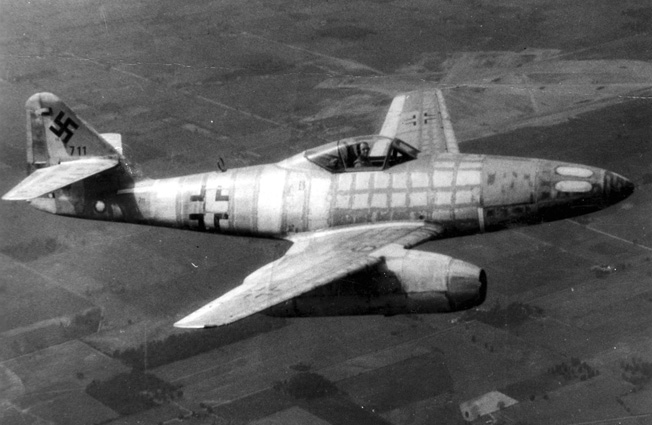

The Germans understood long before sunrise that the bombers were on their way. Even as the U.S. 457th Bomber Group gathered over the brightening sky above London, German crews were already at their flak guns and fighter strips, ready for the inevitable clash. That March operation brought together more than 1,220 Allied bombers, escorted by waves of swift P-51 Mustang fighters, all pushing toward Berlin while braving a storm of anti-aircraft fire. Cutting through this chaos were the radical Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighters, faster than anything else in the sky and armed with air-to-air rockets being used operationally for the very first time.

It became the last immense air engagement over Europe—a final, punishing showdown that cost the lives of many American airmen and pushed German pilots to their physical and psychological limits. Among those flying toward danger was Oberleutnant Gunther Wegmann, the commander of Jagdgeschwader 7’s 9th Squadron, guiding his formation of Me-262s into a wide, loose approach toward the incoming bombers. Wegmann and his wingmen unleashed their R4M rockets into a single, tightly clustered formation of roughly 60 B-17 Flying Fortresses from nearly 3,000 feet away. Dozens of rockets tore into the sky, detonating within the bomber stream and creating violent bursts of flame, fragments of metal, and spiraling debris that instantly disrupted the tight, disciplined boxes of Allied aircraft.

As soon as the rockets were spent, the German jets split up and turned for home, each pilot taking his own line back through the turbulent sky. Wegmann, however, spotted another bomber formation and instinctively banked around for a fresh attack run. Closing in from behind, he waited until he was about 600 yards out before firing his MK-108 cannons. The brief but ferocious burst shredded one bomber’s engine cowling, sending pieces of metal tumbling into the slipstream. For a moment, Wegmann felt a fierce surge of triumph and began transmitting his claim back to base.

That moment ended abruptly when incoming fire hammered his jet. Bullets slapped against the canopy, sheared instruments from their panels, and punched holes through the fuselage. His right leg suddenly felt heavy and lifeless. Reaching down, he found a deep, jagged wound just below the knee—yet the shock of adrenaline kept the pain at bay while his crippled jet streaked through the air at 18,000 feet.

He forced the damaged fighter into a steep descent. By the time he reached around 12,000 feet, flames were licking out of the starboard engine, eliminating any hope of a controlled landing. A crash would have been instant death. He pushed the nose forward, unstrapped himself, released the canopy’s retaining bolt, and was violently pulled from the cockpit at nearly 250 miles per hour. Wegmann’s body bounced hard against the tail before he dropped clear, spinning into open air. After counting several long, disorienting seconds, he pulled his parachute cord and drifted downward toward the outskirts of Wittenberge, northwest of Berlin. He brushed the tops of pine trees before managing a rough landing in a small meadow.

“German pilot!” he shouted as an older woman approached him. Luck, for once, stayed with him—she was a nurse. Quickly assessing his condition, she bound his thigh tightly and applied a tourniquet that likely saved his life. Within hours, he was transported to a hospital, though his leg could not be saved and was amputated soon after.

Not everyone escaped that day’s battle. Five American fighter pilots never returned. Sixteen bombers were torn apart by flak or ditched behind Soviet lines after limping eastward with serious damage. Another 25 bombers were destroyed outright by German aircraft—losses inflicted in exchange for only two jet fighters. Even so, the ferocity and bravery of the German jet units could not alter the overwhelming imbalance of resources. The relentless Allied advance in the air, on land, and at sea, backed by vast industrial outputs and manpower, was already closing in from all directions.

