Science fiction has always loved its ships, but not just as vehicles that move characters from one place to another. The best sci-fi spacecraft feel like ideas made solid — expressions of fear, hope, ambition, and ego, all wrapped in metal, glass, and impossible technology. Long before audiences cared about technical specifications or power rankings, these ships existed to set a mood, define a universe, and quietly tell us what kind of story we were stepping into.

Some of these designs are massive and intimidating, built to loom over planets and remind viewers how small humanity can be. Others are modest, even fragile, yet loaded with emotional weight, carrying a single life, a last chance, or an entire civilization’s future. What makes them memorable isn’t how fast they travel or how many weapons they carry, but how perfectly they fit the world around them. A good sci-fi ship feels inevitable, as if no other design could possibly belong in that story.

This collection looks past the usual debates and surface-level trivia to focus on creativity. These are ships that stand out because of the ideas behind them, the roles they play, and the way they linger in the imagination long after the screen fades to black. Some are iconic, some are unexpected, and a few might even make you pause and wonder why they don’t get talked about more often. Together, they show that in science fiction, the most interesting journeys often begin with the ship itself.

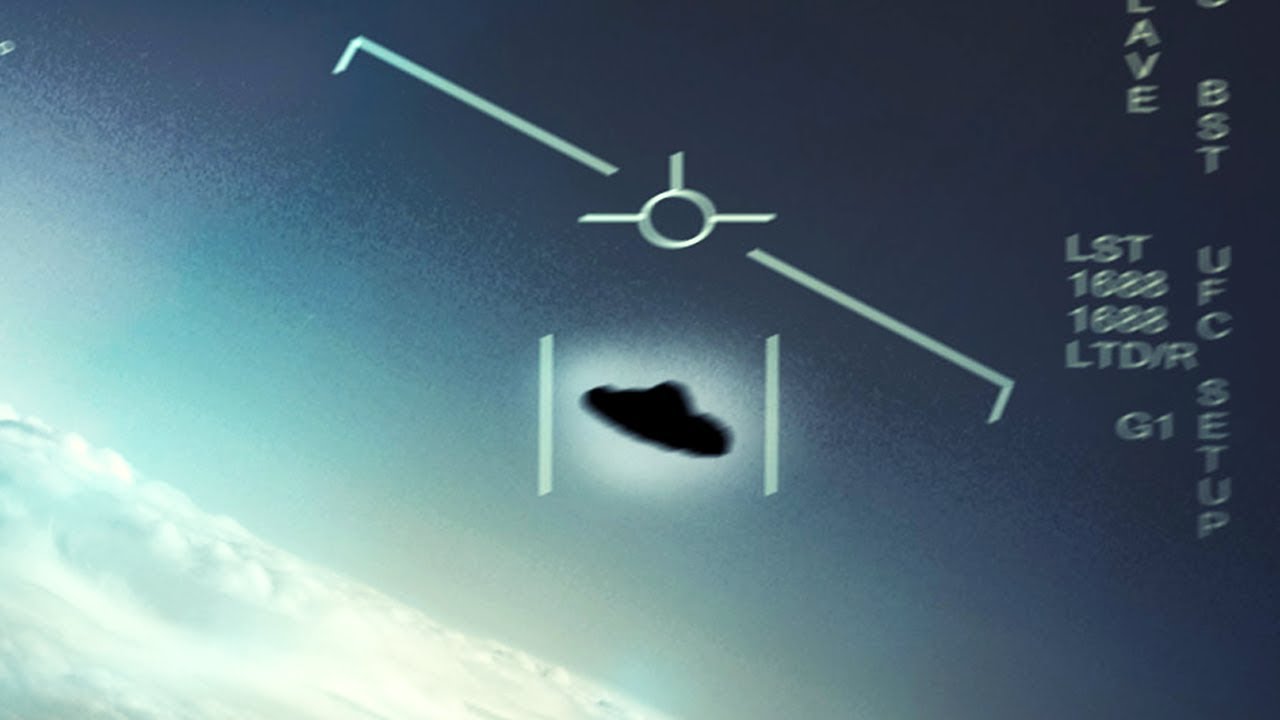

The Most Famous Spaceships in Sci-Fi Movies and TV

UNSC Infinity (Halo franchise)

If you had to sum up the UNSC Infinity in one sentence, it would be: a ship built for a universe that refuses to play fair. It’s gorgeous in that clean, intimidating “military future” way—like an aircraft carrier that got promoted into space and then given an entire research city to carry around.

Infinity isn’t just about raw power, either. It’s a survival machine. It can move at normal sublight speeds for local operations, but it’s also built to make bigger jumps when it needs to, which matters in a setting where getting out of trouble isn’t a luxury—it’s the difference between “mission complete” and “everyone becomes space dust.”

Then there’s the part people forget: ships like this aren’t only weapons. They’re homes. Infinity is basically a traveling community, with onboard spaces designed to keep humans sane for the long haul. The idea of a biosphere onboard isn’t just a flex; it’s psychological life support. Same with the bar, the hangout spots, the little comforts that keep a crew from feeling like they live inside a metal shoebox during a war.

