The next few decades will redefine everything we think we know about commercial aviation. Behind the scenes, manufacturers and researchers are grappling with a future in which global air traffic could grow seven-fold and environmental pressures intensify dramatically. The increasing demand for long-distance travel collides with the urgent need for cleaner skies, pushing the aviation industry toward a technological transformation unlike anything it has attempted before. What emerges by 2050 could feel closer to a reinvention of flight than a simple upgrade of the aircraft we use today.

Energy systems, propulsion technology, aircraft shapes, onboard computing, and even the way we build planes are all heading toward a profound shift. While travelers may still board something recognizable as an airplane, nearly everything behind the experience may function differently — cleaner power, intelligent materials, biologically inspired structures, and digitally coordinated aircraft that respond moment-by-moment to their environment. Looking ahead requires recognizing how fast these technologies are advancing and how dramatically they will reshape aviation’s role in a globalized world.

How Future Airplanes Will Look by 2050

The Drive Toward Full Electrification of Future Aircraft

The most decisive step toward a greener future for aviation is the transition from combustion-powered aircraft to commercial airliners propelled entirely by electric energy. At the moment, conventional jet engines dominate the skies, delivering hundreds of terawatts of movement every year but also releasing enormous quantities of carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxides. To change this, engineers need power sources that deliver enormous output with extremely low weight — a challenge that stands at the center of aircraft electrification.

Battery energy density has been the main technological obstacle. Aircraft demand high power-to-mass ratios, and traditional batteries simply could not deliver enough energy without adding debilitating weight. Yet the trajectory of battery development tells an encouraging story. Lithium-ion energy density rose from just over a hundred watt-hours per kilogram in the mid-1990s to roughly three hundred today, a number that would have seemed unrealistic to many engineers just two decades ago. Several leading researchers and innovators, including prominent figures in the electric vehicle sector, have argued that once batteries reach four hundred watt-hours per kilogram — which now appears feasible within the coming decade — long-range electric aircraft become practical rather than speculative.

This shift isn’t driven only by environmental concerns. Solar power continues to drop in cost year after year, already becoming one of the cheapest electricity sources in many regions. Meanwhile, kerosene jet fuel exhibits the opposite trend, burdening airlines with fluctuating expenses. As battery manufacturing scales and refinements reduce costs further, the economic incentive to adopt electric propulsion will become impossible for airlines to ignore. What once felt like a distant dream — a large commercial aircraft powered solely by electricity — is rapidly being pushed into the realm of commercial inevitability.

VoltAir, all-electric aircraft concept. EADS

Because battery improvements arrive gradually and aircraft lifespans stretch across decades, the transformation of the global fleet won’t be instant. The average commercial passenger jet serves for more than twenty years, and cargo aircraft often remain in operation for even longer. That means electrification must begin long before its environmental benefits can be fully realized — and airlines will increasingly weigh long-term operational costs against the upfront price of buying next-generation aircraft.

The Role of Biofuels During the Transition Phase

The aviation industry cannot wait for electrification to become dominant before seeking cleaner alternatives. This is where advanced biofuels enter the equation. Although they do not eliminate emissions entirely, these fuels can reduce carbon output significantly depending on production methods and land use. The ability to blend biofuels with conventional jet fuel without redesigning engines makes them one of the few immediate options for lowering aviation’s environmental impact.

Biofuel adoption, however, faces economic complications. Producing these fuels at the industrial scale required for global aviation is costly, and equalizing their price with fossil-based jet fuel remains several years away. Even so, the technology is viable, and its integration represents a practical stepping stone while the world prepares for fully electric fleets. As aircraft manufacturers concentrate their research on future propulsion systems and revolutionary designs, the interim use of biofuels will buy valuable time to reduce emissions and ease the pressure on rapidly growing air traffic networks.

