The Vietnam War was one of the longest, most expensive, and most deeply polarizing conflicts of the twentieth century. It brought the communist leadership of North Vietnam into direct confrontation with South Vietnam and its strongest backer, the United States. What began as a regional struggle over independence and political identity gradually escalated into a major Cold War battleground, shaped by global fears of communism, colonial legacies, and competing visions for Vietnam’s future.

Over the course of the war, more than three million people lost their lives, the majority of them Vietnamese civilians. Entire regions were devastated, families were displaced, and the psychological toll reached far beyond the battlefield. In the United States, the war fractured public opinion and eroded trust in political leadership, effects that lingered long after American forces withdrew in 1973. When communist forces finally took control of South Vietnam in 1975, Vietnam was reunified under a single government, but the scars of the conflict remained deeply embedded in both nations.

Roots of the Vietnam War

Vietnam sits along the eastern edge of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, a region that for decades had been shaped by foreign control and resistance movements. Beginning in the nineteenth century, Vietnam was ruled by France as part of French Indochina. Colonial authorities controlled land, resources, and political power, while much of the Vietnamese population lived under economic hardship and limited autonomy.

During the Second World War, the situation grew even more complex. Japanese forces occupied Vietnam, weakening French authority but not fully replacing it. In response to both Japanese occupation and lingering French influence, nationalist and revolutionary movements gained momentum. Among them was Ho Chi Minh, a political leader influenced by communist ideology and inspired by revolutions in China and the Soviet Union. He helped organize the Viet Minh, formally known as the League for the Independence of Vietnam, with the goal of ending foreign domination and creating an independent nation.

When Japan was defeated in 1945, its troops withdrew from Vietnam, leaving behind a sudden power vacuum. Emperor Bao Dai, who had been educated under French influence, briefly assumed authority. Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh moved quickly, seizing Hanoi and declaring the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, with Ho as its president. For many Vietnamese, this moment symbolized long-awaited independence, but for France, it represented a direct challenge to its colonial claims.

Determined to reassert control, France supported Bao Dai and established the State of Vietnam in 1949, with Saigon as its capital. At this point, the struggle was no longer simply about independence. Both sides sought a unified Vietnam, but their visions differed sharply. Ho Chi Minh and his supporters wanted a socialist state modeled on other communist systems, while Bao Dai and his allies favored closer economic and cultural ties with Western nations.

When the Conflict Turned Into War

Although American involvement would later define the Vietnam War, armed conflict in the region had been unfolding for years before U.S. troops arrived. By the early 1950s, fighting between communist forces in the north and French-backed forces in the south had intensified. The decisive turning point came in May 1954, when Viet Minh troops defeated French forces at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. This loss effectively ended nearly a century of French colonial rule in Indochina.

Soon after, representatives met at an international conference in Geneva to determine Vietnam’s future. The resulting agreement temporarily divided the country along the 17th parallel. The north came under the control of Ho Chi Minh’s government, while the south remained under non-communist leadership. Nationwide elections were scheduled for 1956 to reunify the country, but those elections would never take place.

In 1955, Ngo Dinh Diem, a fiercely anti-communist politician, removed Emperor Bao Dai and declared himself president of the Republic of Vietnam, commonly known as South Vietnam. With strong backing from the United States, Diem positioned his government as a bulwark against communism in Southeast Asia. This move deepened the division between north and south and set the stage for a much broader conflict.

The Rise of the Viet Cong

As Cold War tensions intensified around the globe, the United States grew increasingly committed to containing communism wherever it appeared to be spreading. President Dwight D. Eisenhower pledged firm support to Diem’s government, seeing South Vietnam as a critical line of defense in the region.

With assistance from U.S. military advisers and intelligence agencies, Diem launched an aggressive campaign against suspected communist sympathizers in the south. Many of these individuals were labeled Viet Cong, a term Diem used dismissively to describe Vietnamese communists. Tens of thousands were arrested, and reports of torture and executions became widespread. These crackdowns bred resentment and fueled resistance rather than eliminating it.

