The conversation around the future of American airpower has been heating up, especially as global military dynamics shift and great-power competition becomes more pronounced. In recent years, senior Air Force leaders and independent defense analysts have warned that the current force structure is too small, too old, and too limited for the kinds of challenges posed by China and Russia. Those concerns are no longer theoretical; they’ve become a central part of national defense planning.

Last September, Air Force leadership openly stated that the United States would need 386 operational squadrons to face the next era of near-peer competition. Even that number, bold as it sounded at the time, may fall short. A congressionally mandated study from the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) — now circulating among lawmakers — suggests that the Air Force will require an even more ambitious expansion, along with entirely new classes of aircraft that are not currently being built.

CSBA’s assessment goes far deeper than simply saying “more aircraft are needed.” It argues for the development of stealthy, weaponized drones; reconnaissance aircraft capable of slipping into heavily defended airspace; and a radically reimagined refueling force designed for a world where traditional tanker aircraft may no longer survive. The study pushes the Air Force toward a future built around penetrating platforms, distributed systems, and unmanned technologies that complement — rather than mimic — today’s fleet.

What Aircraft the US Air Force Needs to Win Against China and Russia

Rethinking the Air Force force structure

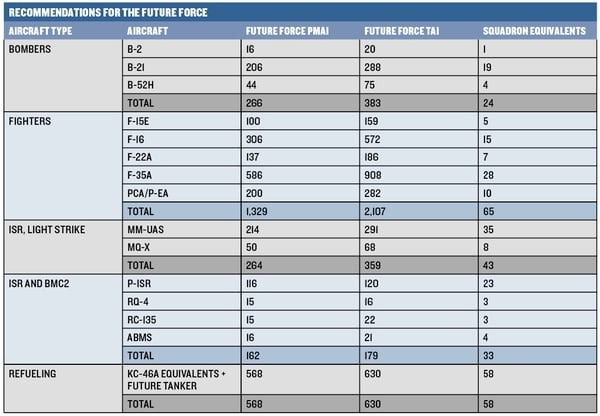

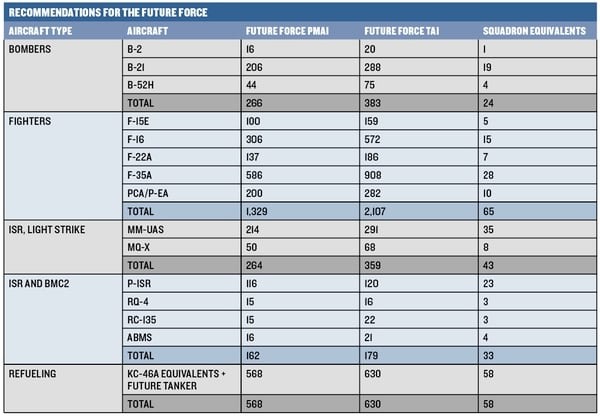

Congress tasked the Air Force, MITRE Corporation, and CSBA with independent evaluations of what the future force should look like. When CSBA delivered its findings, the results were stark. Nearly every major mission area — bombers, tankers, fighters, and ISR platforms — showed substantial gaps between current capabilities and what would be required in a simultaneous conflict against two major powers.

The CSBA researchers concluded that the most urgent shortfalls exist in three specific fleets: bombers, tankers, and unmanned strike/reconnaissance aircraft. While fighter numbers must grow, the Air Force’s ability to deliver long-range strikes and sustain operations deep inside contested airspace is considered the critical bottleneck.

To illustrate, the study recommends increasing the number of operational bomber squadrons from the current nine to twenty-four, nearly tripling the present force. This vision doesn’t assume a specific timeline — partly because the proposed future force includes not-yet-designed aircraft — but it does underscore how dramatically the U.S. inventory must evolve.

Fighter squadrons would need to expand from 55 to 65, and the tanker force — already stretched thin and aging rapidly — would require 58 squadrons, up from today’s forty. Meanwhile, long-endurance strike/reconnaissance drones, typified today by the MQ-9 Reaper, would need to grow from 25 to 43 squadrons to meet global demand.