Rising Computational Power and the Dawn of Intelligent Aircraft Structures

The capabilities of aircraft have always been shaped by the limits of onboard computing. Early jets flew with systems that processed only basic commands, and safety depended heavily on manual operation. Today’s aircraft operate with vastly superior digital control systems, yet they still pale in comparison to what is coming. The exponential growth of computational power suggests that by the 2030s and 2040s, onboard computers priced at consumer-level costs could exceed the raw processing capacity of the human brain.

This explosion in capability is matched by the shrinking size of digital components. Transistors that once measured thousands of nanometers now approach dimensions far smaller than a red blood cell. With ongoing advancements in graphene and other next-generation materials, the miniaturization of computing elements will push boundaries even further.

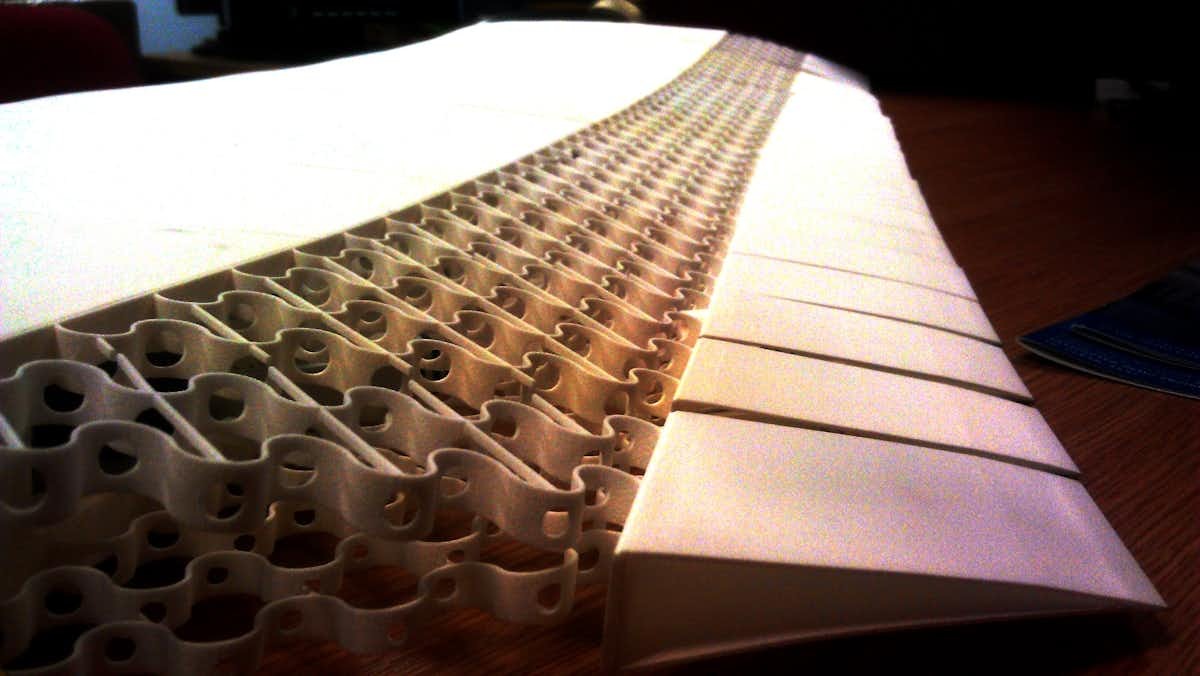

When these trends converge with manufacturing improvements such as high-precision 3D printing, aviation enters a new world — aircraft with digital nervous systems. Thousands or even millions of micro-sensors could be embedded throughout an airframe, continually reporting on forces, temperature gradients, airflow patterns, and structural stress. Instead of reacting to conditions, the aircraft would anticipate them, altering its surface shape or wing flexibility in real time to maintain peak efficiency.