And the communications side is a quiet kind of superpower. In a galaxy where distance is often the biggest enemy, being able to coordinate and stay connected across huge stretches of space can matter as much as any cannon. Infinity feels like the closest thing to a “vacation ship” you’ll ever see… if the universe wasn’t constantly trying to eat you.

TARDIS (Time And Relative Dimension In Space)

The TARDIS is the ultimate trick ship, because it looks like it shouldn’t even qualify as one. A little box. A phone booth vibe. Something you’d walk past without a second glance—until you step inside and your brain quietly panics.

“It’s bigger on the inside” is one of those lines that became a meme, but it’s also a perfect summary of why the TARDIS stays iconic: it turns space itself into a punchline. The interior isn’t just roomy; it’s absurdly vast, and it shifts tone depending on the Doctor, the era, and the mood of the story. It can feel like a cathedral, a machine room, a labyrinth, or a comforting mess of friendly chaos.

What makes the TARDIS special isn’t just time travel. Plenty of stories do time travel. The TARDIS makes time and space feel… casual. Like taking a wrong turn down an alley and accidentally landing in a different century. It’s a narrative tool that allows the show to jump from tragedy to comedy to cosmic horror in a heartbeat.

And it’s tougher than it looks. It’s not fragile sci-fi glass. The TARDIS can take impacts, survive ridiculous situations, and keep functioning in conditions that would shred more conventional ships. The few things that truly endanger it aren’t random weapons—they’re usually things that mess with reality itself, or other TARDIS-level phenomena. Basically, the only thing that consistently threatens the TARDIS is something that plays at the same tier of weird.

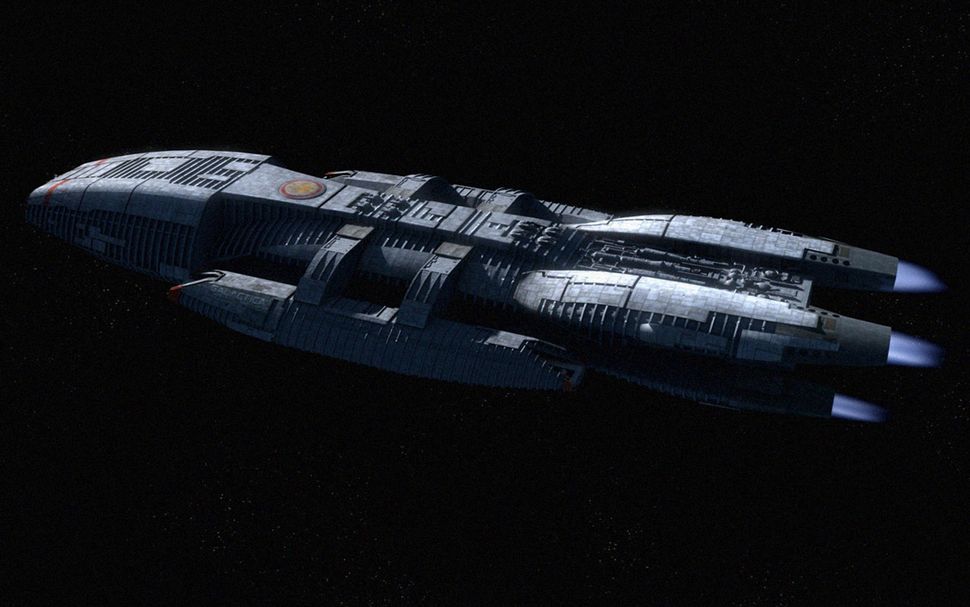

Battlestar Galactica (Battlestar Galactica series)

Battlestar Galactica has a kind of ugly beauty. It’s not sleek. It doesn’t feel like it was designed to win a style contest. It looks like it was built to survive, and then forced to keep surviving long after anyone would reasonably expect it to.

One of the coolest things about Galactica is that its limitations are part of its identity. It’s not the most modern ship in its universe, and it takes damage—real, meaningful damage. It’s the opposite of a pristine “reset button” spaceship. When it gets hurt, you feel it. When systems fail, it becomes a story problem, not background noise.

And yet it’s clever. It adapts. It finds workarounds. In moments where something goes wrong with its networked systems or a digital threat creeps in, the ship’s older design can actually become an advantage. It’s like the sci-fi version of a person who still owns a flip phone and therefore can’t be hacked in the same way everyone else can.

The faster-than-light jumps are also a big deal, because they aren’t just “hit warp and escape.” They’re choices with consequences. Every jump becomes strategy, desperation, and hope all tangled together. Galactica earns its legend not by being invincible, but by refusing to quit.