Shattering Speed and the Feeling of Power

The Me-262 left a deep impression on everyone who encountered it. As the world’s first operational turbojet fighter, it outpaced every Allied aircraft with ease. It reportedly reached around 540 miles per hour, cruised comfortably near 460, and traveled roughly 650 miles without refueling. With a service ceiling approaching 38,000 feet and a climb rate nearing 4,000 feet per minute, the jet possessed a completely different personality from piston-engine fighters. Its twin Junkers Jumo powerplants delivered nearly 2,000 pounds of thrust each, pushing the sleek aircraft into performance territory few pilots of the era had ever imagined. Its standard armament—four 30mm MK-108 cannons—gave it devastating firepower, and the Me-262 could also carry up to 1,000 pounds of bombs when configured as a fighter-bomber.

What truly transformed the jet into a nightmare for Allied bomber crews was the introduction of the R4M rocket. These compact, high-explosive projectiles allowed pilots to strike dense formations from outside the range of return fire. Leutnant Klaus Neumann, who transitioned from Me-109 and FW-190 piston fighters to jets, explained the tactic plainly: fire the rockets to tear open the formation, and then hunt down the isolated bombers struggling to stay airborne. For him, flying the Me-262 felt exhilarating—almost surreal. Compared with the machines he had flown in Russia, the jet seemed to compress distance, amplify firepower, and offer a rare sense of control in a sky filled with danger.

The R4M rockets, typically mounted in wooden racks beneath the wings with 24 on each side, carried powerful Hexogen-filled warheads. Early firing problems were traced to fragile copper electrical connectors, a flaw quickly resolved by reinforcing them with silver or nickel.

Each MK-108 cannon could fire more than 650 rounds per minute. Engineers appreciated the weapon for its compact shape, low manufacturing cost, and extraordinary striking force. A small burst could break apart a heavy bomber while keeping the jet far beyond the most dangerous zone of defensive fire.

The challenges, however, were real and persistent. The Jumo 004 engines, rushed into production under intense wartime pressure, suffered from delicate components and a lack of high-quality alloys. Debris from exploding aircraft could be sucked into the compressor, causing immediate flameouts. A crippled Me-262 on one engine was suddenly vulnerable—unable to outrun a pursuing P-51 Mustang, P-47 Thunderbolt, or Mosquito. Galland often lamented the engine’s fragility; with better alloys and more stable production, he believed they would have lasted far longer than the meager 12-hour service life many achieved late in the war. By 1945, shortages of nickel and chromium made the situation even worse, with some engines failing before they even left the test stands.

Starting the powerplant was another peculiarity. Because the compressor had to spin up before ignition, the engineers used a small two-stroke gasoline engine behind the nozzle—essentially a mechanical helper. Many postwar jets later relied on electric starters or auxiliary turbines, but the Me-262 needed either an electric push or, in some cases, a literal pull-cord similar to a lawnmower. The fighter had armored glass and a reinforced seat back, but no ejection seat. Pilots were expected to roll inverted and let gravity and airflow pull them clear in an emergency—often a terrifying prospect at the jet’s high speeds.

The Jet’s First Leap Into the Sky

The Me-262’s maiden flight occurred on March 25, 1942. Test pilot Fritz Wendel took the sleek prototype into the air and reached a speed of roughly 541 miles per hour, astonishingly fast for its time. The streamlined, shark-like silhouette of the jet made an immediate impression, but political interference slowed its path into combat. Adolf Hitler repeatedly demanded it be configured as a high-speed bomber rather than a pure fighter. Designer Willi Messerschmitt, Galland, and others nodded outwardly while quietly prioritizing the fighter concept. Their hope was that the Arado 232 and similar designs would eventually satisfy Hitler’s bomber ambitions.

Still, valuable time and resources were diverted to producing modified Me-262 bombers. Others were adapted into reconnaissance machines or night fighters. The diversion frustrated Galland deeply; he insisted that if fighter development had proceeded without interference, the jet could have entered service much earlier and perhaps forced the Allies to rethink their approach to daylight bombing.

Despite Hitler’s early resistance, the two-seat night fighter versions eventually proved themselves. With a radar operator seated behind the pilot, these variants tracked bombers through darkness and cloud cover. Oberleutnant Kurt Welter, already an experienced night fighter in FW-190s and Me-109s, became the most successful jet night fighter pilot, credited with around 20 confirmed kills—many of them Mosquitos, which were considered among the hardest planes in the world to intercept.

The Me-262 in Real Combat

Frontline units began receiving Me-262s in April 1944. The first recorded encounter occurred in July when one of the jets fired on a British Mosquito that trailed smoke but managed to land in Italy. By August, the Germans had scored their first confirmed jet victory. Meanwhile, Allied intelligence grew increasingly concerned. Resistance reports, reconnaissance photos, and OSS briefings all pointed to a new kind of threat. Many pilots still doubted the idea at first; a fighter that fast seemed almost unbelievable.