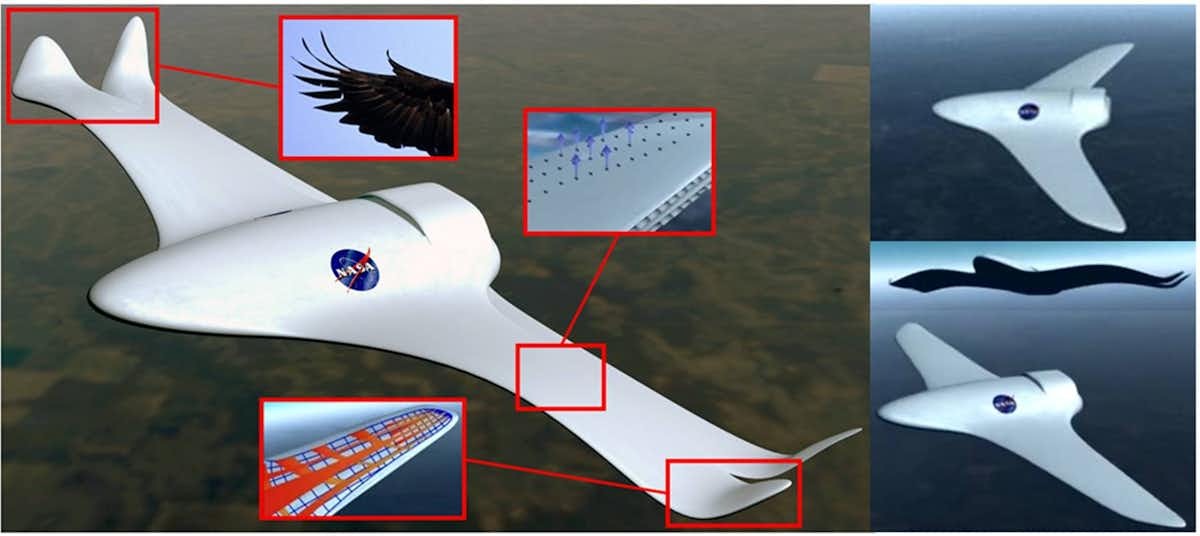

Such adaptive structures draw not only from mechanical engineering but from biological inspiration. Birds change their wing curvature and feather alignment fluidly as they maneuver. Future aircraft may one day mirror this elegance, shifting their aerodynamic profile without relying on rigid control surfaces that have defined aviation for more than a century.

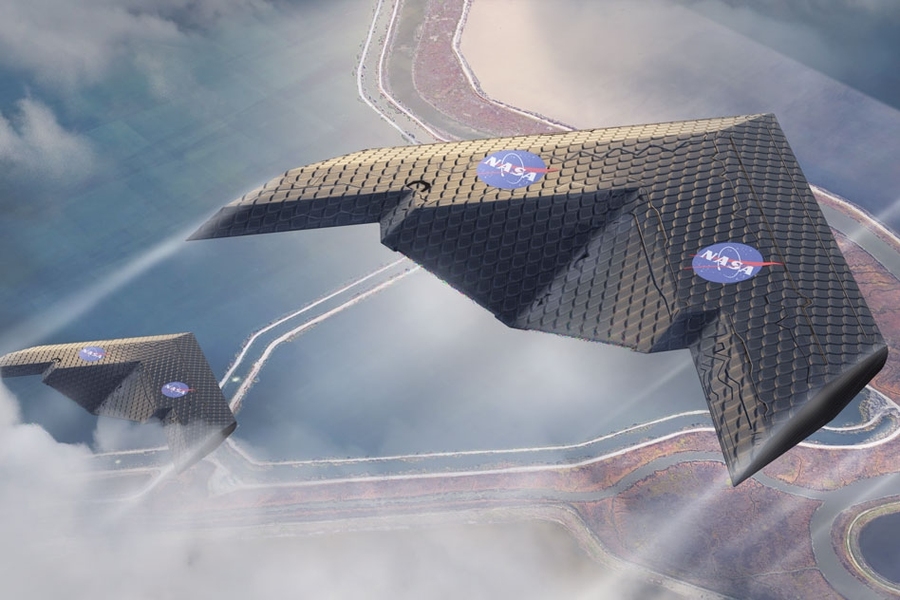

Morphing Wing Designs and the Future Beyond Traditional Airframes

Conventional wings are already approaching their aerodynamic limits. Engineers have refined them to extraordinary efficiency, yet traditional structures impose natural constraints. Today’s aircraft rely on fixed geometry, using flaps, ailerons, elevators, and rudders to shape airflow. But these moving parts add drag, create mechanical complexity, and place limits on how efficiently an aircraft can operate.