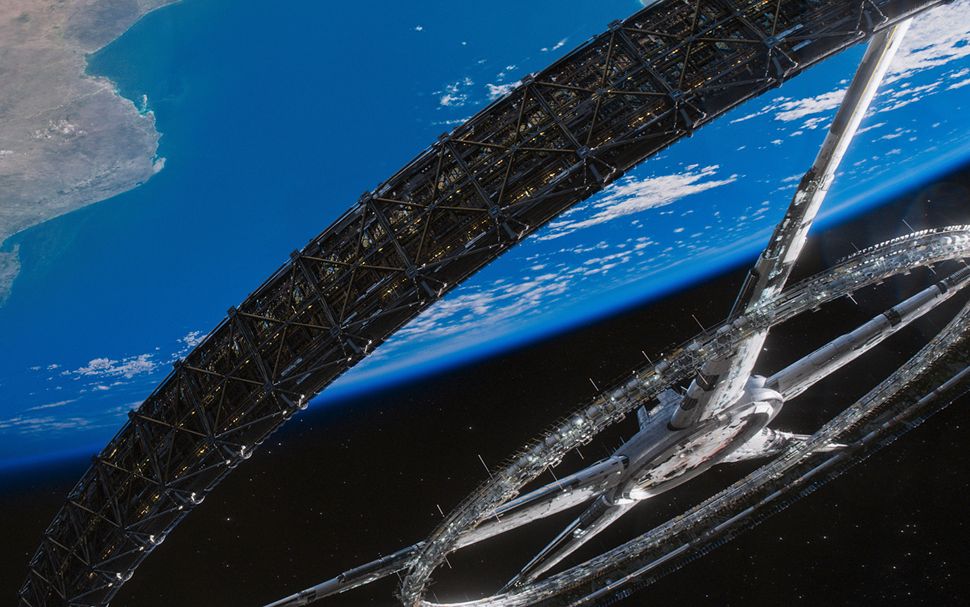

Elysium Station (Elysium)

Elysium’s “ship” is really a space station, but it’s so engineered and self-contained that it feels like a world pretending to be a vessel. It’s one of the most chillingly realistic sci-fi ideas: not a space utopia for everyone, but a gated paradise that exists specifically to keep the “right” people away from the mess.

Visually, it’s a flex. The greenery, the open spaces, the clean architecture—it’s Earth’s best parts curated and locked behind an invisible rope line. That’s what makes it so striking: it’s not alien. It’s familiar, and that familiarity makes it feel like something humans would actually build if they had the money and the fear.

The technology on Elysium isn’t just about lasers or engines. It’s about comfort and control: medical systems that feel miraculous, security infrastructure that feels inevitable, and automation that quietly reinforces inequality. Even the idea that it can dispatch rescue ships once you’re a registered citizen is a brutal little detail. It implies the system can save lives easily… it just chooses when and for whom.

As a piece of sci-fi ship design, Elysium wins by being believable. It’s not magical. It’s horrifying because it makes you think, “Yeah… people might absolutely do this.”

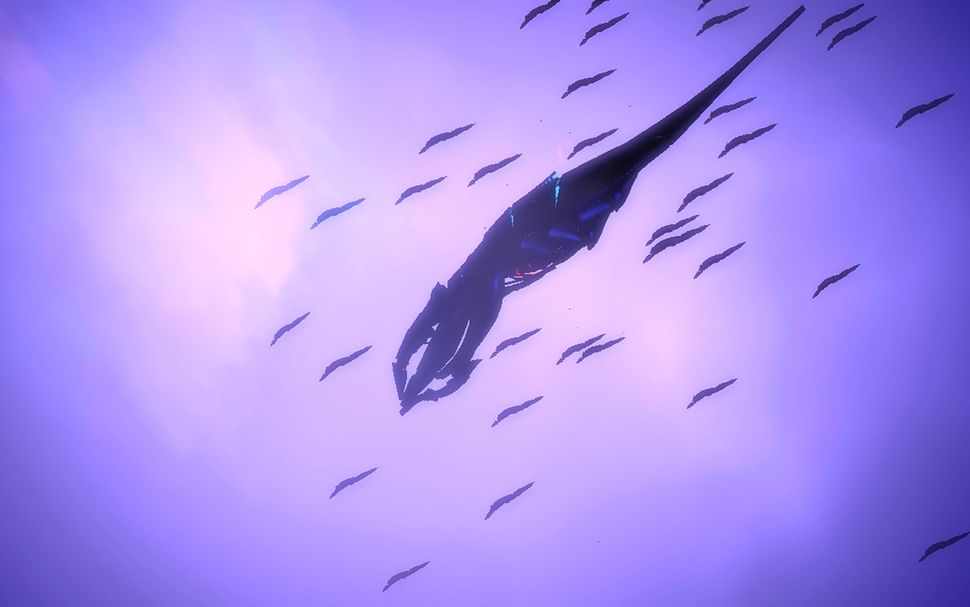

Reapers (Mass Effect franchise)

The Reapers aren’t just ships. They’re a species that happens to come in ship form, which is already a wild design choice. They fuse biology and machinery so seamlessly that it stops feeling like “organic inside metal” and starts feeling like a single, unified thing—alive in a way that regular spacecraft aren’t.

What makes them especially unsettling is their patience. These aren’t villains who rush in with fireworks. They wait. They hide in the cold gaps between galaxies for stretches of time that make human history feel like a weekend. That scale changes the whole vibe: the Reapers don’t feel like an enemy you can outsmart in the short term. They feel like an inevitability.

And then there’s the deeper twist: their influence is built into the galaxy’s infrastructure. The mass relay network that everyone uses to travel quickly? That’s part of the Reapers’ legacy. The Citadel itself? Also tied into their design. That means the “normal” way the galaxy functions might be built on the foundations of something hostile, like a city whose roads were designed by a predator who understands traffic patterns better than you do.