Curiously, CSBA proposes a reduction in traditional C2/ISR squadrons from forty to thirty-three. But that drop should not be confused with a reduction in intelligence capability; instead, CSBA argues for a transition away from large, vulnerable, aging aircraft such as the E-8 JSTARS toward a distributed network of sensors and platforms, similar to the developing Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS). This shift would improve resilience, expand coverage, and reduce the vulnerability of command-and-control nodes in high-end conflict.

A debate still unfolding

The organization declined to elaborate publicly, since Congress has not yet been formally briefed. The report briefly appeared on a Defense Department website before being removed, adding to the anticipation and speculation surrounding its findings.

What the Air Force believes it needs

Although CSBA’s assessment is extensive, it contrasts notably with the Air Force’s own “The Air Force We Need” internal study. The service estimates that 386 operational squadrons will be required by 2030, including several mission areas that CSBA didn’t evaluate in detail — such as space assets, cyber units, missile forces, airlift, and combat search-and-rescue.

The Air Force’s internal goal includes:

• 14 bomber squadrons

• 62 fighter squadrons

• 54 tanker squadrons

• 27 strike/reconnaissance UAV squadrons

• 62 C2/ISR squadrons

However, none of these plans have yet been tied explicitly to procurement decisions, and the service has avoided discussing whether programs such as the B-21, the KC-46, or the F-35 will be expanded to meet those numbers. Even more importantly, the Air Force and CSBA made their recommendations based on fundamentally different threat models.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Dave Goldfein said the 386-squadron target aims to defeat one peer adversary while deterring another. CSBA, however, assumes a more extreme scenario: the U.S. must withstand back-to-back conflicts — first with China in the Indo-Pacific, then days later with Russia in Europe. This dual-crisis scenario drives a much larger and more diversified force structure.

An increasingly dangerous battlespace

CSBA’s future-conflict model paints a landscape defined by dense air defenses, mobile missile systems, and coordinated electronic attacks. By the 2030s, Chinese and Russian air-defense networks are expected to become “highly contested” environments where overlapping missile batteries, passive radar, cyber tools, electronic warfare aircraft, and stealth-detecting sensors operate simultaneously.

In such a world, American aircraft would face threats from every direction — not just from the ground or from hostile fighters, but from integrated networks designed to deny access, disrupt communications, jam sensors, and hunt down vulnerable support aircraft.

