Food has always been one of the most powerful forces shaping human civilization, yet it is often treated as a background detail in history rather than a driving engine of change. In the ancient world, food determined where people settled, how societies were organized, which gods were worshipped, and even how wars were fought. Long before modern nutrition science or industrial farming, ancient peoples developed food systems that were deeply intelligent, carefully balanced, and tightly connected to the natural world around them.

Every ancient diet was the result of countless generations of trial and error. People learned which plants could be eaten safely, which animals could be domesticated, how to preserve food through harsh winters or long droughts, and how to manage land without exhausting it. Meals reflected climate, geography, trade networks, social class, and belief systems. What someone ate in ancient times could reveal their status, profession, region, and even their spiritual identity.

Ancient food systems were not simple or static. They evolved alongside technology, population growth, and cultural exchange. Irrigation canals reshaped landscapes, storage granaries shifted political power, and long-distance trade introduced new flavors and ideas. Food connected farmers to rulers, temples to markets, and families to the rhythms of the seasons.

By exploring ancient diets and food systems, we gain more than a list of ingredients or recipes. We uncover how early societies understood health, sustainability, and survival. We see how food created community, reinforced hierarchy, and preserved knowledge across generations. In many ways, the story of ancient civilization is the story of how humans learned to eat, adapt, and thrive in an unpredictable world.

The Foundations of Ancient Food Systems

At the core of every ancient food system was geography. What people ate depended first on where they lived.

River valleys supported grain-based diets. Coastal regions relied heavily on fish and seafood. Forested areas produced nuts, fruits, wild game, and honey. Deserts demanded ingenuity, preservation, and strict control over resources. Mountains created diets rich in dairy, hardy grains, and preserved foods.

Early food systems were local by necessity. Most people ate what they could grow, hunt, gather, or trade nearby. Long-distance trade existed, but it was expensive and reserved for luxury goods like spices, wine, or rare fruits.

Food systems were also seasonal. Ancient people ate differently throughout the year, adjusting to harvest cycles and weather patterns. Fresh produce appeared briefly, followed by long periods where dried, salted, smoked, or fermented foods dominated daily meals.

This seasonal rhythm shaped work schedules, religious festivals, and even social hierarchies.

