The idea of a third world war carries a unique kind of fear. It’s not just about armies clashing or borders shifting; it’s about a level of destruction that would ripple across every society, economy, and generation. Unlike past global wars, another one would unfold in a world that is tightly interconnected, technologically fragile, and armed with weapons capable of ending civilization as we know it. That reality makes the question feel both urgent and unsettling: could the world really stumble into something that large again?

What makes this question especially difficult is that modern conflict rarely announces itself clearly. There is no formal declaration, no single shot that everyone agrees marks the beginning. Instead, tensions simmer for years. Rivalries harden, alliances tighten, red lines are drawn and quietly crossed. Economic pressure, cyber operations, proxy wars, and political signaling all blur the line between peace and open conflict. By the time people agree that a war has begun, it may already be impossible to contain.

History offers an uncomfortable lesson here. The world has repeatedly convinced itself that large-scale war was unlikely or irrational, right up until it happened. Leaders believed crises could be managed, adversaries could be deterred, and escalation could always be controlled. Those assumptions did not survive contact with fear, miscalculation, and pride. Today’s global system is different in many ways, but human behavior has not changed as much as technology has.

This is not a question about villains or simple blame. A third world war would not begin because one country wakes up and chooses destruction for its own sake. It would emerge from pressure points where interests collide, where misunderstandings pile up, and where decision-makers feel boxed in by expectations at home and threats abroad. Each side would likely believe it was acting defensively, responding to danger rather than creating it.

To understand the risk, it’s necessary to look beyond headlines and ask harder questions. Where are the most dangerous flashpoints? How do alliances turn local conflicts into global ones? What role do nuclear weapons, cyber warfare, and economic shocks play in accelerating escalation? And most importantly, why do systems designed to prevent war sometimes fail at the worst possible moment?

Exploring who might start World War 3 is really about examining how the modern world handles power, fear, and uncertainty. The answer is less about identifying a single aggressor and more about recognizing the conditions under which catastrophe becomes possible — and how close the world allows itself to drift toward that edge.

Who Will Start "World War 3" ?

What “Starting a World War” Really Means

The idea of starting a world war implies intention, but history suggests escalation is usually accidental, gradual, or misunderstood. World War I began with a single assassination, but that act alone did not cause the war. What followed was a cascade of alliances activating, mobilizations triggering counter-mobilizations, and leaders believing they had no room left to back down.

World War II followed a different pattern, driven more clearly by expansionist ambitions, unresolved grievances from the previous war, and economic collapse. Even then, it unfolded over years through invasions, occupations, and appeasement before exploding into full global conflict.

A third world war, if it ever happens, would likely not start with a single dramatic moment. It would probably begin as a regional conflict that draws in allies, spreads across domains like cyber and space, disrupts global trade, and escalates faster than diplomacy can keep up.

The Role of Major Powers

When discussing global war, attention naturally turns to the world’s most powerful states. Not because they are uniquely aggressive, but because their actions carry global consequences.

The United States sits at the center of a vast network of military alliances and security commitments. Its role as a global power means that conflicts involving allies can quickly become larger confrontations. Military presence across multiple regions increases deterrence, but it also increases the number of flashpoints where misunderstandings or incidents could spiral.

China represents a different kind of risk. Its rapid rise, economic weight, and growing military capabilities have shifted the global balance of power. Disputes over Taiwan, maritime control, and regional influence are often cited as potential triggers. None of these automatically lead to global war, but they exist in an environment where pride, credibility, and strategic signaling matter as much as material strength.

Russia brings yet another dynamic. Its actions are often shaped by perceptions of encirclement, historical trauma, and the desire to reassert influence. Conflicts on its borders can quickly take on a larger meaning, especially when opposing alliances are involved.

None of these powers necessarily want a world war. In fact, all would suffer immensely from one. The danger lies in how each interprets the actions of the others under pressure.

Alliances and Automatic Escalation

One of the most dangerous aspects of modern geopolitics is not rivalry itself, but interconnected obligations. Defense treaties are meant to deter aggression by promising collective response. At the same time, they reduce flexibility in moments of crisis.

If a regional conflict breaks out involving a treaty-bound ally, major powers may feel compelled to intervene even if they would otherwise prefer restraint. Each intervention increases the risk of miscalculation, especially when multiple nuclear-armed states are involved.

History shows that once mobilization begins, political leaders often feel trapped by their own commitments. Backing down can be perceived as weakness, both domestically and internationally. In a hyper-connected media environment, that pressure is even stronger.