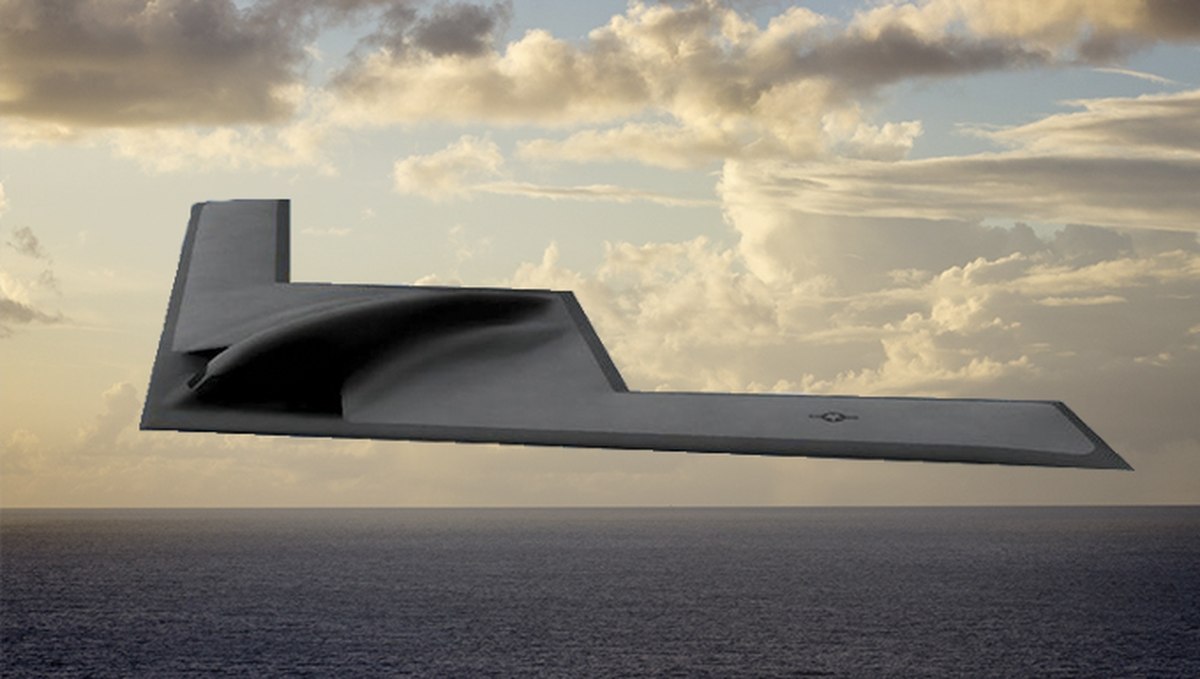

CSBA argues that none of the Air Force’s legacy aircraft — not the B-52, not the B-1, not the MQ-9, not the older fighters — are optimized for this emerging threat environment. The B-21 Raider, under development by Northrop Grumman, will likely be the first platform that can survive and operate inside such contested airspace.

The bomber force — the tip of the spear

As China and Russia continue deploying long-range missile systems and advanced radar networks, the U.S. must rely heavily on penetrating bombers capable of slipping past early-warning sensors. These aircraft would be responsible for destroying air defenses, striking command nodes, and taking out key infrastructure — actions that pave the way for fighters, tankers, and ISR aircraft to operate safely.

But CSBA warns that the planned 100 B-21 Raiders will not be sufficient for a major conflict against a technologically advanced nation. Instead, their study recommends a future force of 288 B-21s, forming the backbone of America’s long-range strike capability.

They argue that if production ramps up to 10–20 aircraft per year by the late 2020s, the Air Force could field at least 55 B-21s by 2030, improving readiness and providing enough penetrating strike power to shape the early days of a conflict.

Meanwhile, the Air Force should keep its B-52s and B-2s operational until the B-21 fleet becomes large enough, while gradually retiring the B-1 Lancer as sustainment costs rise.

The fighter force — building air superiority for the next era

A key question shaping the Air Force’s future is whether to buy Boeing’s F-15X. The CSBA study, however, offers a clear and direct recommendation: do not divert funds to new F-15s. Although the F-15X would be a strong “fourth-generation-plus” aircraft, its survivability in the heavily contested airspace of the future is doubtful. According to CSBA, buying more F-15s risks consuming budget resources that should instead accelerate the development of the next-generation air-superiority system.

The study prioritizes shifting investment toward the Penetrating Counter Air (PCA) program — a classified sixth-generation fighter concept designed to operate deep inside enemy territory and dismantle advanced air defenses. PCA isn’t just a single aircraft; it is envisioned as a family of systems, combining manned platforms, unmanned escorts, advanced sensors, and networked weapons to push into spaces where current fighters cannot survive.

To maintain momentum, CSBA recommends that the Air Force immediately increase F-35A production to 70 aircraft per year, ensuring that the fighter force evolves quickly enough to replace aging legacy platforms. While the F-35 is not a perfect aircraft, its stealth characteristics and sensor suite make it the most capable fighter in large-scale production today — a necessary bridge to the PCA era.

The study also highlights the need to modernize the F-22 Raptor and the F-15E Strike Eagle so they can remain viable in the 2030s. Meanwhile, retirement of the F-16 fleet should coincide with the arrival of additional F-35s, allowing the Air Force to streamline its mix of fighters and reduce maintenance complexity.

As for the A-10 Warthog, CSBA supports keeping six squadrons into the 2030s but strongly advises against designing a specialized replacement. Because next-generation fighters and drones will already be capable of precision air-to-ground missions, creating a new single-purpose close-air-support aircraft would be redundant. In future wars — especially those involving China or Russia — survivability and adaptability will matter far more than niche specialization.

The tanker force — the Air Force’s most fragile lifeline

The Air Force’s tanker fleet is both indispensable and dangerously outdated. With an average age of 53 years, the current inventory cannot realistically support the long-range operations likely to define tomorrow’s conflicts. Without tankers, fighters, bombers, and drones lose the ability to reach strategic distances or maintain persistence over the battlespace.