As far as sci-fi “ships” go, Reapers are brilliant because they flip the script. They aren’t just vehicles. They’re a cosmic trap with engines.

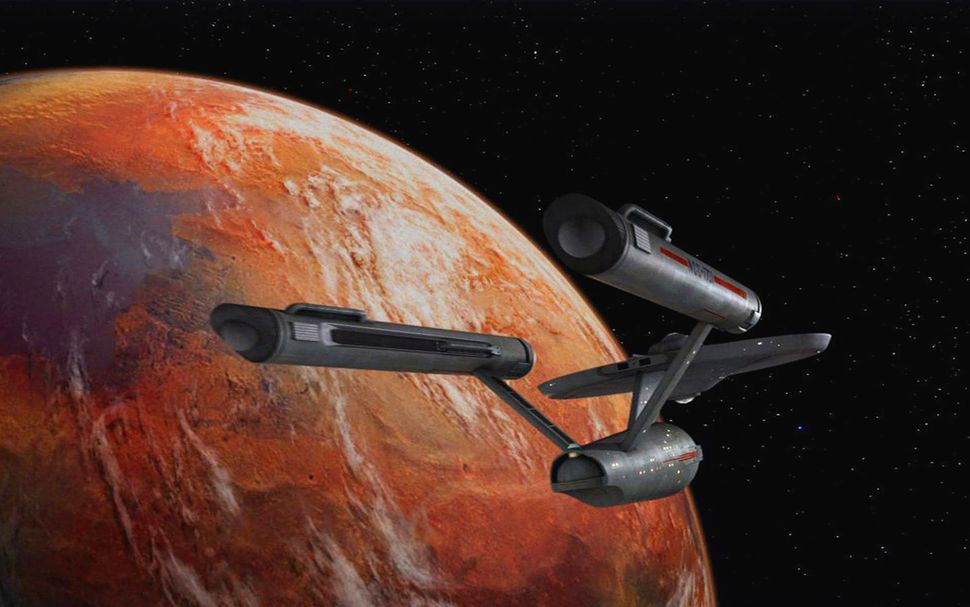

USS Enterprise Line (Star Trek franchise)

Arguing which Enterprise is best is basically a hobby at this point, but the more interesting thing is what the Enterprise represents as a ship line: exploration with teeth. It’s not a pure warship, not a pure science vessel, and not a luxury cruise liner (even if some episodes kind of treat it like one). It’s a multi-role symbol of a future that believes curiosity is worth the risk.

Across its variations, the Enterprise tends to push limits—sometimes responsibly, sometimes in the exact way that makes engineers sigh. It’s the ship that does “impossible” routinely: handling extreme environments, surviving scenarios where physics feels optional, and pulling off maneuvers that feel like they should void the warranty immediately.

Some versions introduce clever modular ideas—splitting into separate sections, reconfiguring for different mission needs, and generally being built like a Swiss Army knife in space. The Enterprise is also often portrayed as a ship where human factors matter: command decisions, teamwork, and ethics. It’s not just engines and shields—it’s the stage for the Federation’s values.

That’s why the Enterprise stays “great.” It’s the rare famous spaceship that’s iconic not only because of what it can do, but because of what it chooses to do.

Death Star and Starkiller Base (Star Wars franchise)

Let’s be honest: these aren’t “practical ships.” They’re architectural threats. They exist to make a point, and the point is: don’t even try.

The Death Star is basically fear turned into engineering. It’s so big it gets compared to a moon, and that’s not just a metaphor—it’s a design strategy. If something looks like a celestial body, it changes how you think about it. It stops being “a target” and starts being “a fact.”

The weapon itself is the obvious headline—planet-killing power is hard to ignore—but what’s almost as scary is the logistical implication. This is a station that has to feed, house, and command an enormous population. It’s a floating government, military base, prison, and factory all at once.

Starkiller Base takes the idea and turns the knob to ridiculous, leaning into mysterious energy concepts and “how is that even possible” physics. It’s a sci-fi escalation symbol: when the story wants to show that evil has leveled up, it builds a bigger shadow.

They rank below more agile ships in terms of survivability (because yes, people keep finding ways to blow them up), but in terms of sheer “weaponized monument” design, they’re hard to beat.

Ha’tak (Stargate franchise)

Ha’taks look like pyramids drifting through space, which is such a bold aesthetic choice that it almost dares you to laugh—until you realize how dangerous they are. Stargate ships often blend myth and sci-fi, and the Ha’tak is basically that idea crystallized: ancient iconography with terrifying capability.

In-universe, they’re fast enough to be a serious interstellar presence, and their defenses are the real “oh no” feature. Shields that can withstand extreme stellar environments for long periods tell you these aren’t fragile cruisers. They’re built to endure punishment.

Some variants carry cloaking tech, which adds a nasty layer of uncertainty. Even if cloaking isn’t standard across the fleet, the mere possibility changes every tactical calculation. It’s the difference between “we see them coming” and “we only notice when everything starts exploding.”

What’s fun about Ha’taks is that they communicate power immediately. You don’t need a technical manual. You see one, you understand the message: a god-king just arrived, and negotiation is optional.

