Poland’s story is one of constant movement, resilience, and reinvention. Over more than a thousand years, this land in the heart of Europe has shifted borders, systems of power, and cultural identities, yet it has managed to preserve a strong sense of continuity. What makes Polish history especially fascinating is not just the dramatic events — wars, partitions, uprisings — but the way society repeatedly rebuilt itself after near-total collapse. To understand Poland, you have to see its past as a long conversation between survival and ambition.

In popular culture, Poland’s history is sometimes introduced through fast-paced visual summaries, including famous animated projects created to represent the country internationally, such as the Expo 2010 presentation in Shanghai. Compressing a millennium into a few minutes is impressive, but the real story unfolds in layers, shaped by geography, neighboring powers, and internal political experiments that were often far ahead of their time.

Ancient Roots and Early Settlements

Long before the idea of a Polish state existed, the lands that now form Poland were home to a mosaic of tribes. During the Iron Age, the region saw the presence of Celts, Scythians, Germanic clans, Sarmatians, Balts, and early Slavic groups. These peoples did not form a unified political entity, but they left behind trade routes, burial sites, and cultural influences that would later blend into Slavic traditions.

The most important ancestors of modern Poles were the West Slavic tribes known as the Lechites. Among them, the Polans — whose name roughly means “people of the open fields” — became dominant in the lowlands of the North-Central European Plain. This geographical setting mattered deeply. Poland lacked strong natural borders like mountains or seas on most sides, making it both a crossroads and a battleground throughout history. The openness that allowed trade and cultural exchange also invited invasions.

The Birth of the Polish State and Christianization

The emergence of Poland as a recognizable state occurred in the 10th century. The Piast dynasty, the first ruling house, unified several tribes under a single authority. Duke Mieszko I stands at the foundation of Polish statehood. His decision to adopt Western Christianity in 966 was not only a religious act but a strategic one. By aligning Poland with Latin Christendom, Mieszko secured international recognition and protection against forced conversion by neighboring powers.

Christianization reshaped Polish society. It introduced literacy through Latin, connected Poland to European political networks, and laid the groundwork for administration and law. Churches and monasteries became centers of learning and record-keeping. While pagan traditions did not disappear overnight, Christianity gradually provided a shared framework that unified the population.

The Piast Kingdom and Early Expansion

In 1025, Mieszko’s son, Bolesław I the Brave, crowned himself king, transforming the duchy into a kingdom. His reign was marked by military campaigns and territorial expansion, which elevated Poland’s status among European powers. Bolesław’s ambitions reflected a broader medieval pattern: rulers sought legitimacy through conquest, alliances with the Church, and dynastic prestige.

After periods of fragmentation and internal struggle, the Piast state regained strength under Casimir III the Great in the 14th century. Casimir is remembered not primarily as a conqueror, but as a reformer and builder. He strengthened towns, codified laws, improved defenses, and promoted economic development. His reign brought relative stability and prosperity, even though he died in 1370 without a male heir, ending the Piast line.

The Jagiellonian Era and the Polish Renaissance

The transition to the Jagiellonian dynasty marked a turning point. Through dynastic unions and alliances, Poland became closely tied to Lithuania, one of the largest states in Europe at the time. This relationship culminated in deeper political integration and cultural exchange.

Between the 14th and 16th centuries, Poland experienced a flourishing Renaissance. Universities expanded, art and literature thrived, and Polish nobles increasingly participated in European intellectual life. The kingdom grew territorially and culturally, absorbing diverse populations and traditions. This era also saw the gradual spread of Polonization, as the Polish language and customs gained prominence among elites across the realm.

