Over the course of six turbulent years, stretching from the opening shots on 1 September 1939 to the final surrender on 2 September 1945, the world witnessed a level of devastation unmatched in human history. Entire continents were scarred as total war unfolded between the Axis and Allied powers. Cities vanished under firestorms, entire regions were depopulated, and somewhere between seventy and eighty million people—soldiers, civilians, prisoners, the displaced—lost their lives. The conflict drained national treasuries, shattered empires that had dominated global politics for centuries, and forced humanity to confront the darkest capabilities of modern warfare.

Characterised by mass atrocities, systematic genocide, strategic bombing campaigns, starvation, forced labour, and the unprecedented use of nuclear weapons, the war reshaped the moral and political landscape of the modern era. The suffering it produced accelerated the creation of frameworks intended to protect human rights and prevent similar catastrophes, shaping international law and guiding diplomatic norms for generations. The conflict’s end brought about the founding of the United Nations, envisioned as a body to foster dialogue and prevent further global wars—yet it also opened the door to a new and uneasy age as tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union hardened into a long, chilling rivalry known as the Cold War.

The historian Margaret MacMillan once reflected that the world after the First World War still felt capable of recovering and returning to familiar routines, but 1945 was different. It marked what many later described as a kind of “Year Zero,” a point at which societies had to rebuild not simply physical infrastructure but their very assumptions about government, security, and humanity. The trauma of the Second World War left deep and lasting imprints, its memories resonating long after the rubble had been cleared and economies revived.

Yet the path to such devastation did not begin suddenly in 1939. Most historians point to the closing days of the First World War, where decisions made in exhausted capitals planted the seeds of future conflicts. When the Treaty of Versailles was drafted in 1918, its authors—working amid grief, anger, and political pressure—assigned full blame for the war to Germany and Austria-Hungary. The treaty stripped territories, imposed staggering financial penalties, and forced military restrictions meant to weaken Germany’s ability to wage war again. These measures, especially the demilitarisation of the Rhineland and the abolition of the German air force, created widespread resentment across German society.

Some scholars argue that these terms were unnecessarily punitive and fed a growing anger that simmered through the 1920s and 1930s. Yet, as the BBC has noted, it would be overly simplistic to claim that Versailles alone triggered the Second World War. Rather, it created a volatile environment—one that opportunistic leaders would later exploit. German frustration, economic instability, political fragility, and a wounded national identity became components of a larger, combustible mixture that extremist ideology would ignite.

The rise of Hitler

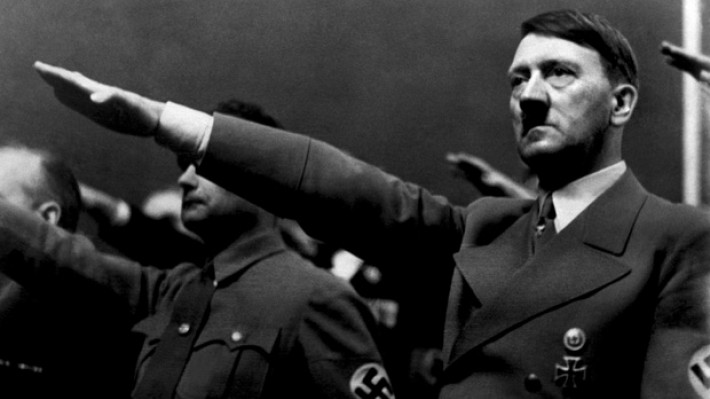

In January of 1933, Germany marked a turning point when Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor—a moment that would fundamentally reshape the nation and ultimately the world. Commemorations decades later prompted reflection on how such a rise had been possible, with Angela Merkel noting during an exhibition opening in the former SS headquarters that far too many individuals in the early 1930s had responded with indifference rather than resistance.

Hitler’s origins were far removed from the image he later cultivated. As a young man, he pursued painting and drifted through periods of poverty before enlisting in the Bavarian army at twenty-five, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War. His service was unremarkable except for his willingness to carry messages across dangerous front lines. Twice decorated for bravery, he also suffered serious injuries—once from an artillery shell in 1916 and again from a mustard gas attack in 1918 that temporarily blinded him.

Germany’s defeat at the end of the war left him adrift. Seeking direction, he joined the intelligence branch of the drastically reduced German military. His assignment to monitor the German Workers’ Party proved transformative. Within that organisation, under the influence of figures like Anton Drexler, Hitler absorbed and expanded upon ideas rooted in virulent anti-communism and antisemitism. By September 1919, he openly declared that removing Jewish people from Germany must be a political goal—a statement that foreshadowed the brutality to come.

Hitler quickly advanced within the party. He renamed it the National Socialist German Workers’ Party and introduced the now-infamous swastika as its emblem. His speeches drew immense crowds; his message resonated with citizens disillusioned by economic crises, political instability, and the humiliation many associated with the Treaty of Versailles. Large donors viewed him as a potential saviour of German strength, and by leveraging the vulnerabilities of the Weimar Republic, he positioned himself as a forceful alternative to struggling democratic leaders.

Through the 1920s and early 1930s, he expanded his influence until he became chancellor. When President Paul von Hindenburg died, Hitler seized the opportunity to merge the roles of president and chancellor, declaring himself Führer and assuming absolute control. Every paramilitary force in Germany—from the SS to the SA—fell under his authority.

Hitler’s fury toward the Treaty of Versailles became a cornerstone of his rhetoric. He criticised what he portrayed as an unjust settlement and framed himself as the leader who would restore Germany’s pride. By the mid-1930s, the geopolitical landscape surrounding Germany included weak and divided states, making expansion both tempting and strategically feasible. These conditions provided fertile ground for Hitler’s ambitions, enabling Germany to rearm and prepare for a renewed bid to dominate Europe.

Events of 1939

The 1930s were marked by a series of international crises that pushed Europe steadily toward a second major conflict. The Spanish Civil War became a testing ground for German and Italian military power, while the Anschluss—Germany’s annexation of Austria—demonstrated Hitler’s willingness to defy international agreements. The subsequent occupation of the Sudetenland, followed by the dismantling of Czechoslovakia, showed that diplomatic concessions only encouraged further aggression.

The immediate spark for the Second World War came on 1 September 1939, when German forces invaded Poland. This invasion revealed a new style of warfare that would come to define German military strategy: blitzkrieg. This approach began with overwhelming aerial bombardment, aimed at crippling air defenses, communication networks, transportation routes, and ammunition supplies. In its wake came rapid, coordinated ground assaults involving tanks, motorised brigades, artillery, and infantry. Once enemy lines were destabilised, German troops surged forward, leaving confusion and destruction behind them.

Poland was swiftly overwhelmed. A combination of strategic misjudgments and Germany’s formidable technological advantage made resistance nearly impossible. Hitler had anticipated a quick victory for two reasons the BBC later highlighted. First, he believed that Germany’s armoured divisions would crush Polish defenses with unprecedented speed. Second, he assumed that British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier lacked the resolve to oppose him militarily. His past experiences with their diplomatic negotiations appeared to support that view.

Chamberlain’s policy, now referred to as “appeasement,” has often been criticised for enabling Nazi expansion. Yet, as some historians argue, many leaders in Britain and France genuinely hoped that compromise might preserve peace in a fragile, recovering Europe. After the invasion of Poland, however, that hope vanished. Within two days, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Though their support for Poland was limited and delayed, the declarations formally marked the beginning of a conflict that would engulf the world and reshape the course of the twentieth century.