Event Horizon (Event Horizon)

Event Horizon is the kind of spaceship that makes you wish engineers in horror movies had a stronger “maybe don’t” instinct. As a concept, it’s an experiment: a ship with an engine meant to leap across vast distances by manipulating space-time itself. As a story object, it’s a warning label.

The scariest part isn’t just what the ship can do—it’s what it implies. If an engine can punch a hole through space-time, you’re not just traveling. You’re opening doors. And the universe has a habit of having things behind doors that you didn’t invite.

The film uses Event Horizon like a haunted house in space, but the ship’s “innovation” is what fuels the fear. It’s a sci-fi nightmare that says: maybe the frontier isn’t empty. Maybe the math works, but the destination is wrong.

Even in broken-down, half-understood form, the ship feels powerful. The idea that it can generate black holes isn’t just cool-sounding—it’s a way of telling you the scale of forces involved. This isn’t warp drive. This is reality being bent until it screams.

Independence Day Mothership (Independence Day)

The Independence Day mothership is big in a way that almost stops being comprehensible. Hundreds of kilometers long isn’t “large ship” territory—it’s “map feature” territory. It’s the kind of object you’d measure the way you measure geography.

What makes it memorable isn’t just size, though. It’s the sense of industrial alien purpose. Inside, the tunnels and internal structure feel like a hive—organized for movement, logistics, and control. The imagery suggests a civilization that doesn’t just travel; it consumes.

A detail that sticks is how eerie the interior feels. That blue mist, the strange atmosphere, the sense that humans are walking through a space not designed for them. The ship doesn’t need to show off with clever dialogue or glowing dashboards. Its design communicates: you are not in charge here.

And the mothership’s mystery helps it. We don’t know everything it can do, which keeps it scary. Sometimes the most terrifying ships aren’t the ones with the longest spec sheet—they’re the ones where you suspect the spec sheet wouldn’t make you feel better anyway.

USCSS Prometheus (Prometheus)

Prometheus is the “corporate space exploration” dream: sleek, expensive, and built like someone signed a blank check. It’s designed for long-distance missions with humans who need to sleep through huge chunks of travel, wake up functional, and then immediately start poking at dangerous mysteries on strange worlds (because that always ends well).

The ship is packed with comforts and mission support gear—hypersleep chambers, exploration vehicles, escape options, and communications systems meant to keep it connected across enormous distances. It feels like a blend of science vessel and luxury expedition, which fits the tone: it’s not a scrappy crew barely surviving, it’s a funded mission with confidence bordering on arrogance.

One of the most interesting design notes is vertical takeoff and landing capability. For a ship of its size, that’s a big deal. It implies a level of control and thrust management that goes beyond “land in orbit and send a shuttle.” Prometheus wants to put boots and machines on the ground directly, fast.

Of course, the darker irony is that all the engineering brilliance in the world doesn’t save you from bad decisions. Prometheus is a gorgeous ship that highlights a classic sci-fi truth: technology can get you to the horror, but it can’t always get you out.

The Rocinante (The Expanse franchise)

The Rocinante is what happens when a ship is built with the assumption that physics still matters. It’s a warship, but it’s also a home, and it’s designed with human bodies in mind. That detail alone makes it stand out: the designers care about the fact that constant acceleration and g-forces can wreck people if you don’t plan for it.

Roci has the vibe of a tough, dependable machine—fast, capable, and adaptable. It can fight, it can run, it can chase, it can survive. It’s not the biggest ship in its universe, but it’s the kind of ship that wins by being used well. A skilled crew in the Rocinante feels dangerous, not because the ship is magic, but because it’s efficient.

It also nails that “lived-in” feeling. This isn’t a floating showroom. It’s a place where people argue, plan, sleep badly, patch damage, and keep going. That’s a big part of why fans love it: it feels like a real ship you could actually inhabit, with real consequences, not a shiny fantasy cruiser.

[Jeff Bezos Saves “The Expanse”]

Heart of Gold (Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy franchise)

The Heart of Gold is the sci-fi equivalent of someone looking at the rules of travel and saying, “No thanks, I’ll take the loophole.” The Infinite Improbability Drive is one of the funniest and most creative propulsion ideas ever, because it treats the universe like a cosmic prank: if you can make the impossible sufficiently likely, you can arrive anywhere instantly.

What makes it great isn’t only the engine gimmick. It’s the ship’s personality. It’s built with creature comforts and absurd charm in mind, like doors that announce how happy they are to help you. That’s such a small detail, but it tells you everything: this is a future where even the interface design has a sense of humor (or at least a willingness to irritate you politely).

Design-wise, the ship often appears clean and bright, almost sterile, which makes it feel more surreal. It’s not grimy space trucking. It’s a weird, pristine bubble drifting through chaos, carrying characters who are constantly one step away from existential confusion.

The Heart of Gold is iconic because it makes sci-fi feel playful without losing its big ideas. It’s ridiculous, but it’s smart ridiculous.

Icarus II (Sunshine)

Icarus II earns its place here because it’s built around a single desperate mission: carry an enormous payload toward the sun in hopes of fixing a dying situation back home. That premise alone forces the ship design into uncomfortable territory. This isn’t exploration. This is survival under pressure, and the ship has to function in an environment that’s basically a slow-cooking cosmic furnace.

