Soviet Union) – A turboprop-powered strategic bomber with swept wings and distinctive contra-rotating propellers, the Tu-95 has remarkable range and speed for a propeller-driven aircraft. It remains in Russian service today, modernized and equipped with long-range cruise missiles.

-

Tupolev Tu-160 (Soviet Union) – A supersonic, variable-geometry strategic bomber with enormous payload capacity. Often described as the heaviest combat aircraft ever built, the Tu-160 combines speed, range, and firepower, and remains a central part of Russia’s long-range aviation forces.

Post–Cold War heavy bombers and future projects

In the post–Cold War era, heavy bombers have been used extensively in regional conflicts, often in conventional roles rather than purely nuclear ones. At the same time, new programs seek to keep the concept relevant in an age of sophisticated air defenses:

-

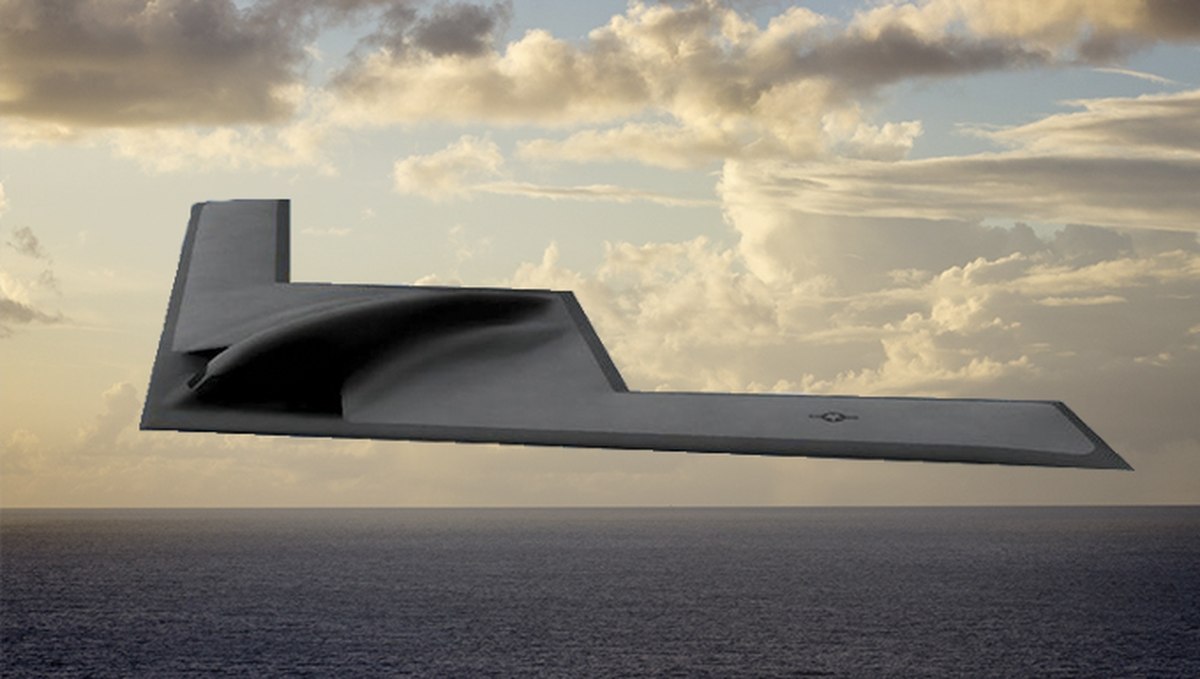

B-2 Spirit (United States) – A stealthy flying-wing bomber designed to penetrate advanced radar networks and deliver both nuclear and conventional weapons. Its low observable design, high endurance, and precision strike capability make it one of the most technologically advanced bombers ever built.

-

Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider (United States) – A new stealth bomber under development and testing, intended to complement and eventually replace older bombers such as the B-1B and portions of the B-2 and B-52 fleets. It emphasizes affordability, maintainability, and flexible payload options while remaining highly survivable.

-

Tupolev PAK DA (Russia) – A planned next-generation Russian stealth bomber, expected to be a subsonic flying-wing design optimized for long endurance, heavy payloads, and the use of modern stand-off weapons. Although still in development, it illustrates that Russia intends to preserve a strong bomber leg in its strategic forces.

In parallel, China continues to upgrade its H-6 fleet and is widely reported to be working on a future long-range stealth bomber that would complement or succeed the H-6 family, further reinforcing the idea that heavy or strategic bombers remain relevant for major powers.