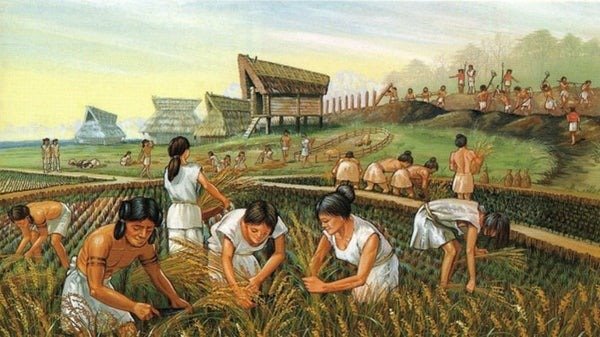

Agriculture and the Rise of Staple Crops

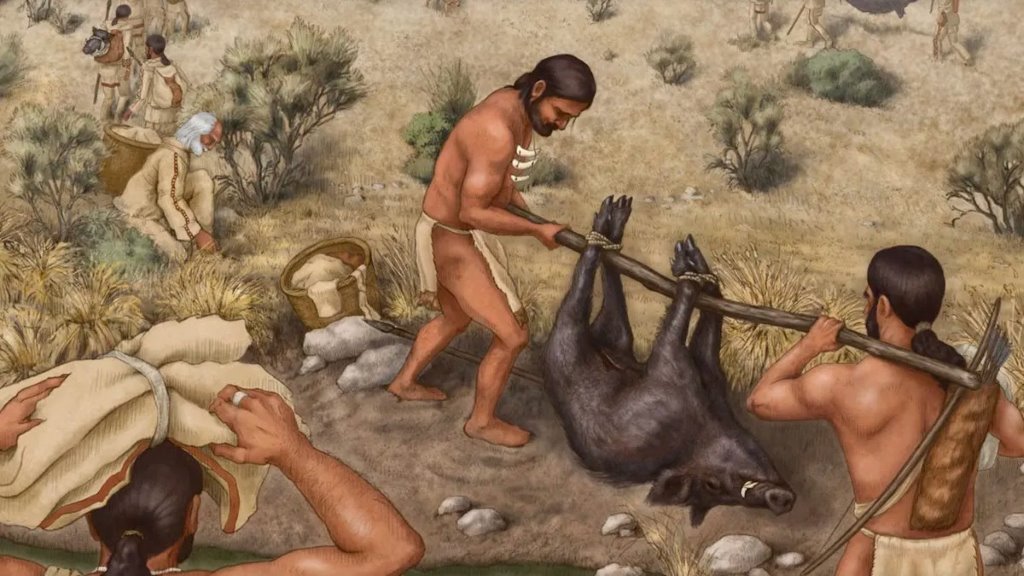

The shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture changed human diets forever.

Ancient societies domesticated crops that could be stored, transported, and grown in large quantities. These staple foods became the backbone of civilizations.

Grains were especially important. Wheat and barley dominated the Middle East and Mediterranean. Rice became central in East and South Asia. Millet and sorghum thrived in Africa. Maize transformed diets in the Americas. These crops were calorie-dense, relatively easy to grow, and adaptable to different conditions.

Staple crops allowed populations to grow, cities to form, and social classes to emerge. They also made societies vulnerable. Crop failure meant famine, unrest, and sometimes collapse.

Despite this risk, ancient farmers developed techniques to protect food supplies. Crop rotation, irrigation, terracing, seed selection, and storage systems all evolved to stabilize food production over time.

Animal Foods: Meat, Dairy, and Beyond

Animal products played a varied role in ancient diets, depending on culture and environment.

In many societies, meat was not eaten daily. It was expensive, required resources, and often carried religious or social significance. Meat consumption was common during festivals, rituals, or special occasions rather than as a daily staple.

Domesticated animals provided more than just meat. Milk, cheese, yogurt, butter, eggs, wool, leather, and labor were often more valuable over the long term. Dairy products were especially important in pastoral societies and mountainous regions where crops were limited.

Fishing was a major food source for river and coastal civilizations. Fish could be dried, salted, or fermented, making it a reliable protein source year-round.

Hunting supplemented diets with wild game, birds, and insects. In some cultures, insects were prized for their protein and fat content, a practice still common in many parts of the world today.

Foraging, Wild Foods, and Lost Knowledge

Even agricultural societies never fully abandoned foraging.

Wild plants, fruits, nuts, seeds, roots, and herbs added nutrition, flavor, and medicinal value to ancient diets. Many of these foods were seasonal delicacies or emergency resources during poor harvests.

Women often held the most knowledge about wild foods—knowing which plants were edible, when they ripened, and how to prepare them safely. This knowledge was crucial during famines or migrations.

Modern research suggests ancient diets were often more diverse than modern ones, including hundreds of plant species that are rarely eaten today. Much of this knowledge has been lost, replaced by reliance on a small number of global crops.

Food Preservation and Storage Techniques

Preservation was one of the most important skills in ancient food systems.

Without refrigeration, ancient societies developed sophisticated methods to extend the life of food. Drying, smoking, salting, pickling, fermenting, and storing in cool underground spaces were common techniques.

Grains were stored in sealed granaries. Meat and fish were dried or smoked. Fruits were sun-dried or turned into pastes. Milk became cheese or yogurt. Vegetables were fermented or pickled.

Fermentation deserves special attention. It improved shelf life, enhanced flavor, and increased nutritional value. Bread, beer, wine, cheese, yogurt, soy products, and fermented fish sauces were staples across many cultures.