The ship’s engineering is about endurance—systems that keep working even when things go wrong, even when the crew is exhausted, even when the mission gets compromised by human conflict and fear. There’s a stubborn reliability to it, like the ship was designed with the assumption that someone will make mistakes, and it still needs to keep running.

What’s especially compelling is the way the ship interacts with the sun. Light becomes a threat, heat becomes an enemy, and every choice is measured against exposure. That’s a cool reversal from a lot of sci-fi, where space is mostly cold emptiness. Here, the danger is overwhelming brightness.

Icarus II feels heroic in a grounded way. It’s not flashy. It’s a vessel built for an impossible job, and it keeps pushing forward because turning back isn’t an option.

Superman’s Pod (Kal-El’s Ship)

Superman’s spaceship is one of those designs that raises more questions the longer you think about it—and that’s half the fun. It’s small, simple-looking, and totally focused on one job: deliver a living infant across interstellar distance and keep him alive long enough to arrive.

That sounds straightforward until you consider the details. How did it manage life support for a baby? Feeding, temperature regulation, hygiene, comfort, stimulation—infants aren’t exactly “set it and forget it” cargo. The pod implies Kryptonian automation that’s so advanced it borders on magical. It’s like a miniature caretaker system wrapped in a spacecraft shell.

Then there’s navigation. Sending a pod across deep space isn’t like tossing a bottle into the ocean. It suggests precise targeting, predictive astrogation, and probably a level of control over long-duration travel that humans in most sci-fi stories can only dream about.

The most interesting part might be its compactness. The ship doesn’t look like it should contain everything it needs, which hints at Kryptonian tech being far more space-efficient than our imagination usually allows. It’s a simple design that quietly screams, “These people were on another level.”

The Resolute (Lost in Space)

The Resolute is the kind of ship that looks impressive at first glance: big, capable, and designed to carry people—including families—which immediately makes it different from most “crew of professionals only” sci-fi ships. It suggests colonization ambitions, not just exploration. It’s a moving bridge between Earth and somewhere else.

But it’s also a ship that feels… vulnerable. The story highlights how a small, intelligent threat can cause disproportionate damage, which makes you question how robust the systems really are. If one hostile presence can disrupt operations so badly, what does that say about redundancy, security, and failure planning?

The ship’s relationship with surface craft is another interesting limitation. If it struggles to reliably retrieve smaller transport ships without a strong enough signal, that raises practical questions. In any realistic colonization or rescue scenario, your “pickup” reliability is a big deal. Away missions aren’t just action scenes—they’re logistics.

Still, the Resolute has a strong concept at its core: a large, community-oriented ship meant to move humanity outward. Even its flaws make it more believable. It feels like a human-built project—ambitious, impressive, and not as invincible as the brochure promised.

E.T.’s Spaceship (E.T.)

E.T.’s ship is iconic precisely because we barely see it. It’s like a glimpse of a much bigger world that the movie refuses to fully explain, which makes it feel more authentic. Real encounters with something truly alien probably wouldn’t come with a tour guide and a technical breakdown.

What we do get is a sense of gentle purpose. The ship isn’t a war machine. It’s a transport for visitors—botanists, explorers, curious beings who treat Earth like a strange garden worth studying. That alone makes it stand out in a genre that often defaults to invasion.

The shape has a whimsical quality, almost balloon-like, which adds to the story’s tone. It feels designed by a culture with different aesthetic instincts than ours. Not everything needs to look aerodynamic by human standards. Not everything needs to look intimidating. Sometimes the most alien thing is softness.

And that’s the magic: this ship suggests advanced travel tech without making it loud. It arrives, it does what it needs to do, and it leaves—like a quiet door opening and closing between worlds.

District 9 Mothership (District 9)

The District 9 mothership is one of the most haunting “hovering presence” ships ever put on screen. It doesn’t zoom around in flashy battles. It just hangs there above the city, enormous and still, like a permanent bruise on the sky.

What makes it so memorable is how little we understand it. The ship is clearly capable of tremendous power, but it’s also clearly not functioning properly. Its inhabitants are in crisis—starving, disorganized, stranded. That contrast makes the mothership feel tragic and unsettling at the same time. It’s a symbol of technological superiority… and collapse.

The remote activation idea is a fascinating detail. It implies the ship can respond to its rightful operators even after long dormancy, like it’s waiting for a key. That adds tension, because it means the ship’s “off” state might be temporary, and the moment it powers back up, everything changes.

As a design, it’s brilliant because it’s not a clean sci-fi fantasy. It looks heavy, industrial, and worn. It feels like something that has history—and problems.

