Nearly everyone has heard the word “drone” by now. It has become the go-to label for those usually small, helicopter-like flying machines that people fly for fun, photography, inspections, and countless other tasks. Millions of them are in the air across the world, from quiet suburban parks to construction sites and remote landscapes. Still, despite how common the word has become, it’s far from the only term used to describe these aircraft, and that’s where confusion often begins.

It does feel a little odd when you stop and think about it. The same word is used for a lightweight plastic aircraft that might cost less than a family dinner, while also being applied to a highly advanced, multi-million-dollar military platform designed for surveillance or combat. Those machines live in completely different worlds and serve very different purposes. Naturally, that raises a fair question: if they’re so different, why are they often called the same thing?

Okay, let’s start with an idea that clears up part of the confusion right away. In simple terms, almost every UAV can be called a drone, but not every drone neatly fits the definition of a UAV. If that sounds circular or frustrating, you’re not alone—this overlap is exactly why the terminology trips so many people up.

Before digging deeper, it’s worth mentioning that these definitions are not frozen in stone. As unmanned aircraft continue to spread into new industries, regulators like the FAA will likely refine and standardize the language. That process takes time, but it’s necessary. Right now, “drone” is such a broad label that professionals in aviation, defense, mapping, and logistics don’t always agree on what it should include. Until clearer standards arrive, here’s a practical breakdown of the most common terms you’ll hear and how they differ from one another in everyday use.

Drone

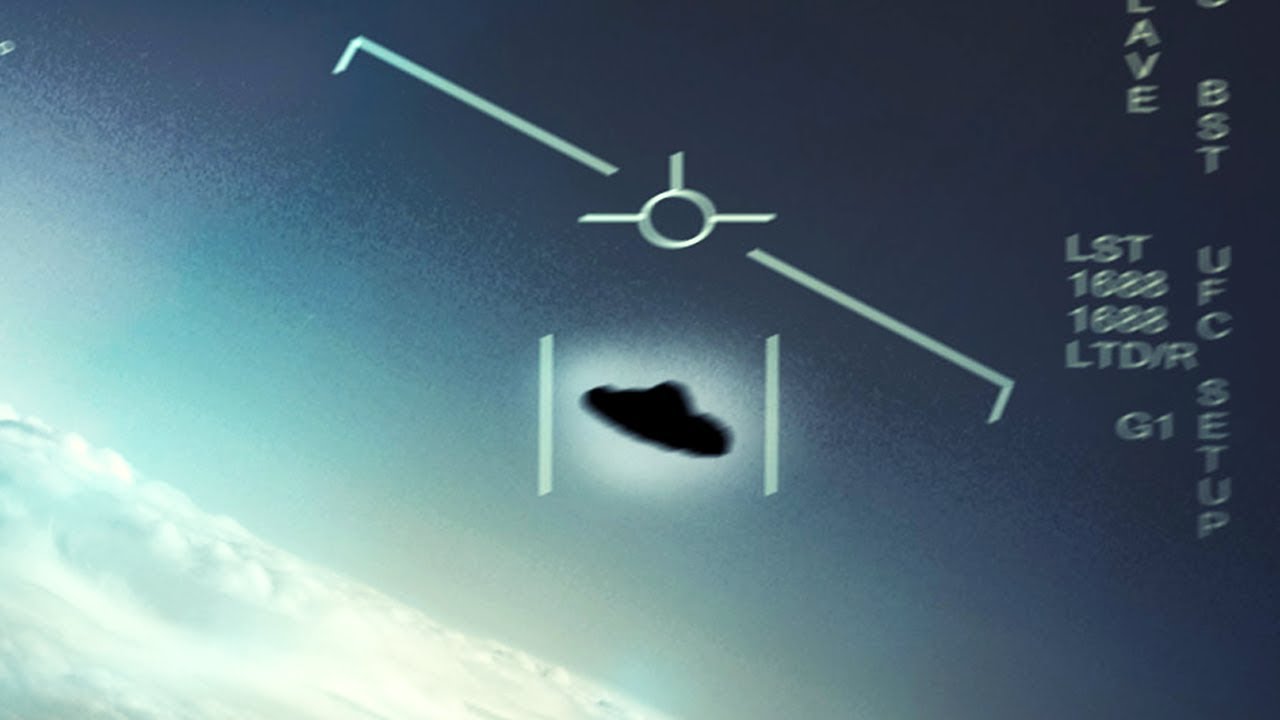

When most people hear the word drone, they picture an unmanned aircraft capable of flying without a pilot on board, sometimes even without constant human input. That definition aligns closely with how organizations like Scientific American describe it. In practice, though, the term is far broader than many realize.

