The question of whether Donald Trump would go to war with Iran can no longer be dismissed as speculative or rhetorical. In recent years, the Middle East has crossed several thresholds that once acted as brakes on escalation. Direct strikes, open retaliation, and short but intense confrontations between state actors have replaced the old pattern of quiet proxy conflicts and deniable operations. The brief but violent clash between Israel and Iran, followed by direct U.S. involvement, fundamentally altered assumptions about how far regional conflicts can go before Washington is pulled in.

For decades, analysts described U.S.–Iran tensions as a cold conflict defined by sanctions, covert action, cyber operations, and proxy warfare. That framework is now outdated. The region has entered a phase where red lines are thinner, response times are shorter, and miscalculation carries a much higher price. When missiles fly openly and nuclear facilities are discussed as legitimate targets in mainstream political discourse, the distance between crisis and war shrinks dramatically.

Donald Trump’s role in this environment is especially controversial. He is neither a traditional interventionist nor a conventional isolationist. His record shows a preference for shock actions, maximum pressure, and symbolic demonstrations of strength, combined with a deep reluctance to commit U.S. ground forces to long, grinding wars. This contradiction makes predicting his behavior difficult—and dangerous—because limited actions taken for deterrence can quickly spiral into larger confrontations once retaliation begins.

Iran, meanwhile, has adapted to decades of pressure by building a layered response strategy. It may avoid full-scale war, but it has proven willing to absorb strikes, retaliate asymmetrically, and test adversaries’ thresholds. Israel’s increasingly assertive posture toward Iran adds another destabilizing variable. Israeli leaders have made clear that they are prepared to act militarily when they believe existential red lines are being crossed, regardless of international hesitation. That reality places the United States in a position where it may not choose war—but may still be forced into it.

This article does not assume that Trump wants a war with Iran. Instead, it examines whether current realities make such a conflict more likely than many people are willing to admit. It looks at how recent regional clashes changed escalation dynamics, how U.S. decision-making is shaped by Israel’s actions, how Iran calculates risk after open confrontation, and what kinds of events could push a future Trump administration from pressure into direct conflict.

The real question is no longer “Would Trump start a war with Iran?”

It is whether the political, military, and regional conditions now make avoiding one far harder than it used to be.

What changed after the 12-day war

Before June 2025, a common assumption in Washington was that the U.S. and Iran would keep their conflict mostly indirect—sanctions, cyber, proxies, occasional skirmishes. Then Israel launched major strikes on Iran, Iran responded with missile and drone attacks, and the U.S. entered directly with strikes on three Iranian nuclear sites (per U.S. and multiple reporting).

That matters for the next few years for three reasons:

-

Thresholds moved

Once the U.S. has already struck Iranian nuclear facilities in this cycle, the psychological and political barrier to doing it again is lower than it used to be. -

Israel’s posture hardened

Israeli leaders framed the 12-day conflict as a historic outcome and signaled they intend to keep acting if Iran rebuilds capabilities. That increases the odds of repeat crisis moments. -

“Ceasefire” doesn’t equal “stable”

A ceasefire can stop shooting without solving anything underneath—deterrence questions, rebuilding, red lines, and revenge logic. European analysts have warned the post-war pause is fragile without strong de-escalation mechanisms.

What Trump is likely to do first: pressure, then controlled strikes

If Trump concludes Iran is rebuilding nuclear capacity faster than expected, or if Israel presents new intelligence pointing to a near-term breakout risk, the most likely Trump-style response is not an invasion. It’s a mixture of:

-

coercive diplomacy (demands + deadlines)