Adaptive, morphing wings represent a fundamental shift. Instead of operating like machines with isolated components, the wings of future airliners may behave almost like living structures — twisting subtly to reduce drag, bending to stabilize turbulence, or reshaping entirely for takeoff, cruise, or landing. Removing reliance on large tail assemblies becomes possible through advanced propulsion systems capable of directing thrust in multiple directions, eliminating the weight and drag of traditional rear control surfaces.

This vision pushes the industry beyond mere improvements and into conceptual reinvention. Aviation’s earliest designers were constrained by the materials and engineering of their era. Modern technology removes those barriers, allowing ideas once dismissed as unrealistic to become the foundation of next-generation aircraft.

Industry Concepts Shaping Aviation’s Vision for 2050

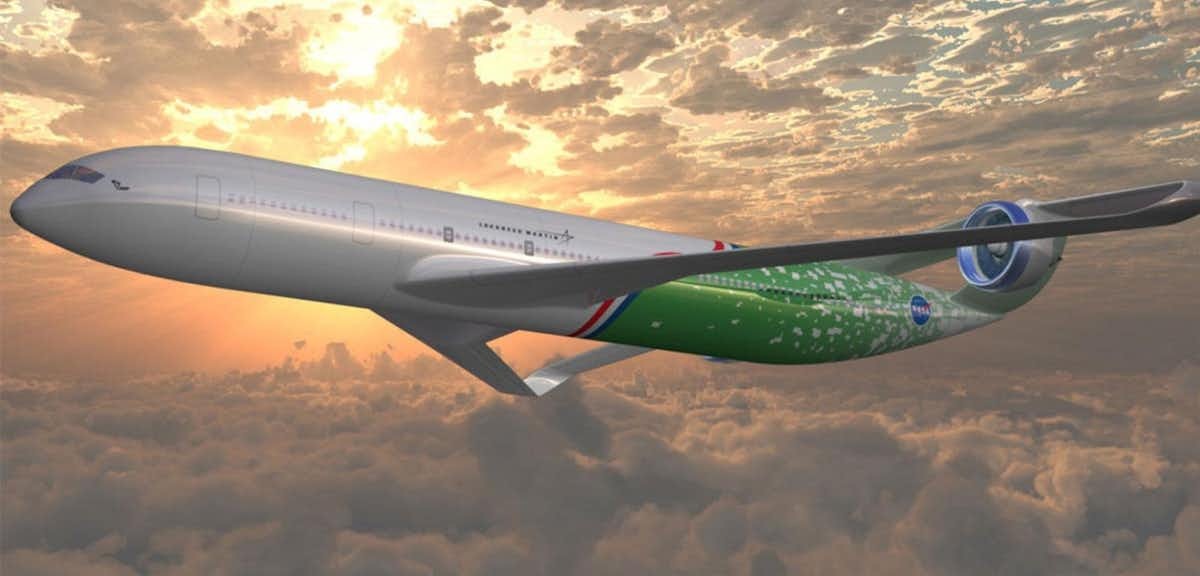

Major aerospace companies are not waiting for 2050 to begin exploring these possibilities. Hybrid-electric propulsion systems, blended wing bodies, and transparent cabin structures are already moving through conceptual development stages. Some designs focus on reducing emissions; others aim to reimagine passenger comfort or optimize fuel usage through radical new shapes.

The blended wing body, for instance, merges the fuselage and wing into a single aerodynamic form, distributing lift more evenly and reducing drag. Airlines could achieve large fuel savings while gaining spacious interiors that change how passengers experience long-haul travel.

Electric propulsion research is simultaneously reshaping assumptions about what aircraft should look like. NASA, Airbus, and multiple universities are experimenting with distributed propulsion — multiple small motors instead of two large engines — which creates redundancy, efficiency, and entirely new structural possibilities.