CSBA stresses the need to continue acquiring Boeing’s KC-46 Pegasus, which must eventually replace both the KC-10 Extender and the oldest KC-135 Stratotankers. By 2030, the study envisions a fleet of roughly:

• All KC-10s retired

• ~50 KC-135s retired

• 179 KC-46s in service

This plan yields approximately 520 tankers, a number large enough to sustain global operations but still short of the 630-aircraft future force CSBA ultimately recommends.

However, meeting that higher goal will require radical innovation. CSBA proposes that the next generation of tankers should be a distributed family of systems, consisting of:

• Large manned tankers (like KC-46) stationed safely outside contested regions

• Small unmanned tankers or optionally manned drones operating closer to enemy territory

• Numerous “offload points” created by these drones to extend the range of fighters and bombers

Such a model would reduce vulnerability. Instead of relying on a small number of large, easy-to-target tankers, a dispersed network of smaller nodes would make U.S. aircraft harder to disrupt. These drone tankers could even venture into lower-threat areas inside contested regions, providing fuel without putting aircrews at risk.

Future ISR and light-strike drones — building the unmanned backbone

By 2030, the MQ-9 Reaper will still be flying, but its role will change significantly. In high-end conflicts, slow, non-stealthy drones won’t survive over enemy territory. CSBA imagines the Reaper being repurposed for homeland defense, base security, and missions in permissive environments rather than deep-penetration combat.

The true deficiency lies in a mission the U.S. currently cannot perform: stealthy unmanned strike and reconnaissance inside contested airspace. To close this gap, CSBA calls for urgent development of a new aircraft concept known as MQ-X — a stealth combat UAV capable of:

• Penetrating heavily defended airspace

• Executing strikes on mobile targets

• Conducting electronic warfare

• Operating in coordinated teams with manned fighters and bombers

• Performing defensive counter-air missions

Congress canceled several promising UCAV programs in earlier years, including the Navy’s UCLASS program (later re-shaped into the MQ-25 tanker drone). CSBA argues that these abandoned efforts demonstrate the technological groundwork already exists — it simply needs to be revived and pushed into production.

The study proposes a future force of 68 MQ-X aircraft, with as many as 40 entering service around 2030 if development begins immediately. These drones would fill one of the Air Force’s most pressing operational gaps, enabling it to threaten enemy defenses without exposing pilots to danger.

Additionally, the report introduces a supplementary family of drones, the MM-UAS (multimission UAV systems), envisioned to operate in permissive or lightly contested airspace. They could:

• Provide surveillance

• Conduct targeted strikes

• Serve as communication relays

• Support ground forces in remote areas

These multimission drones would eventually replace a large portion of today’s medium-altitude UAV inventory.

The ISR and BMC2 force — the most dramatic transformation

Of all the mission areas examined by CSBA, none requires deeper transformation than intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and battle-management command and control (BMC2). In an era when China and Russia deploy long-range anti-aircraft missiles and powerful electronic-warfare tools, large traditional ISR aircraft are simply too vulnerable to fly near contested airspace.

CSBA proposes a layered transition extending into the 2030s and 2040s:

• The U-2 Dragon Lady, RQ-4 Global Hawk, and E-3 AWACS should remain in service until successors are ready.

• The RC-135 Rivet Joint, Cobra Ball, and related variants can continue into the 2040s due to their unique intelligence roles.

• The E-8C JSTARS should be retired by the mid-2020s, but only after other assets and networks are ready to cover its missions.

The centerpiece of the new ISR ecosystem is the Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) — a disaggregated constellation of sensors, aircraft, and communication links designed to survive in highly contested environments. CSBA recommends a future inventory of 21 ABMS nodes, each contributing data to a larger battlefield network.

However, the most dramatic divergence between CSBA and the Air Force lies in the call for a penetrating ISR aircraft, or P-ISR — an unmanned, stealthy platform designed to slip past enemy defenses and gather intelligence where no current aircraft can safely go.

The Air Force has no such program publicly planned, but CSBA argues it is essential. A P-ISR platform would:

• Track mobile missile launchers and armored vehicles

• Identify and monitor enemy air-defense systems

• Support long-range strikes by providing real-time targeting

• Survive inside contested airspace without risking human lives

Such a capability would fundamentally reshape how the U.S. fights in Europe or the Indo-Pacific. In war games involving Russia, mobile artillery and armored formations often move too quickly for existing ISR platforms to track. A P-ISR aircraft would fill that gap, enabling rapid targeting and interception.

