Helicopters have a history that stretches far deeper than the first successful flight of a rotorcraft. Long before engineers understood aerodynamics, people watched spinning seeds fall through the air and wondered whether humans could imitate that effortless motion. The dream of vertical flight—lifting straight upward, hovering without forward movement, and gliding in any direction—captured the imagination of inventors for centuries. The road toward a practical helicopter was anything but simple; it developed through scattered insights, early failures, mechanical breakthroughs, and persistent experimentation across continents.

The earliest innovations weren’t aircraft at all but toys and natural observations. The sight of maple seeds spiraling to the ground or birds pausing in mid-air inspired some of humanity’s first ideas about rotary-wing flight. Over time, this fascination evolved into sketches, small mechanical models, and eventually full-scale experiments that began resembling the helicopters we know today. By the early 20th century, multiple inventors in Europe, Asia, and the United States were racing toward the same goal: building a machine that could rise vertically and hover with stability, something airplanes fundamentally cannot do.

As the decades unfolded, engineers refined rotor designs, experimented with new power sources, and learned from failures in ways that shaped the future of vertical lift. Autogiros bridged the gap between fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, and by the 1940s, the world finally saw machines capable of controlled vertical flight. War, technological competition, and expanding civilian applications pushed rotorcraft innovation further and faster.

What follows is a detailed journey through the major stages of helicopter development—from ancient concepts to the sophisticated machines operating around the globe today. Each era contributed vital ideas, and together they chart the evolution of one of humanity’s most versatile and transformative aviation technologies.

Early Roots

-

Nature provided the first lessons in rotary flight. Maple seeds spinning gently to the ground and hummingbirds hovering with remarkable precision led early observers to imagine how humans might replicate such motion mechanically. These natural phenomena served as inspiration long before scientific understanding existed.

-

Early evidence of rotary-wing concepts appears in ancient China around 400 BC, where simple bamboo flying tops demonstrated how spinning blades could create lift. Children played with these toys, but they quietly represented the earliest steps toward controlled vertical flight.

-

Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch of an “aerial screw” in 1483 offered one of the first conceptual drawings of a vertical lift device. Although the design was never built in his lifetime—and remained unpublished for centuries—it showed remarkable intuition about rotor-based ascent.

-

In the 1880s, American inventor Thomas Alva Edison experimented with small helicopter models. Much of his research focused on improving rotor blade efficiency and exploring lightweight power sources. Though his prototypes failed, Edison’s work highlighted the need for strong, lightweight materials and reliable engines.

-

Throughout the early 20th century, European engineers expanded the rotary-wing concept, laying crucial groundwork for the autogiro and the eventual helicopter. Their attempts introduced mechanical principles such as articulated rotors and control surfaces.