The future outlined by these concepts does not represent a single path but an array of technologies converging toward quieter, cleaner, smarter aircraft.

How Passenger Experience Will Change by 2050

For travelers, the most noticeable changes will not be hidden inside battery packs or behind composite skins, but in how the entire journey feels from boarding to landing. As aircraft become more efficient, quieter, and digitally integrated, cabin design and passenger experience will evolve alongside the technology that keeps them in the air.

Cabins in 2050 are likely to be far more flexible than today’s rigid layouts. Instead of a fixed grid of rows and seats, airlines may use modular seating zones that can be rearranged depending on route length, time of day, or passenger demand. Short regional flights could favor high-density layouts with clever ergonomic seats that maximize comfort in limited space. Long-haul flights might instead offer more open social spaces, quiet pods for sleep, and work-focused areas with integrated connectivity and lighting tailored to prevent fatigue.

The digital environment will transform as well. Windows could be replaced or augmented by smart panels, projecting ultra-high-resolution views fed from external cameras, adjusted for brightness, turbulence, and even passenger mood. Personalized information—flight progress, connection details, or real-time environmental impact data—could appear on seat-back screens, personal devices, or subtle projection interfaces built into the cabin architecture.

Air quality and pressure systems will improve, too. Electric and hybrid-electric aircraft remove some of the constraints currently imposed by engine bleed-air systems, allowing designers to fine-tune humidity and pressure for human comfort instead of purely mechanical requirements. Higher cabin humidity and slightly increased pressure can reduce dehydration, headaches, and the sense of “post-flight exhaustion” that many long-haul travelers know too well.

Noise levels inside the cabin will drop significantly. Electric propulsion and refined aerodynamics reduce external noise, while active noise control systems embedded in the cabin structure can cancel specific frequency ranges. The result is a quieter, calmer environment, with less constant engine rumble and more subtle, designed soundscapes—soft cues for boarding, meal service, or sleep periods, instead of disruptive announcements.