-

heavy sanctions and secondary sanctions

-

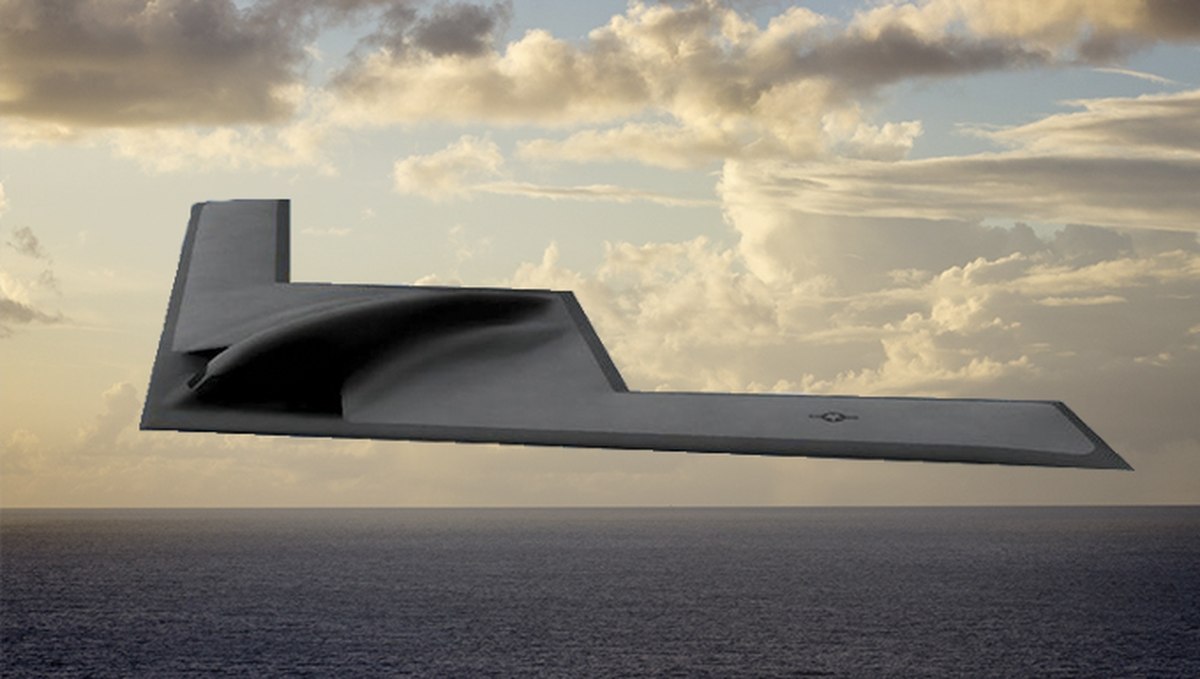

military positioning (carrier groups, air defense surges, B-2/B-52 messaging)

-

limited strikes meant to “restore deterrence”

That last part is the danger zone. Trump has shown he’s willing to use force as a demonstration move. And in June 2025, U.S. strikes on Iranian nuclear sites were widely described as a major escalation and a high-risk gamble.

So the realistic “war” question becomes: would he authorize another round of strikes if he believed the alternative was Iran getting closer to a bomb? Based on official messaging that Iran must not have a nuclear weapon, the answer is: it’s plausible.

The Israel factor (and why it can pull the U.S. in)

You specifically told me to consider Israel, and you’re right: Israel is the key accelerant.

Even if Trump prefers a controlled, limited confrontation, Israel may act on timelines that are shorter and less patient. If Israel strikes Iran again—especially nuclear-related targets—Tehran’s retaliation options often include U.S. assets in the region, whether directly or via aligned groups. That can force Trump into a choice: absorb the hit and de-escalate, or respond hard and risk a spiral.

The June 2025 sequence also shows a political pattern: Israel praised U.S. involvement, and the U.S. role became central in the conflict’s endgame and messaging.

What would actually trigger a bigger war in the next few years

Here are the most believable escalation paths—not speculation, but “if X happens, the incentives shift” logic:

A direct strike cycle around nuclear infrastructure

If Iran’s nuclear program is assessed as recovering faster than expected, Washington (or Israel) could strike again. Iran could respond with missile attacks on regional U.S. bases (as it has threatened in the past), and the U.S. could escalate to broader air campaigns.

A mass-casualty event involving U.S. forces

If a proxy attack (or misattributed attack) kills a large number of U.S. personnel, domestic pressure to retaliate sharply becomes intense, especially under a “strength” presidency.

A Strait of Hormuz shipping shock

Reuters has reported that Iranian officials have floated “all options” after U.S. strikes and that markets react sharply to the risk of energy disruption. If shipping is hit hard, Washington’s threshold for large military action drops fast.

A Lebanon/Hezbollah flare-up becoming regional

Israel–Hezbollah tensions remain a live fault line, and broader escalation can pull in Iran-linked networks and trigger U.S. involvement.

What makes full-scale war less likely

Even with all that, a long war is still constrained by reality:

-

Iran is not an easy target set. It can retaliate across multiple theaters and pressure the global economy.

-

U.S. public tolerance for another major Middle East war is limited.

-

Military planners know escalation control is harder than it looks once missiles are flying.

That’s why the “most probable” future is an unstable middle: recurring crises, occasional strikes, and proxy pressure—rather than a declared, multi-year ground war.

How to tell if it’s getting closer (practical indicators)

If you want to judge risk in real time over the next months/years, watch for these:

-

U.S. evacuation notices for dependents and non-essential staff across the Gulf

-

rapid deployment of additional Patriot/THAAD air defense batteries

-

unusual bomber task force movements and tanker build-ups

-

clear Israeli public messaging about “preventing reconstitution”

-

U.S. statements shifting from “deterrence” language to “denial” language (meaning: not just punishing Iran, but preventing capabilities)

When several of these line up at once, the odds of strikes rise sharply.

So… would Trump go to war with Iran?

If “war” means a planned invasion: unlikely.

If “war” means a renewed strike campaign that turns into an escalatory exchange: possible—and the June 2025 12-day conflict proves the region can reach that point faster than most people expect.

And the biggest driver is still the same: the nuclear question, plus Israel’s willingness to act first, and Iran’s ability to retaliate in ways that drag the U.S. into the next round.