Nuclear Weapons and the Illusion of Stability

Nuclear weapons are often described as a stabilizing force, based on the idea that mutual destruction prevents major war. There is truth to this, but it comes with serious caveats. Deterrence depends on rational decision-making, accurate information, and reliable communication — conditions that cannot be guaranteed during crises.

False alarms, misread signals, or cyber interference could compress decision timelines to minutes. The more complex military systems become, the greater the chance that something goes wrong at exactly the wrong moment.

Paradoxically, the belief that nuclear war is unthinkable can also encourage risk-taking below that threshold. States may push boundaries, assuming escalation will stop before the worst happens. History suggests that such assumptions are often wrong.

Economic Pressure and Resource Competition

Global conflict is not driven by ideology alone. Economic stress has played a major role in past wars, and it remains a powerful force today. Supply chain disruptions, energy dependence, food insecurity, and financial sanctions all increase pressure on governments.

When economic survival feels threatened, leaders may turn outward to distract from internal problems or to secure critical resources. Trade wars, embargoes, and technological restrictions can harden rivalries and make compromise politically costly.

In a tightly interconnected global economy, economic shocks do not stay local. A crisis in one region can ripple outward, amplifying instability elsewhere.

Technology as an Accelerator

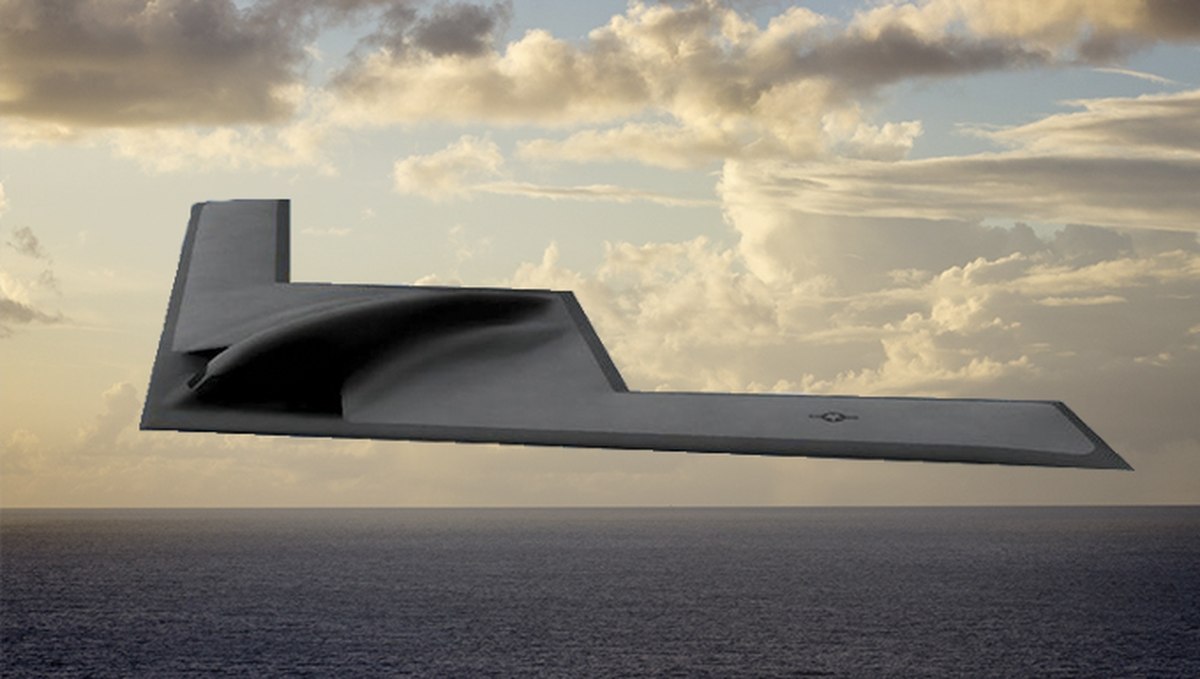

Modern warfare no longer depends solely on soldiers and tanks. Cyber operations, satellite systems, artificial intelligence, and information warfare blur the line between peace and conflict. Attacks can occur without clear attribution, making retaliation difficult to calibrate.

A cyberattack on critical infrastructure could be interpreted as an act of war even if no shots are fired. Disabling communications, financial systems, or power grids can have effects comparable to traditional military strikes.

The speed of modern technology also shortens reaction time. Decisions that once took days now take minutes, increasing the risk of irreversible escalation based on incomplete information.

So, Who Would Start It?

The uncomfortable answer is that no single country would “start” World War 3 in the way people imagine. It would emerge from a chain of events involving fear, miscalculation, rigid commitments, and rapidly unfolding crises. Each side would likely believe it was acting defensively, responding to provocation rather than initiating catastrophe.