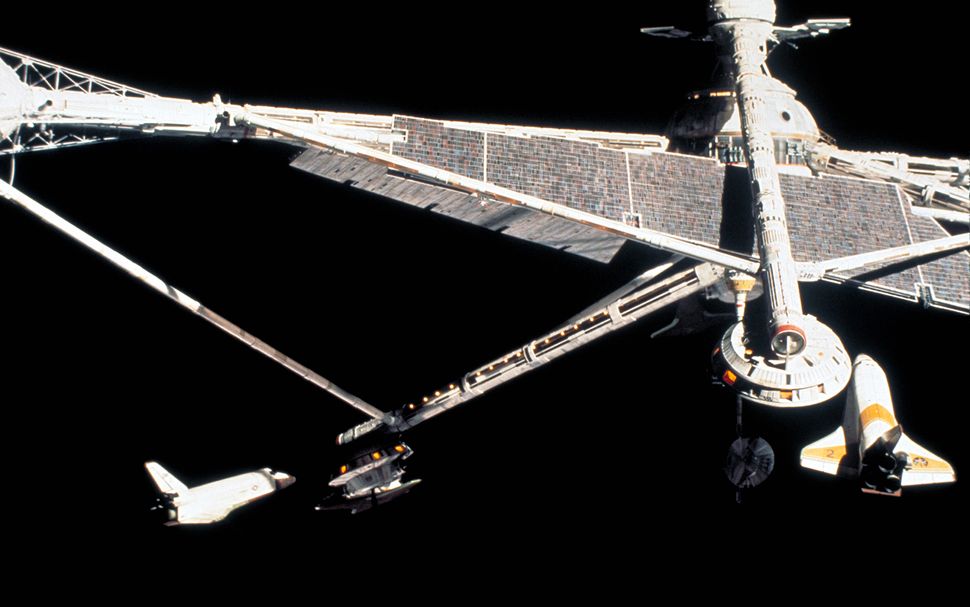

The Hermes (The Martian)

Hermes is a great example of a ship that feels like a real near-future interplanetary vehicle—still futuristic, but not magical. It’s built around long-duration travel between planets, with rotating sections (or similar design thinking) meant to keep humans functional, and systems designed for reliability rather than flashy combat.

One of the most interesting points is how the story treats Hermes as something that can be modified mid-mission. It’s not a sacred object you’re forbidden to touch. The crew can dig into systems, reroute plans, and change its trajectory when everything is on the line. That makes it feel like an engineered tool rather than a plot-protected monument.

Hermes also earns respect through resilience. It takes on more than it was originally designed for, and it keeps working. That’s the kind of “heroism” real spacecraft have: not winning fights, but enduring. It’s a ship that survives stress, pressure, improvisation, and insane mission updates.

Even the idea of using onboard explosives as part of a maneuver shows the story’s willingness to treat space travel as dangerous engineering. It’s not elegant. It’s “this might work, and we might die.” That’s why Hermes sticks with people—it feels earned.

Superman’s Spaceship

There’s something weirdly charming about the fact that Superman’s ship remains partly a mystery even after decades of stories. It’s not shown as a detailed, comprehensively explained machine. It’s more like a mythic artifact that happens to have brought a person to Earth.

Still, the questions it raises are fascinating. A baby traveling alone across space implies a fully automated system capable of caretaking and long-term stability. It suggests the ship can monitor vital signs, maintain a safe environment, and possibly even interact with the passenger in some comforting way. That kind of automation is beyond most sci-fi ships, which usually still rely on adult crews and constant oversight.

The ship’s small size is also telling. Kryptonian tech appears compact and efficient, like they’ve solved the “bulk problem” that so many human-designed ships struggle with. It hints at energy sources, materials science, and system integration that are far ahead of what we’d consider normal.

And the most important part is what it symbolizes: Krypton didn’t just send a baby away. They sent him with a machine that could deliver him safely to a specific new life. That’s not only engineering. That’s hope packaged as technology.

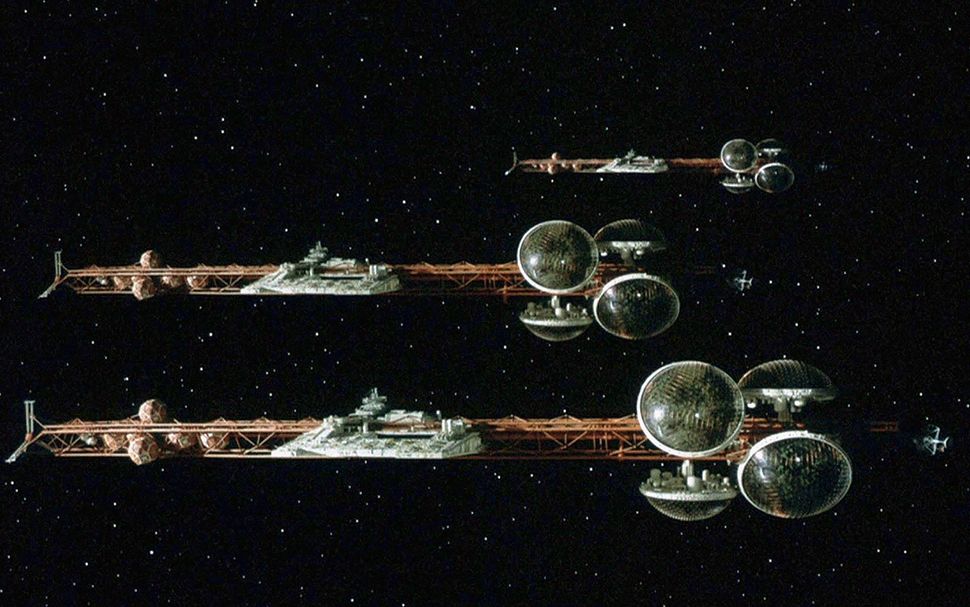

The Valley Forge (Silent Running)

The Valley Forge is one of the most emotionally loaded ships on the list because it isn’t carrying weapons or treasure—it’s carrying life. A whole ecosystem, contained and preserved, like a floating ark in a future where Earth’s natural world is gone.