Persistent, penetrating ISR is really the thread that ties the whole future force together. If the Air Force can’t quietly find, track and re-locate mobile systems inside heavily defended airspace, everything else — bombers, fighters, even tankers — is forced to operate farther away, fire more expensive standoff weapons, and repeat strikes on targets that keep moving. A stealthy P-ISR drone that can stay on station for hours, quietly mapping air defenses, missile batteries and maneuvering ground forces, gives commanders a reliable picture instead of a fuzzy snapshot. That means fewer wasted sorties, better timing for strikes and much faster kill chains when something dangerous appears, moves, or tries to hide.

There’s also a survivability angle that often gets less attention. Every time the U.S. sends a large, manned ISR aircraft near a contested border — think big jets like the RC-135 or E-3 — it risks a high-profile incident if that aircraft gets harassed or shot down. A dedicated P-ISR drone changes that calculus. It still has to be protected and used carefully, but it can fly riskier profiles, push deeper into dangerous airspace and soak up more electronic and radar emissions without putting a large crew at stake. In a crisis around the Baltics, Taiwan or the South China Sea, that difference between “we think we know” and “we have a continuously updated picture” could decide whether the U.S. reacts in time or gets surprised.

At the same time, ISR and battle management are shifting away from a few big, vulnerable platforms toward a web of smaller, cooperating sensors. Instead of relying on a handful of iconic aircraft to do everything — one for ground moving-target tracking, one for air early warning, one for signals intelligence — the future mix looks more like a mesh network. Data might come from stealthy drones, survivable manned aircraft, satellites, passive ground receivers and even fighters or bombers acting as temporary sensor nodes. A system like the Advanced Battle Management System is meant to pull all of that together so the closest shooter, not just the most traditional platform, can act first with the best information.

Put all of these pieces next to each other and the shape of the Air Force CSBA is describing starts to make sense. Heavy, stealthy bombers like the B-21 sit at the heart of the force, punching open corridors through dense air defenses and hitting hardened, high-value targets. A new generation of penetrating fighters — the PCA family — works with F-22s and F-35s to gain and hold air superiority, escorting bombers and hunting down enemy aircraft, radars and jammers. A more flexible tanker architecture, mixing big crewed aircraft with smaller unmanned refuelers, stretches that entire force far enough to operate over the Pacific or deep inside Eurasia without constantly falling back to distant bases.

Around that core, a tiered drone fleet takes on more of the dangerous and relentless work. Stealthy UCAVs like the proposed MQ-X fly alongside manned fighters and bombers, adding extra missiles, jammers or sensors without adding more pilots. Multimission UAS handle long-endurance patrol, base and homeland defense, and lower-end strike tasks in permissive airspace. Penetrating ISR drones weave through defended areas, updating the picture and keeping the whole network from going blind. Legacy aircraft — F-15Es, F-22s, some A-10s, classic bombers and current ISR platforms — remain in the mix, but increasingly as part of a broader ecosystem instead of the main event.

None of this comes cheaply, and CSBA’s force is not just a shopping list of new airframes. It assumes major investments in things like secure data links, hardened and distributed command centers, resilient space support, cyber defenses and realistic training environments where crews and algorithms can practice against dense, modern air defenses. It also implies hard choices: retiring older aircraft earlier than some would like, resisting the urge to buy upgraded but non-survivable designs, and accepting that nearly every future combat platform will need to be multi-role and networked from day one.

Still, the logic behind the study is straightforward. If the United States wants an Air Force that can credibly fight one great-power war and still have enough strength left to deter another, it needs more than incremental upgrades and a handful of new jets. It needs a fleet built around range, stealth, payload, sensing and connectivity — from bombers and fighters down to tankers and drones — specifically tailored for highly contested skies over Europe and the Pacific. The aircraft outlined in this vision are less about prestige and more about buying time and space: time to see a threat developing, space to maneuver and respond, and enough survivable punch to convince any potential rival that starting that kind of war would be a very bad idea.