Food storage was often centralized. Temples, palaces, or state granaries controlled reserves, giving political power to those who managed food supplies.

Social Class and What People Ate

Diet in the ancient world was deeply tied to social status.

Elites ate differently from common people. Wealthier households enjoyed more meat, refined grains, imported spices, sweeteners, and alcohol. Their meals were often elaborate, symbolic, and performative.

Common people relied on simpler foods: coarse bread, porridge, legumes, vegetables, and occasional animal products. These diets were often nutritionally balanced, even if monotonous.

Food inequality was visible and understood. What you ate signaled who you were in society. Feasts reinforced hierarchy, loyalty, and power.

Ironically, some elite diets were less healthy, relying heavily on refined foods and excess alcohol, while common diets were more fiber-rich and nutrient-dense.

Religion, Ritual, and Sacred Food

Food and religion were inseparable in ancient societies.

Many foods carried symbolic meaning. Bread, wine, milk, honey, and meat were associated with gods, life, fertility, or sacrifice. Certain animals or plants were forbidden, while others were sacred.

Ritual meals reinforced social bonds and cosmic order. Offerings to gods often mirrored human diets, suggesting that divine beings shared the same needs as mortals.

Fasting, feasting, and dietary restrictions shaped religious calendars. Food marked transitions—birth, marriage, death, harvest, and renewal.

Priests and temples often controlled food production and distribution, further linking diet to power and belief.

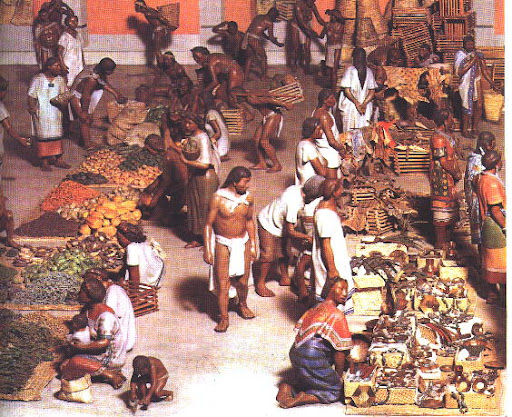

Trade, Exchange, and Early Food Globalization

Although most diets were local, ancient trade slowly expanded food diversity.

Spices, salt, dried fruits, wine, olive oil, and fermented sauces traveled along trade routes. These foods were expensive and prestigious, signaling wealth and connection.

Trade spread crops beyond their original regions. Wheat moved across continents. Rice expanded beyond river valleys. Spices transformed cuisines far from their source.

Food exchange also spread techniques—irrigation methods, preservation practices, cooking tools, and recipes migrated with traders and conquerors.

This slow globalization reshaped diets long before modern times.

Health, Nutrition, and the Ancient Body

Ancient diets were shaped by necessity, but they often supported strong physical health.

High levels of physical activity balanced calorie intake. Diets were rich in fiber, unprocessed foods, and seasonal variety. Obesity was rare outside elite classes.

However, malnutrition, famine, and food shortages were constant threats. Poor harvests, war, and climate shifts could devastate populations.

Dental remains, bones, and mummies reveal both strengths and weaknesses of ancient diets—strong bones in some cultures, signs of deficiency in others.

Food was always a balance between abundance and risk.

Rethinking Ancient Food Systems Today

Studying ancient diets challenges modern assumptions about progress.

Ancient food systems were local, sustainable, and deeply integrated into social life. Waste was minimal. Preservation was essential. Diversity was valued.

While ancient societies lacked modern science, they understood food through experience, observation, and tradition. Many of their practices are being rediscovered today in discussions about sustainability, fermentation, and seasonal eating.

Food connected people to land, time, and community in ways modern systems often struggle to replicate.

In understanding how ancient people ate, we don’t just learn about the past—we gain insight into what it means to eat as humans, shaped by environment, culture, and shared survival.