-

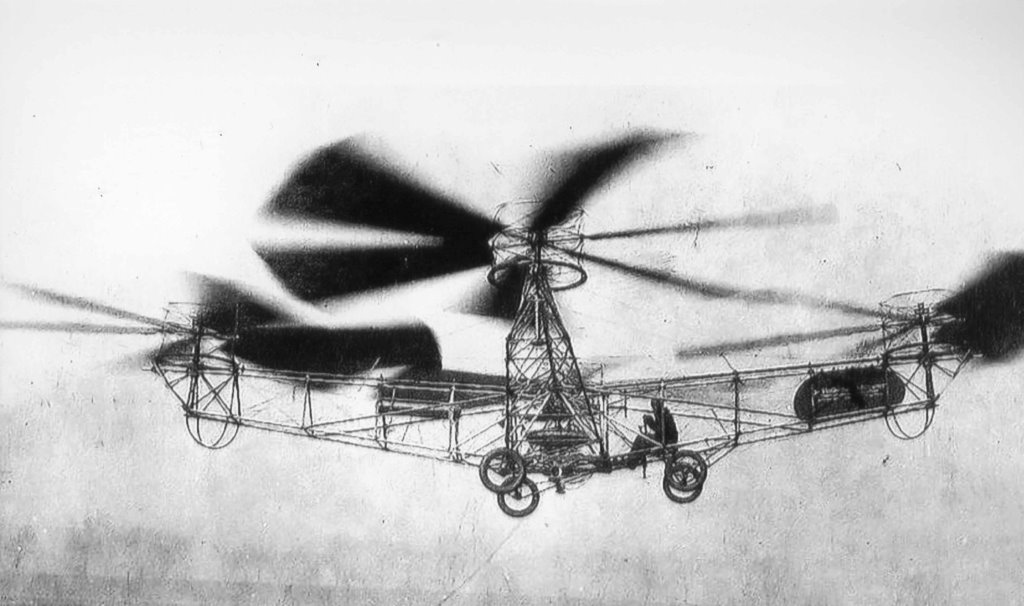

In 1907, just four years after the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk, two French teams—one led by Louis and Jacques Breguet and the other by Paul Cornu—tested experimental rotary-wing aircraft. Their machines lifted off briefly and inconsistently, revealing both the potential and the enormous engineering challenges ahead.

-

Around 1912 in Russia, Igor Sikorsky and Boris Yur’ev independently began designing vertical-lift aircraft. Both envisioned machines using a main rotor and a tail rotor—an arrangement that would later define modern helicopters—though their early creations lacked the power needed for sustained flight.

1920s

-

In 1923, Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva successfully built and flew the CA autogiro. This hybrid craft combined airplane-style wings with an unpowered rotor mounted above the fuselage. The rotor spun freely as air passed through it, providing lift while the engine pushed the aircraft forward. The autogiro proved stable and innovative, offering ideas that would eventually influence helicopter control systems.

-

In 1928, Harold Pitcairn ordered a Cierva C.8W autogiro, leading to the first U.S. flight of a rotating-wing aircraft on December 18 of that year. Pitcairn later licensed Cierva’s patents and established manufacturing in the United States, based at what would become the Willow Grove Naval Air Station. Under his leadership, American autogiro development accelerated, and aviator Amelia Earhart famously set an altitude record in a Pitcairn autogiro, drawing public attention to the aircraft’s potential.

-

In the Soviet Union, Nikolay Kamov designed the first Soviet autogyro, the KASKR-1. His early work paved the way for Kamov becoming the USSR’s primary helicopter manufacturer, widely known for coaxial rotor designs in later decades.

1930s

-

By the early 1930s, autogiros were widely used in multiple countries. They delivered mail, supported sightseeing operations, and served as experimental platforms for future vertical-lift innovations. In 1930, Harold Pitcairn received the prestigious Collier Trophy for advancing rotary-wing flight, marking the autogiro’s importance in aviation history.

-

Autogiros even made their way into extreme environments. A Kellett K-3 autogyro accompanied Rear Admiral Richard Byrd’s 1934 Antarctic expedition, offering valuable experience in challenging conditions.

-

Meanwhile, the first practical helicopter arrived in 1937. The German-built Focke-Achgelis FA-61 used a side-by-side twin-rotor configuration and demonstrated controlled vertical flight at a level previously unseen. Test pilot Hanna Reitsch famously flew it inside Berlin’s Deutschlandhalle in 1938, proving the helicopter’s ability to operate safely in confined spaces.

1940s

-

In 1940, the U.S. Congress passed the Dorsey-Logan Act, allocating funds to develop rotary-wing aircraft for military purposes. The onset of World War II highlighted the need for aircraft capable of rescuing personnel, conducting reconnaissance, and accessing locations unreachable by fixed-wing planes.

-

Igor Sikorsky achieved a major breakthrough in 1940 when he flew the VS-300, the first successful U.S. helicopter and the first to use the now-standard configuration of a main rotor and tail rotor. His design became the foundation for nearly all future helicopters. The Sikorsky R-4, developed shortly after, entered full production and demonstrated the value of helicopters during wartime, performing rescue missions in remote areas like Burma and Alaska.

-

Platt-LePage in Pennsylvania received a contract in 1940 to build a U.S. Army helicopter modeled after a German design. However, their XR-1 prototype suffered from stability and control issues, leading to the cancellation of the program.

-

In 1943, Frank Piasecki flew his PV-2 helicopter in Philadelphia. He later became the first FAA-certified helicopter pilot and went on to design successful tandem-rotor helicopters. His company, Piasecki Helicopter, eventually evolved into Boeing’s modern vertical lift division. Around the same time, Arthur Young built and flew the Bell Model 30, which would lead to the establishment of Bell Helicopter.