Smarter Skies: Air Traffic and Autonomy

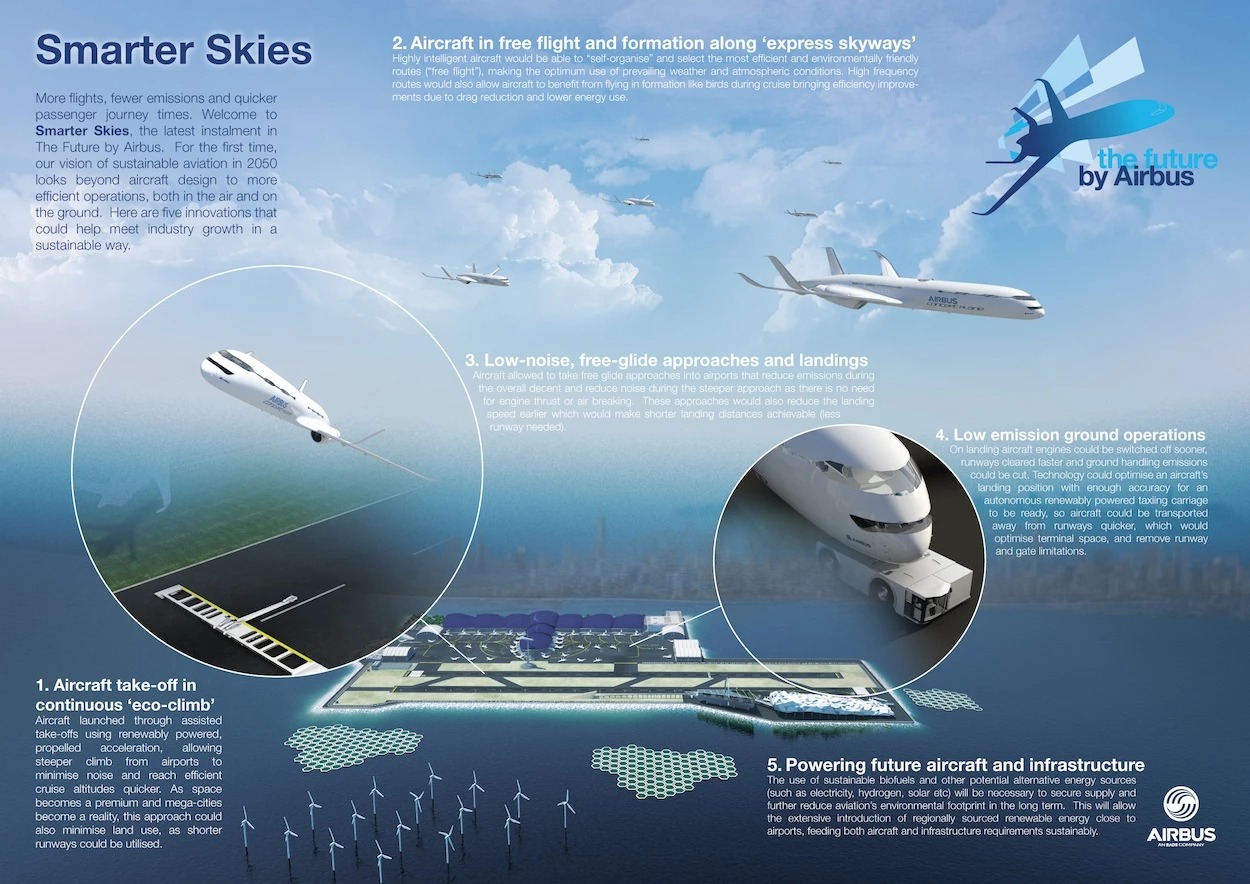

The transformation of aircraft themselves will be matched by an equally profound change in how they move through the sky. Air traffic management systems are already shifting from radar-based tracking to satellite-supported navigation and digital communication. By 2050, that evolution will go much further, with aircraft operating as coordinated participants in a dynamic, data-rich airspace.

Future commercial aircraft will rely heavily on advanced autopilot and decision-support systems that continuously calculate optimal routes based on weather, congestion, energy use, and environmental impact. Rather than following rigid, pre-defined air corridors, aircraft will flow along flexible “sky paths,” adjusted in real time to reduce delays and cut unnecessary fuel or energy consumption. This kind of adaptive routing becomes far more effective when every aircraft in a region shares data about position, speed, engine performance, and even the state of the atmosphere around it.

Levels of autonomy will rise step by step. Pilots will still play a crucial role, especially in oversight, decision-making, and irregular situations, but the workload will shift dramatically. Many routine tasks—optimizing descent paths, spacing aircraft on approach, managing climb performance—will be handled by intelligent systems that coordinate directly with ground-based traffic control AI. Over time, this relationship will feel less like “pilots talking to controllers” and more like human experts collaborating with powerful digital systems that handle calculation-heavy tasks without fatigue or distraction.

Safety margins will grow accordingly. Modern commercial aviation is already extraordinarily safe, but predictive systems will push risk even lower. Aircraft will monitor their own components in real time, detecting subtle patterns that indicate potential failures long before they become dangerous. Maintenance can then be scheduled proactively, with parts replaced or repaired when data, not just time, suggests they are reaching the end of their reliable life.

Materials, Manufacturing, and Sustainability

One of the quiet revolutions behind future aircraft will take place in factories rather than on runways. The materials that form the wings, fuselage, and internal structures will move far beyond traditional metals and basic composites. Advanced carbon-fiber blends, nano-engineered resins, and even bio-inspired materials will create structures that are lighter, stronger, and more resilient than those in use today.

Additive manufacturing—high-precision 3D printing and related techniques—will allow engineers to design components with internal geometries impossible to create using conventional machining. Lattice structures, variable-density supports, and organically shaped reinforcements can provide strength exactly where it is needed, removing unnecessary weight while maintaining safety. This level of design freedom is especially useful for electric aircraft, where every kilogram saved contributes directly to extended range or higher payload.