Doolittle recalled a bomber pilot who had been nearly overwhelmed by a sudden Me-262 attack. A single 30mm shell entered through the bomb bay, killing one crewman and injuring several others. Had the bomber still been carrying its payload, the explosion could have ignited the bombs and destroyed multiple aircraft in the formation. The shaken pilot never fully recovered his confidence. The Americans quickly understood that continuing morale depended on countering the jets decisively.

Finding Weakness in the German Jet

In response, reconnaissance intensified and airfields suspected of housing jets were repeatedly bombed. As the front shifted, the Germans were forced to operate from makeshift runways closer to the country’s center—even using sections of autobahn as temporary landing strips and hiding their jets in nearby forests to shield them from prowling Mustangs.

The Allies soon focused on the jet’s most vulnerable moments: takeoff and landing. P-51s patrolled these zones relentlessly, often scoring multiple kills when Me-262s were slow and exposed. The Germans countered by turning their airfields into deadly traps ringed with 88mm guns and supported by FW-190s and Me-109s ready to ambush attackers.

Galland later acknowledged that while bombing aircraft factories had limited effect, striking petroleum plants and railway networks was devastating. Without fuel, even the best pilots and machines could not compete. More critically, Germany lost irreplaceable airmen. “Planes can be rebuilt, but men cannot be made,” he admitted after the war.

The introduction of drop tanks and the forward deployment of P-51s from mainland Europe prolonged Allied fighter presence over Germany. Once freed from strict escort duties, Mustang pilots aggressively hunted anything that moved—especially jets attempting to climb into the fight.

American pilots also experimented with nitrous oxide injection systems similar to the German GM-1 boosters. These systems delivered a brief surge of power, helping propeller-driven fighters close the distance on a fleeing Me-262. Tight four-plane formations also proved surprisingly effective; when positioned correctly, they denied the jet the room it needed to escape. Colonel Irwin Dregne noted that under the right circumstances, such formations could destroy the jet “on every encounter.”

Operation Bodenplatte: Germany’s Desperate Counterstrike

As the Allies grew more effective at grinding down the jet force through attrition, the Germans attempted several bold maneuvers of their own. One of the most daring was Operation Bodenplatte, a massive New Year’s Day strike designed to cripple Allied airfields across the continent. Generalmajor Dietrich Pelz believed that if Germany could demolish enough Allied fighters on the ground—destroying runways, fuel stores, maintenance facilities, and aircraft at rest—the Me-262 units might finally gain the breathing room needed to challenge Allied air superiority.

The concept was ambitious but fundamentally weakened by Germany’s shrinking pool of operational aircraft. What did launch, however, still struck with surprising force. On January 1, 1945, German units swept over Allied installations and managed to destroy more than 285 aircraft, including about 145 fighters, while damaging many more and causing over 180 casualties among air personnel. For a single coordinated Luftwaffe operation so late in the war, the numbers were staggering. Yet even this dramatic blow could not alter the long-term trajectory. The Allies possessed the production capability to replace their losses rapidly, whereas Germany lacked both the fuel and the trained pilots necessary to sustain prolonged jet operations.

Assessing How Many Me-262s Reached the Fight

More than 1,400 Me-262s were built in total, an impressive number considering the ravaged state of German industry in the war’s final years. But these figures mask a harsher truth: only about 50 aircraft reached full combat approval according to Adolf Galland, and at no point were more than 25 jets operational simultaneously. What looked formidable on paper was often an illusion in practice. Engine failures, fuel shortages, pilot attrition, and the relentless bombing of manufacturing centers all crippled Germany’s ability to deploy its jet fleet.

Some historical records suggest that upward of 180 aircraft may have been available at one time or another—including night fighters, bombers, and reconnaissance variants—but documentation from the collapsing Nazi bureaucracy was notoriously inconsistent in early 1945. The same ambiguity surrounds the total number of aerial victories achieved by Me-262 pilots. Modern estimates hover above 500, though precise confirmation remains elusive.

Despite these operational challenges, the Me-262 represented a profound technological leap. No other nation fielded a jet fighter of comparable capability during the conflict. Had Germany possessed the metallurgy needed for durable engines, the fuel supplies required for consistent deployment, and the time to refine production, the jet might have exerted far greater influence in the war’s closing years. Its revolutionary design paved the way for the jet age, setting benchmarks that shaped postwar aviation across the globe.

The aircraft stands today not only as a symbol of engineering ambition under extraordinary pressure but also as a reminder of how innovation can emerge even in the darkest periods of history. The Me-262’s performance, its limitations, and its brief but intense combat record all helped define the transition from piston-driven aerial warfare to the new era of high-speed jet combat—a transformation that reshaped military aviation forever.