By the late 1950s, opposition groups began organizing armed attacks against government officials and military targets. In 1960, various anti-Diem factions, both communist and non-communist, united under the banner of the National Liberation Front. Although the NLF claimed independence from Hanoi, U.S. officials largely believed it was directed by North Vietnam, reinforcing fears that the conflict was part of a broader communist strategy.

Domino Theory and Growing U.S. Involvement

When John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency, his administration reassessed conditions in South Vietnam. Reports warned that Diem’s government was struggling to contain the insurgency. Advisers recommended expanding American military, economic, and technical assistance to prevent South Vietnam from collapsing.

This strategy was driven by the domino theory, the belief that if one country in Southeast Asia fell to communism, neighboring nations would soon follow. Kennedy increased aid and sent more military advisers, though he remained cautious about deploying large numbers of combat troops. Even so, by 1962, the American military presence in South Vietnam had grown to several thousand personnel, signaling deeper involvement.

The Gulf of Tonkin and Open War

Political instability in South Vietnam worsened after Diem was overthrown and killed by his own generals in 1963. His death, followed closely by Kennedy’s assassination, left both nations in uncertain hands. President Lyndon B. Johnson and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara responded by escalating American support for South Vietnam.

In August 1964, reports emerged that North Vietnamese patrol boats had attacked U.S. naval vessels in the Gulf of Tonkin. Johnson ordered retaliatory air strikes, and Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting the president broad authority to use military force without a formal declaration of war. This marked the beginning of sustained U.S. combat operations in Vietnam.

American bombing campaigns soon expanded beyond Vietnam’s borders. From 1964 to 1973, the United States conducted covert bombing operations in neighboring Laos, aiming to disrupt supply routes along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. These missions made Laos the most heavily bombed country per capita in history, despite its official neutrality.

By March 1965, Johnson committed U.S. combat troops to Vietnam. Within months, tens of thousands of soldiers were deployed, with numbers rising rapidly despite growing doubts among some advisers and increasing opposition at home. Allied nations such as South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand also sent forces, though on a much smaller scale.

Command and Strategy on the Ground

The ground war in South Vietnam was largely directed by General William Westmoreland, who coordinated closely with South Vietnamese leadership in Saigon. His strategy focused on attrition, measuring success by enemy casualties rather than territorial control. Large regions were designated as free-fire zones, where civilians were expected to evacuate and heavy bombardment was used to deny the enemy safe haven.

This approach displaced millions of civilians and devastated vast stretches of countryside. Despite mounting enemy body counts, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces continued fighting, replenished by supplies and troops moving along the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos and Cambodia. Support from China and the Soviet Union further strengthened North Vietnam’s military capabilities.

Growing Opposition and the War at Home

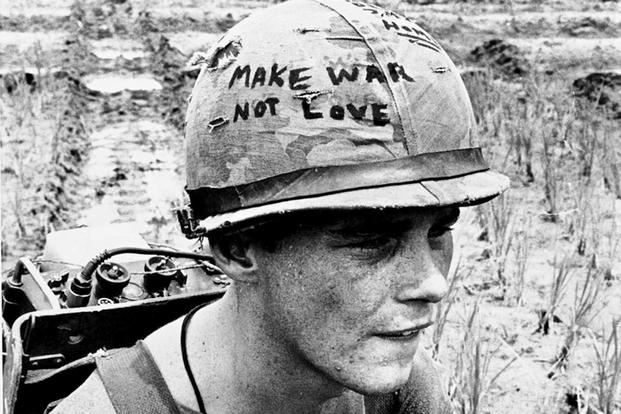

By the closing months of 1967, the Vietnam War had reached a scale that few Americans had imagined possible just a few years earlier. Nearly half a million U.S. troops were stationed in Vietnam, and casualty figures climbed relentlessly, appearing night after night in newspapers and television broadcasts. For many soldiers on the ground, optimism had faded. Official reports from Washington and military briefings often spoke of progress, enemy losses, and impending success, but these claims increasingly clashed with what troops were experiencing firsthand in the jungles, villages, and cities of South Vietnam.