Sustainability will also extend to the aircraft lifecycle. New materials and manufacturing methods will be developed with recycling and reuse in mind. Instead of scrapping retired airframes and sending large portions to waste, future designs may break down more cleanly into recyclable elements, closing the loop between production and disposal. Some components, particularly modular electronics or propulsion units, could be designed to be removed, updated, and reinstalled on newer platforms, stretching their useful life and reducing the environmental footprint of the overall system.

Even the interior may be built with sustainable, high-performance materials—lightweight panels derived from bio-based sources, upholstery engineered to resist wear while remaining easy to recycle, and cabin elements designed for quick replacement and refurbishment without discarding large structures.

Airports and Ground Operations in an Electric Era

As aircraft technology changes, airports will need to adapt. Electric and hybrid-electric planes create new demands on ground infrastructure, and meeting those demands efficiently can drive major operational changes.

High-capacity charging systems will become as critical as fuel trucks. Some airports may build centralized charging hubs, supplying energy through underground lines to gates where aircraft connect immediately after parking. Others might experiment with battery-swapping systems for smaller regional aircraft, replacing depleted packs with charged ones in a controlled, high-speed operation. Integration with local and national power grids will require careful planning, especially during peak travel times when multiple large aircraft may need high-power charging simultaneously.

Airports themselves will likely increase their use of renewable energy. Large roof surfaces, open land around runways, and nearby industrial zones create natural opportunities for solar, wind, or hybrid renewable installations tailored to support aviation’s new electric demand. Coupled with energy storage systems, airports can manage peak loads, reduce their reliance on fossil-fuel-based grids, and stabilize their operating costs over time.

Ground operations will also become cleaner and quieter. Electric tugs, service vehicles, baggage loaders, and catering trucks are already appearing in some airports. By 2050, it is reasonable to expect that most ground support equipment will be powered electrically, drastically cutting emissions and improving working conditions for ground crews who currently endure high noise and exhaust exposure.

Challenges, Trade-Offs, and the Human Factor

Despite the impressive potential of these technologies, the path to 2050 will not be smooth. Economic pressures, regulatory hurdles, and political debates will shape how quickly airlines can adopt new aircraft and how evenly those advances spread across the globe.

Electric propulsion and advanced materials demand sizable upfront investments. Early aircraft models may cost more than the conventional jets they aim to replace, even if lifetime operational expenses are lower. Airlines will have to balance fleet renewal with short-term financial realities, particularly in competitive markets where margins are thin and small missteps can have severe consequences.

Regulators will face their own balancing act. They must encourage innovation and environmental improvement while preserving aviation’s impeccable safety culture. Certification standards for electric propulsion, morphing structures, or deeply autonomous systems will need to evolve carefully, drawing from new testing methods, simulation tools, and real-world data. That process takes time and demands close cooperation between manufacturers, regulators, pilots, and maintenance professionals.

Then there is the human factor. Travelers may take time to trust radical new aircraft shapes, cabin layouts, or the idea of flying on planes where computers handle much of the work that was once the sole domain of human pilots. Clear communication, transparent safety records, and gradually introduced changes will help build confidence. As with any major technological shift—whether jet engines replacing propellers or glass cockpits replacing analog dials—people adapt when they can see, feel, and understand the benefits.

A Different Kind of Sky

By the time commercial aviation reaches mid-century, the combined effect of electric propulsion, intelligent structures, advanced materials, and redesigned air traffic systems will make the sky feel familiar yet fundamentally renewed. Aircraft may still have wings, cabins, and engines, but they will carry a very different story in their design: one shaped by energy efficiency, environmental responsibility, digital intelligence, and a closer partnership with the natural principles that have governed flight since long before humans joined the air.

What passengers notice may be simple—a quieter cabin, smoother flights, cleaner airports, and a sense that long journeys leave less of a mark on the planet. Behind that experience, however, will be decades of engineering, experimentation, and bold decision-making that reshaped the very idea of what a commercial aircraft can be.