A drone does not have to fly at all. The word can apply to autonomous or remotely controlled vehicles operating on land or at sea as well. Robotic submarines, ground robots, and other self-guided machines technically fall under the same umbrella. What ties them together is not the environment they operate in, but the absence of a human physically inside the vehicle.

That said, common usage has narrowed the meaning in everyday conversation. Most of the time, when someone says “drone,” they’re referring to an aircraft that can be flown remotely or programmed to follow a set path on its own. Beyond that, agreement becomes harder to find. Ask ten experts for a strict definition and you’ll likely hear ten slightly different answers, with the only shared point being that the aircraft has no onboard pilot.

There’s also a bit of history behind the word that many people find surprising. The term drone traces back to the de Havilland DH82B “Queen Bee,” a remotely controlled aircraft developed decades ago. That name, and the buzzing sound associated with it, stuck. Long before consumer quadcopters existed, the language was already being shaped by early experiments in unmanned flight.

UAV

UAV stands for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, and at first glance it seems like a more formal way of saying drone. In many situations, that’s exactly how it’s used. A UAV can be flown remotely using a controller, computer, or tablet, or it can operate autonomously using onboard systems. In everyday speech, people often swap “drone” and “UAV” without thinking twice, and usually no one minds.

The reason drone feels more common today has a lot to do with pop culture. Movies, television, news coverage, and social media have all embraced the word, giving it an edge in public recognition. Say “UAV” at a party and you might get a blank stare; say “drone” and everyone knows what you mean.

Within professional circles, however, the distinction becomes more nuanced. Some experts argue that a UAV should be capable of autonomous flight, not just basic remote control. Under that stricter interpretation, a simple toy quadcopter might be called a drone but wouldn’t fully qualify as a UAV. Using that logic, all UAVs could be considered drones, but not all drones would meet the technical bar to be called UAVs.

At the moment, there’s no universal agreement enforcing that separation. For most practical purposes, using whichever term feels more natural is perfectly acceptable, especially outside highly technical or regulatory discussions.

UAS

UAS stands for Unmanned Aircraft System, and this term tends to cause far less debate. Unlike drone or UAV, UAS does not describe just the flying machine itself. Instead, it refers to the entire operational setup required to make unmanned flight possible.

A UAS includes the aircraft, the control station on the ground, the communication links between them, and the human operator overseeing the mission. In other words, the UAV or drone is only one component within a much larger system. This perspective is especially useful in commercial and regulatory environments, where responsibility, safety, and control extend beyond the aircraft alone.

By using the term UAS, professionals can clearly distinguish between the physical vehicle and the broader framework that supports it. That clarity matters when discussing licensing, compliance, airspace management, and system reliability. It also explains why regulators often prefer UAS when drafting rules—it captures the full picture rather than focusing on just the aircraft.

RPA

RPA, short for Remotely Piloted Aircraft, is a term favored by many experienced pilots, particularly those involved with advanced or large-scale unmanned aircraft. The preference comes from a desire to emphasize skill and responsibility rather than automation alone.

Flying certain unmanned aircraft is nothing like operating a consumer drone from a park bench. These systems often require years of training, deep technical knowledge, and constant attention. The control stations used for aircraft such as the Global Hawk resemble the cockpit of a commercial airliner more than a handheld controller. Multiscreen displays, complex instrumentation, and coordinated teams are the norm.

The term RPA highlights the fact that a human pilot is actively involved, even if they’re located far from the aircraft itself. It pushes back against the casual image some people associate with drones and underscores the seriousness of these operations. Despite that distinction, RPA is still often treated as interchangeable with UAV, mainly because no single authority has settled on a definitive boundary between the terms.

As unmanned aviation continues to evolve, so will the language surrounding it. New roles, technologies, and regulations will shape how these aircraft are described. For now, understanding the intent behind each term—whether it focuses on autonomy, systems, or pilot involvement—goes a long way toward making sense of the conversation.