Building a closed ecosystem is one of those sci-fi ideas that sounds poetic until you think about how hard it would be. Plants, animals, water cycles, air management, soil health, light requirements—everything has to be balanced, and one failure can cascade. That makes the ship feel fragile in a very human way: not “one laser shot and it explodes,” but “one long-term system imbalance and everything slowly dies.”

The forest dome idea also makes the ship visually unforgettable. It’s space industrial design wrapped around something soft and living. That contrast carries the story’s sadness and beauty at the same time.

And the light dependency is a perfect plot pressure point. Life needs energy. Without a sustained light source, even the most heroic ark becomes a drifting tomb. The Valley Forge is brilliant sci-fi because it reminds you that preserving life is harder than winning a battle.

Millennium Falcon (Star Wars franchise)

The Millennium Falcon isn’t the cleanest ship in the galaxy, and that’s exactly why it works. It’s the sci-fi equivalent of a beat-up car that somehow outruns brand-new sports models because the owner knows every quirk, every hidden trick, every part that can be coaxed into working when it really matters.

Part of the Falcon’s greatness is its contrast with sleeker ships like the Enterprise. The Falcon isn’t run by a massive crew with pristine protocols. It’s run by scrappy people who make do, improvise, and occasionally pull off miracles through stubbornness and guts.

And despite its worn look, it’s shockingly capable. It’s fast, it can fight, it can sneak into tight spaces, and it can survive bizarre environments that would kill other ships. The Falcon feels like it has personality—like it’s almost a living member of the crew. When it breaks down, it feels like a character having a bad day, not just a machine failing.

It’s also iconic because it represents a style of heroism: not the clean hero with the perfect equipment, but the messy hero who wins anyway.

[Building the Fastest Hunk of Bricks in the Galaxy (Video)]

Serenity (Firefly franchise)

Serenity is the ship you love because it’s honest. No warp drive. No sleek “future museum” vibe. It’s a working vessel with visible plumbing, real toilets, and a constant sense that something is due for repair. It’s basically a flying home for people who live on the edge of society.

The ship’s interior feels like a warehouse because it is, in spirit: practical space for cargo, for jobs, for scraping by. That gritty functionality makes Serenity believable. It’s the kind of ship people would actually use if space travel became common but wealth stayed concentrated. Not everyone gets a shiny starship. Most people get a vehicle that works… most of the time… if you baby it.

Serenity’s survival strategy isn’t “outgun the enemy.” It’s “stay unnoticed, stay moving, stay clever.” The ship’s modest profile becomes an advantage. It can slip through cracks, blend into the background, and avoid attention long enough for the crew to keep living.

And the emotional hook is strong: Serenity isn’t just transport. It’s freedom, however messy. A place where a misfit crew can belong—even when the universe doesn’t want them to.

Alien Ships in Arrival (Arrival)

Arrival’s alien ships are a masterclass in “make it unfamiliar without making it silly.” They don’t look like rockets or planes. They appear like smooth, towering forms that hover with zero visible propulsion, immediately forcing you to accept that you don’t understand the rules here.

The ships feel synchronized, too. They don’t behave like independent vehicles so much as connected nodes in a single system. When something happens around one ship, it feels like the others know. That gives them an eerie intelligence, like they’re part of a distributed mind—or at least a communication network far beyond human comprehension.

Inside, the experience gets even stranger. Gravity doesn’t behave normally, and the interior environment feels like it’s designed to reshape human perception. It’s not a friendly “welcome aboard.” It’s a controlled interface: the ship dictates how you move, how you see, and how you interact.

And that fits the theme perfectly. These ships aren’t about conquest. They’re about communication—and communication as a kind of technology. They’re beautiful because they feel purposeful, but they stay mysterious enough that you keep wondering what else they can do.

Spaceball One (Spaceballs)

Spaceball One deserves a spot here because it’s a parody ship that accidentally highlights real sci-fi ship problems other franchises glide past. The whole speed ladder—Light Speed, Ridiculous Speed, Ludicrous Speed, Plaid Speed—is funny because it points out something obvious: if you can go too fast, you can absolutely overshoot your target like a confused GPS doing its best.

The ship also pokes fun at the endless escalation of “bigger is scarier.” It’s absurdly huge, loud in its presence, and run by villains who are somehow less competent than their own machinery. That contrast is half the joke: a terrifying ship piloted by people who don’t deserve the keys.

And then there’s the transformation gag—turning into a giant maid with a vacuum that can literally suck air off a planet. It’s ridiculous, but it’s also clever satire: sci-fi superweapons are often just exaggerated versions of mundane tools. Spaceball One takes that idea and makes it literal.

It’s a ship that makes you laugh, but it also earns its place by being oddly inventive. Parody still counts as creativity—sometimes even more so, because it has to understand the original well enough to twist it.