World wars are not born from evil masterminds alone. They are born from systems that fail under pressure.

Flashpoints That Could Spiral

While no single nation is likely to wake up and decide to start a world war, certain regions carry a higher risk of escalation simply because of how many interests collide there at once. These flashpoints matter not because war is inevitable, but because mistakes in these areas are harder to contain.

East Asia is often mentioned first. Tensions around Taiwan combine military posturing, national identity, economic dependency, and alliance commitments. Any conflict there would immediately involve major powers and disrupt global trade routes that affect nearly every economy on Earth. Even a limited confrontation could expand rapidly if misjudged.

Eastern Europe remains another sensitive zone. Conflicts near major alliance borders test red lines and credibility. When military exercises, troop movements, or defensive deployments are interpreted as preparation for attack, the risk of escalation increases even if no side intends to go further.

The Middle East adds a different layer of complexity. Multiple overlapping rivalries, proxy conflicts, and external interventions create a volatile environment. Regional wars can easily pull in outside powers due to energy security, counterterrorism interests, or treaty obligations.

The South China Sea, the Korean Peninsula, and even space-based infrastructure have also emerged as areas where confrontation could escalate beyond initial expectations.

Miscalculation and the Human Factor

One of the least discussed but most dangerous elements in global conflict is human psychology. Leaders operate under pressure, with incomplete information, domestic political constraints, and personal beliefs shaping their decisions. History is full of moments where wars expanded not because leaders wanted them, but because they misread intentions or overestimated their own control over events.

Military doctrines often rely on deterrence through strength, but deterrence depends on both sides understanding each other clearly. When signals are ambiguous or deliberately provocative, the margin for error shrinks. A routine patrol, a missile test, or a cyber intrusion might be intended as a message, yet interpreted as preparation for attack.

Once forces are mobilized, the fear of being caught unprepared can push decision-makers toward escalation rather than restraint. This dynamic is especially dangerous in environments where communication channels are weak or mistrusted.

The Role of Smaller Conflicts and Proxy Wars

Another misconception is that world wars start directly between great powers. In reality, they often grow out of smaller wars that attract outside involvement. Proxy conflicts allow major powers to compete indirectly, but they also create pathways to direct confrontation.

When advisors, weapons, intelligence, and logistics flow into a regional conflict, the line between proxy and participant becomes blurred. If personnel are killed or critical assets are damaged, pressure builds for retaliation. Each step taken in response raises the stakes.

Modern proxy wars also unfold across multiple domains at once. Cyber operations, economic sanctions, and information campaigns accompany physical fighting, making escalation harder to track and even harder to stop.

Media, Public Opinion, and Speed

In earlier eras, governments could manage public narratives with relative control. Today, information spreads instantly and often without context. Images, videos, and claims — true or false — can inflame public opinion within hours. Leaders may find themselves reacting not just to events on the ground, but to viral outrage and political pressure at home.

This speed creates incentives to act quickly rather than carefully. Delays can be framed as weakness, while aggressive responses are sometimes rewarded politically. In a crisis, this dynamic can push states toward confrontation even when quieter diplomacy might still be possible.

At the same time, misinformation and disinformation complicate decision-making. False reports of attacks or exaggerated claims of enemy intent can spread faster than official clarifications, increasing confusion at critical moments.

Could World War 3 Be Prevented?

Despite all these risks, global war is not inevitable. In fact, the same systems that make escalation dangerous also provide tools for restraint. Diplomatic channels, international institutions, back-channel communication, and crisis hotlines exist precisely to prevent misunderstandings from becoming disasters.

Economic interdependence, while a source of tension, also raises the cost of war to levels that are difficult to justify. Global supply chains mean that even a regional conflict can trigger worldwide economic pain, creating strong incentives for de-escalation.

Public awareness also plays a role. Societies that understand the true cost of large-scale war are more likely to pressure leaders toward restraint. While fear can drive conflict, it can also motivate caution when the consequences are clear.

The More Honest Question to Ask

Instead of asking who will start World War 3, a more useful question might be how close the world allows itself to get to the edge. Large-scale wars are rarely the result of a single decision. They grow out of habits, assumptions, and unresolved tensions that accumulate over time.

World War 3, if it ever occurs, would almost certainly be described afterward as a tragedy no one intended but many contributed to. The warning signs are not secret. They are visible in rising distrust, rigid alliances, unchecked escalation, and the belief that catastrophe can always be avoided at the last moment.

History suggests that belief is the most dangerous one of all.