As deployments grew longer and the enemy showed no sign of collapse, morale within the ranks deteriorated. Soldiers began openly questioning why they were fighting, what victory actually meant, and whether the sacrifices being demanded of them were justified. Psychological strain became widespread. Exposure to constant danger, guerrilla warfare tactics, and the blurred line between civilians and combatants contributed to rising cases of combat fatigue and trauma. Drug use increased as some soldiers sought escape from fear, boredom, and despair, while discipline problems and tensions between enlisted men and officers became more common.

At home, the war was no longer a distant conflict. For the first time in American history, a war was brought directly into living rooms through nightly television coverage. Graphic footage of firefights, wounded soldiers, and devastated Vietnamese villages deeply unsettled the public. These images undermined official reassurances and fueled a growing belief that the war was both unwinnable and morally compromised.

Public opposition surged. Protests spread from college campuses to major cities, drawing students, civil rights activists, religious leaders, veterans, and ordinary citizens into a broad anti-war movement. One of the most dramatic moments came in October 1967, when tens of thousands of demonstrators gathered outside the Pentagon, symbolizing a direct challenge to military and political authority. Critics argued that the war was causing immense civilian suffering, that South Vietnam’s government lacked legitimacy, and that the United States was entangled in a conflict it neither fully understood nor controlled.

The Tet Offensive

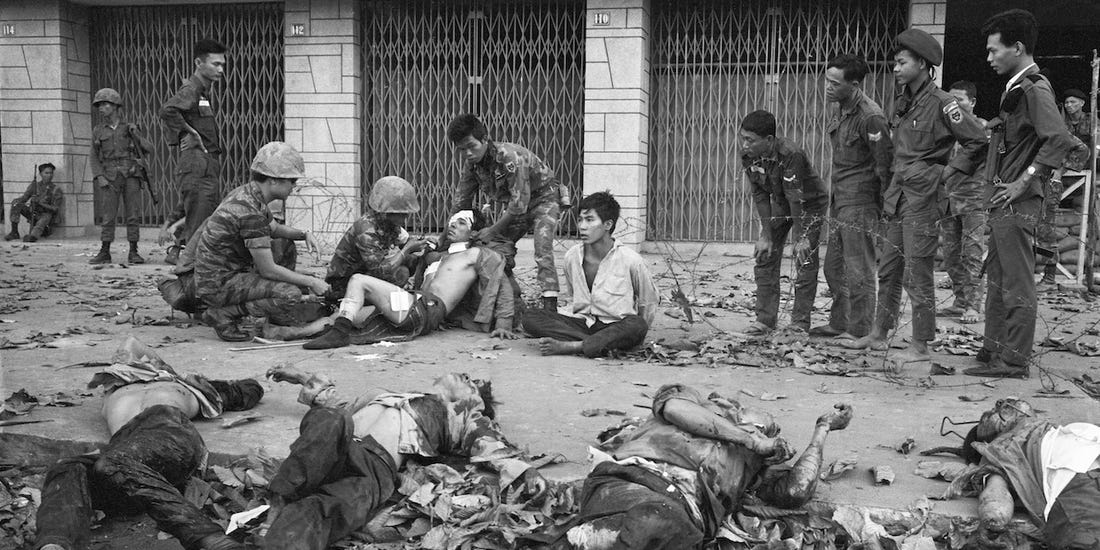

In early 1968, North Vietnam launched what would become the most consequential military action of the entire war: the Tet Offensive. Timed to coincide with Tet, the Vietnamese lunar new year traditionally associated with ceasefires and family reunions, the offensive caught U.S. and South Vietnamese forces by surprise. In a meticulously coordinated campaign, tens of thousands of North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong fighters struck simultaneously across South Vietnam, targeting more than one hundred cities, towns, and military installations.