-

In Britain, Westland Aircraft began producing Sikorsky helicopters under license after World War II. Through a series of mergers, it later became Westland Helicopters, a major supplier of military rotorcraft.

-

In Russia, Mikhail Mil founded the Mil design bureau with the Mi-1 helicopter, initiating a long line of influential Soviet and Russian rotorcraft.

1950s

-

The Korean War demonstrated conclusively that helicopters could transform military operations. They allowed rapid evacuation of wounded soldiers, delivered ammunition and supplies to difficult terrain, and provided reconnaissance in areas where ground vehicles were impractical.

-

The Bell 47, purchased by the U.S. Army and designated OH-13, became iconic for its bubble canopy and reliable performance. It served in roles ranging from artillery spotting to medical evacuation, often appearing in newsreels and later in popular culture.

-

The introduction of turbine engines marked a turning point. Charles Kaman’s pioneering use of a turbine engine revealed an extraordinary power-to-weight advantage—four times that of piston engines. This breakthrough revolutionized helicopter performance for decades to come.

-

The Sikorsky H-34 emerged as a versatile platform used for transport, anti-submarine warfare, search and rescue, and VIP missions. Its reliability made it a favorite among military and civilian operators.

1960s

-

The Vietnam War, sometimes referred to as the Helicopter War, fully displayed the helicopter’s capabilities across a spectrum of missions:

-

Troop transport

-

Gunship support

-

Search and rescue and medical evacuation

-

Aerial resupply

-

Command and control coordination

-

-

During this era, several iconic helicopters entered service: the Bell UH-1 “Huey,” the world’s most recognized utility helicopter; the Bell AH-1 Cobra, the first dedicated helicopter gunship; and the Boeing CH-46 Sea Knight along with the powerful CH-47 Chinook. All played critical roles in battlefield mobility and support.

-

In the Soviet Union, the Mil Mi-8 began production and eventually became one of the most widely used helicopters in history, serving in military and civilian operations around the world.

1970s–Present

-

The lessons of Vietnam shaped a new generation of rotorcraft. The 1970s saw the development of the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter and the UH-60 Black Hawk utility helicopter, both of which became central to modern military aviation.