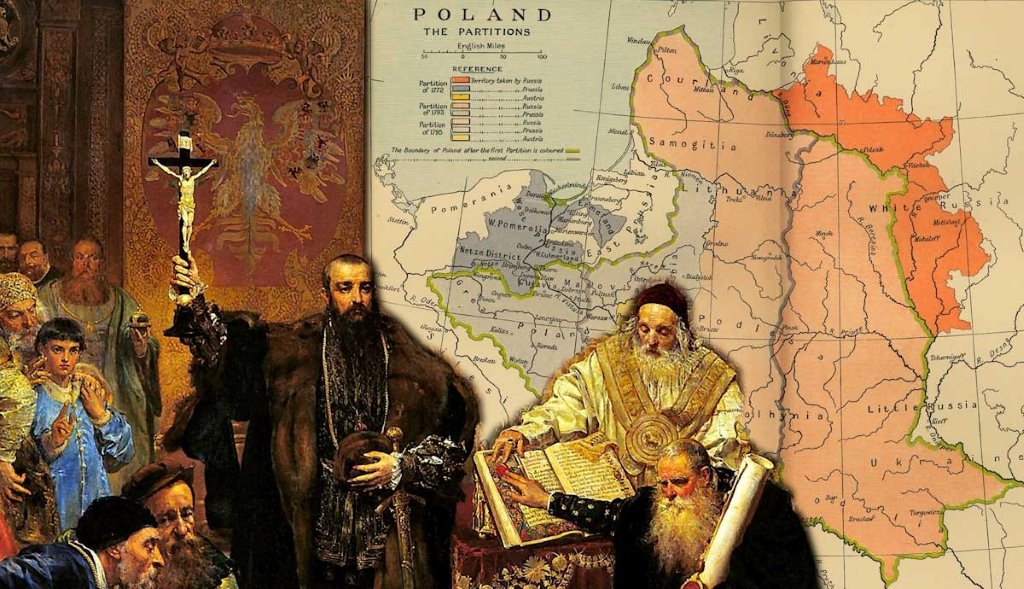

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

In 1569, the Union of Lublin formally created the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a vast state stretching from the Baltic to near the Black Sea. It was one of the largest political entities in Europe and, in many ways, one of the most unusual. The Commonwealth developed a system known as noble democracy, where the nobility wielded significant power and the king was elected rather than inheriting the throne automatically.

This political model offered freedoms rare for the era, including religious tolerance and legal protections for nobles. At its best, the Commonwealth combined prosperity with cultural diversity, hosting Catholics, Orthodox Christians, Protestants, Jews, and Muslims within its borders. However, the same system that empowered the nobility also weakened central authority. Over time, excessive veto powers and internal rivalries made effective governance increasingly difficult.

Decline, Reform, and Approaching Crisis

By the mid-17th century, the Commonwealth entered a period of decline. A series of devastating wars, including invasions by Sweden and conflicts with neighboring powers, drained resources and population. The political system struggled to adapt to new realities, and foreign influence grew stronger as internal paralysis set in.

Despite these challenges, the late 18th century brought ambitious reform efforts. Polish thinkers and statesmen attempted to modernize the state, culminating in the Constitution of 3 May 1791 — the first modern constitution in Europe. It sought to strengthen central authority, limit destructive political practices, and protect citizens. Unfortunately, neighboring empires viewed a reformed Poland as a threat.

In 1795, after successive invasions and partitions carried out by Russia, Prussia, and the Habsburg Monarchy, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth ceased to exist.

At this point, Poland vanished from the political map of Europe, but not from the consciousness of its people. The next chapters would be defined by resistance, memory, and the long struggle to regain sovereignty.

Life Under the Partitions

After 1795, Poland existed only as an idea sustained by language, culture, and collective memory. Its former territories were divided between three empires, each imposing its own political system and policies. In the Russian-controlled areas, efforts were made to suppress Polish identity through censorship, forced Russification, and the limitation of Polish education. Prussia pursued Germanization, reshaping administration and schooling to weaken Polish cultural influence. The Austrian-controlled regions, while restrictive, allowed slightly more cultural autonomy, particularly in Galicia.

Despite these pressures, Polish society remained remarkably resilient. Intellectuals, writers, and artists played a central role in keeping national consciousness alive. Literature became a substitute for statehood, with poetry and novels often carrying political meaning disguised as romantic or historical themes. Music and painting also served as quiet acts of resistance, reinforcing a shared sense of identity across divided lands.