The attacks reached places previously considered secure, including the U.S. Embassy compound in Saigon. Although American and South Vietnamese forces eventually repelled the assaults and inflicted heavy losses on the attackers, the psychological impact of the offensive was enormous. Militarily, the offensive failed to achieve its immediate objectives, but politically and psychologically, it was a turning point.

For the American public, Tet shattered the narrative that victory was near. The sheer scale and coordination of the attacks contradicted repeated assurances from military leaders that the enemy was weakening. Confidence in official statements eroded rapidly, and trust in government leadership declined even further.

The political consequences were swift. Facing growing opposition at home and mounting doubts within his own administration, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced a partial halt to bombing in North Vietnam and declared that he would not seek reelection. Peace talks began in Paris, signaling a shift toward negotiation rather than escalation. However, deep disagreements over conditions, representation, and the future of South Vietnam meant that progress remained slow and uncertain.

Vietnamization and Internal Crisis

When Richard Nixon assumed the presidency, he inherited a deeply unpopular war and a divided nation. Promising to restore unity and reduce American casualties, Nixon introduced a strategy known as Vietnamization. The core idea was to gradually withdraw U.S. ground troops while expanding and strengthening South Vietnamese forces so they could assume primary responsibility for combat operations.

Under this policy, American soldiers began returning home in increasing numbers, but the overall intensity of the war did not immediately diminish. U.S. air power and artillery strikes were expanded, and bombing campaigns intensified not only in Vietnam but also in neighboring regions linked to enemy supply routes. Nixon hoped this combination of withdrawal and military pressure would force North Vietnam to negotiate from a position of weakness.

Despite these efforts, peace talks continued to stall. North Vietnam demanded a complete and unconditional U.S. withdrawal and the removal of South Vietnam’s leadership, conditions Washington and Saigon were unwilling to accept. At the same time, revelations about atrocities committed by U.S. forces, most notably the massacre of civilians at My Lai, shocked the public. These disclosures further eroded support for the war and intensified moral opposition, reinforcing the perception that the conflict had gone profoundly wrong.

Protests, Expansion, and Tragedy

As the war expanded beyond Vietnam’s borders into Cambodia and Laos, domestic unrest in the United States flared once again. Many Americans viewed these incursions as reckless escalations that contradicted promises of de-escalation. College campuses became epicenters of protest, with demonstrations growing larger and more confrontational.

The most tragic symbol of this unrest occurred in May 1970 at Kent State University in Ohio. During a protest against the Cambodian campaign, National Guard troops opened fire on unarmed students, killing four and wounding several others. The incident sent shockwaves across the country, crystallizing fears that the war was tearing American society apart. Similar violence soon followed at other protests, further deepening divisions and hardening attitudes on all sides.

Meanwhile, the conflict itself dragged on. Negotiations continued intermittently, punctuated by renewed bombing campaigns and military operations designed to gain leverage at the bargaining table. These late-war air offensives drew sharp international criticism but ultimately contributed to renewed momentum in talks. Even so, the prolonged struggle left lasting scars, reinforcing the sense that the Vietnam War had reshaped not only Southeast Asia but also the political, social, and psychological landscape of the United States.

The End of the War and Its Aftermath

In January 1973, the United States and North Vietnam signed a peace agreement, ending direct American involvement. Fighting between North and South Vietnam continued until 1975, when northern forces captured Saigon and reunified the country.

The human and economic cost of the war was immense. Vietnam faced years of reconstruction, while the United States grappled with inflation, political distrust, and the long-term suffering of returning veterans. Memorials and public reflection gradually reshaped how the conflict was remembered, but its legacy continues to influence discussions of foreign policy, military intervention, and national identity.