-

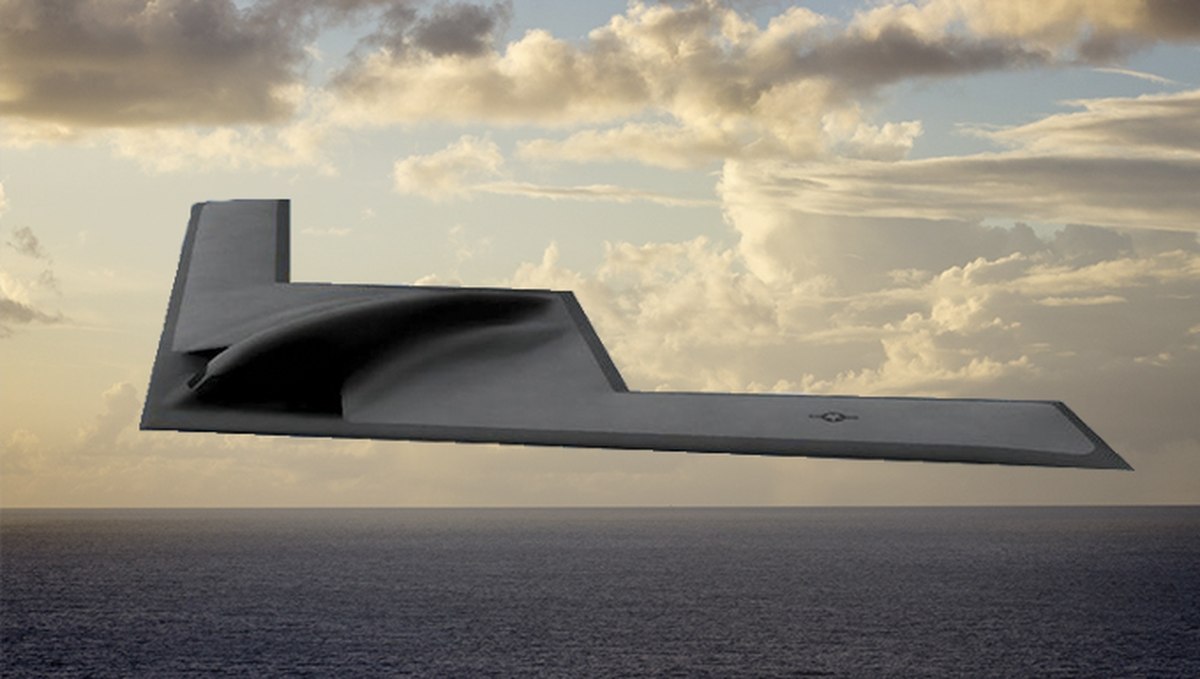

Bell and Boeing collaborated to create the V-22 Osprey, the first production tilt-rotor aircraft capable of vertical takeoff like a helicopter and high-speed forward flight like an airplane. Its unusual design opened new possibilities for long-range assault and transport missions.

-

The Sikorsky CH-53 Super Stallion emerged as one of the largest heavy-lift helicopters ever built, capable of moving massive cargo loads in demanding environments.

-

The Airbus UH-72 Lakota became the first U.S.-produced helicopter from a European-owned manufacturer, representing increasing international collaboration in rotorcraft development.

-

Civil aviation also benefited from advances in helicopter technology. The Sikorsky S-92 and Bell Jet Ranger became widely used for commercial transport, offshore operations, and corporate aviation.

-

Designer Frank Robinson introduced the R-22, a lightweight, affordable helicopter that became the most popular choice for pilot training and personal aviation worldwide.

-

European companies such as AgustaWestland and Airbus Helicopters established strong U.S. operations, contributing to global progress in helicopter manufacturing and innovation.

-

Today, tens of thousands of helicopters operate around the world, supporting:

-

Disaster relief

-

Medical evacuation

-

Firefighting

-

News reporting

-

Law enforcement

-

Construction and heavy lifting

-

Logging operations

-

Offshore oil rig transport

-

Executive and presidential travel

-

Military combat and support missions

-

-

These diverse uses show how rotorcraft have become essential tools for both civilian life and global security.

As helicopter technology continued to evolve through these decades, so did the expectations placed on rotorcraft. What began as simple experiments with spinning blades gradually transformed into a diverse family of aircraft capable of performing work that no other machine can match. Modern helicopters now combine digital avionics, composite materials, sophisticated engines, and advanced safety systems that early pioneers could scarcely imagine. Their roles span countless environments, from mountain ranges and open oceans to dense cities and remote conflict zones, each mission demanding a different combination of agility, endurance, lift, and precision.

What makes helicopter history especially compelling is how each breakthrough built on the last. The fragile autogiros of the 1920s taught engineers how to manage airflow over a freely turning rotor. The first stable helicopters of the 1940s proved that controlled vertical flight was not only possible but practical. Wartime deployments exposed new challenges and pushed designers to improve reliability, speed, and lifting power. Later generations added better engines, refined rotor hubs, and advanced flight controls, allowing helicopters to serve in rescue work, heavy construction, emergency medicine, and high-risk military operations. Even today, innovations continue to emerge as engineers explore hybrid propulsion, quieter rotor systems, unmanned platforms, and tilt-rotor designs that blur the boundary between airplane and helicopter.

Across all these developments, one theme remains constant: helicopters fill a role that no other aircraft can truly replace. Their ability to rise vertically, hover with precision, and maneuver in tight or inaccessible areas makes them indispensable for modern life. Whether delivering critical aid after disasters, transporting patients who cannot wait for conventional travel, supporting scientific expeditions, or shaping the outcomes of military missions, rotorcraft continue to influence the world in ways that stretch far beyond aviation.

The story of helicopters is still unfolding. Every new challenge, technological shift, or operational demand leads to refined designs and new capabilities. Understanding their history is not just about looking back—it offers insight into how future aircraft may evolve as engineers continue chasing the same dream that began with spinning seeds, early sketches, and those first bold experiments in vertical flight.