Uprisings and the Struggle for Independence

Throughout the 19th century, Poles repeatedly attempted to restore independence through armed uprisings. The November Uprising of 1830 and the January Uprising of 1863 were among the most significant. Although both ultimately failed militarily, they left a deep mark on national consciousness. These revolts reinforced the idea that independence was worth sacrifice, even when success seemed unlikely.

Following each failed uprising, repression intensified. Executions, deportations to Siberia, and the confiscation of property were common. Yet these harsh responses often had the opposite effect of what occupying powers intended. Instead of erasing Polish identity, repression strengthened it, turning fallen insurgents into symbols of national martyrdom.

At the same time, many Poles turned toward pragmatic strategies. Economic development, education, and grassroots organization became tools for survival. Cooperatives, underground schools, and cultural associations quietly prepared society for the moment when political opportunity would return.

The Road Back to Statehood After World War I

The outbreak of World War I reshaped Europe in ways few could have predicted. The three empires that had partitioned Poland found themselves weakened by years of warfare, internal unrest, and economic collapse. Polish political leaders seized this moment, lobbying international powers and organizing military units to fight alongside different alliances in hopes of restoring independence.

In 1918, as the war ended and empires crumbled, Poland re-emerged as a sovereign state. The Second Polish Republic was established after more than a century without independence. Rebuilding the country was an enormous challenge. Borders were contested, infrastructure was uneven, and society had developed under three different administrative systems. Still, the new state moved quickly to establish institutions, reform education, and integrate its diverse regions.

The Interwar Years and Fragile Stability

Between the two world wars, Poland worked to define itself politically and culturally. The period was marked by both creativity and tension. On one hand, literature, cinema, and science flourished. On the other, political instability, economic inequality, and unresolved ethnic tensions created internal strain.

Poland’s geopolitical position remained precarious. Situated between two powerful and increasingly aggressive neighbors, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, the country faced growing external threats. Diplomatic efforts aimed at maintaining independence through balance ultimately proved insufficient against the realities of totalitarian expansion.

World War II and National Catastrophe

In 1939, Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany from the west and the Soviet Union from the east, triggering World War II. The occupation that followed was one of the darkest chapters in Polish history. Millions of citizens were killed, including Jews, Poles, Roma, and other targeted groups. Cities were destroyed, cultural heritage was looted or annihilated, and entire communities vanished.

Despite this devastation, resistance never ceased. Underground networks operated across occupied territory, maintaining secret education systems, publishing banned materials, and organizing armed resistance. A Polish government-in-exile functioned abroad, coordinating efforts with Allied forces. Polish pilots, soldiers, and intelligence officers played vital roles on multiple fronts of the war.

Communist Rule and a Reshaped Nation

As Nazi forces retreated in 1944 and 1945, Soviet troops advanced westward. Poland emerged from the war devastated and fundamentally altered. Borders were shifted west, resulting in massive population transfers and the loss of the country’s historic multi-ethnic character. Entire regions were repopulated, and society had to adapt to new realities almost overnight.

A communist government, aligned with Moscow, took power. The Polish People’s Republic was established, introducing a planned economy and suppressing political opposition. While industrialization and education expanded in some areas, censorship and surveillance became everyday realities. Public dissent was risky, yet never fully extinguished.

Solidarity and the Return of Democracy

By the late 20th century, economic stagnation and social frustration reached a breaking point. The Solidarity movement, born in shipyards and factories, transformed labor protests into a nationwide push for political reform. What made Solidarity unique was its combination of grassroots organization, intellectual support, and moral authority.

Through negotiations rather than violent confrontation, Poland transitioned away from communism. In 1989, democratic reforms paved the way for free elections and the creation of the modern Polish state, often referred to as the Third Polish Republic.

Modern Poland and Historical Continuity

Today’s Poland is a democratic republic with a market-based economy and active participation in European and global institutions. Its modern identity is deeply shaped by history, not as a burden, but as a source of perspective. The repeated loss and recovery of sovereignty left a lasting imprint on political culture, public memory, and national values.

Poland’s history is not a straight line of progress or decline. It is a story of endurance, adaptation, and cultural strength. Through centuries of shifting borders and systems, the idea of Poland survived long before the state itself returned — a rare and powerful testament to the resilience of a nation.