The Cold War was a prolonged global struggle that emerged after the defeat of Nazi Germany, reshaping international politics for decades. Although the United States and the Soviet Union had fought as allies during World War II, their partnership was never rooted in shared values or long-term trust. It was a temporary alliance driven by necessity, forged to defeat a common enemy. Once that enemy was gone, deep ideological, political, and economic differences resurfaced with force.

The United States promoted a system built around representative democracy, private enterprise, and open markets. The Soviet Union, by contrast, advanced a centrally planned economic model combined with one-party rule and state control over political life. Each side viewed the other not merely as a competitor but as a direct threat to its way of life. As a result, cooperation quickly gave way to suspicion, rivalry, and strategic maneuvering.

In the postwar environment, much of Europe lay in ruins. Cities were destroyed, economies collapsed, and political systems were fragile. Both superpowers moved swiftly to shape the reconstruction of this shattered continent in ways that favored their own interests. The United States emphasized economic recovery, political stability, and democratic governance, believing that prosperity would prevent radical movements from taking root. The Soviet Union, having suffered immense losses during the war, focused on security above all else, seeking to ensure that no hostile power could again approach its borders.

This clash of priorities gradually hardened into a global confrontation. The world was increasingly divided into two rival camps, each aligned with one of the superpowers. While the Cold War did not involve direct, sustained combat between American and Soviet armies, it influenced nearly every major international crisis of the second half of the twentieth century. Conflicts, alliances, revolutions, and even scientific achievements were shaped by this enduring rivalry.

A Conflict Without Open War

From the late 1940s onward, the Cold War developed into a unique form of confrontation. Unlike traditional wars, it was defined less by direct battles and more by indirect pressure. The United States and the Soviet Union relied on political influence, military alliances, economic leverage, propaganda, and covert operations to weaken each other’s position without triggering a full-scale war.

Espionage became a central feature of this struggle. Intelligence agencies expanded rapidly, gathering information, conducting sabotage, and attempting to influence governments around the world. Media, culture, and education also became battlegrounds, as each side sought to present its system as superior. Films, radio broadcasts, newspapers, and even sports competitions were infused with ideological significance.

The most dangerous dimension of the Cold War was the nuclear arms race. Both superpowers developed vast stockpiles of nuclear weapons capable of destroying entire cities within minutes. This unprecedented destructive power introduced a grim paradox. While nuclear weapons made total war unthinkable, they also created a constant state of tension. The concept of deterrence emerged, based on the belief that neither side would launch an attack if it knew retaliation would be inevitable and catastrophic.

This balance, often described as a balance of terror, prevented direct confrontation but encouraged relentless military buildup. Each new weapon developed by one side prompted a response from the other. Periods of extreme tension were occasionally followed by moments of relative calm, known as détente, when dialogue increased and limited agreements were reached. Still, mistrust remained a defining feature of the relationship.

From Allies to Rivals in Europe

During World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union cooperated closely against Nazi Germany. Yet even before the war ended, cracks in the alliance were visible. Disagreements emerged over how Europe should be governed once the fighting stopped. These tensions became more pronounced during postwar conferences, where Allied leaders negotiated the occupation of Germany and the future of liberated territories.

The Soviet Union, devastated by invasion and enormous loss of life, was determined to prevent future attacks. To achieve this, it established a belt of friendly governments along its western frontier. One by one, communist-aligned regimes took power in Eastern European countries such as Poland, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia. Although these states retained their own governments, they followed policies closely aligned with Moscow.

In Western Europe, the United States pursued a very different strategy. American leaders believed that economic hardship and political instability could make societies vulnerable to extremist movements. To counter this risk, Washington committed unprecedented resources to European recovery. Financial aid flowed through large-scale reconstruction programs designed to stabilize economies, rebuild infrastructure, and strengthen democratic institutions.

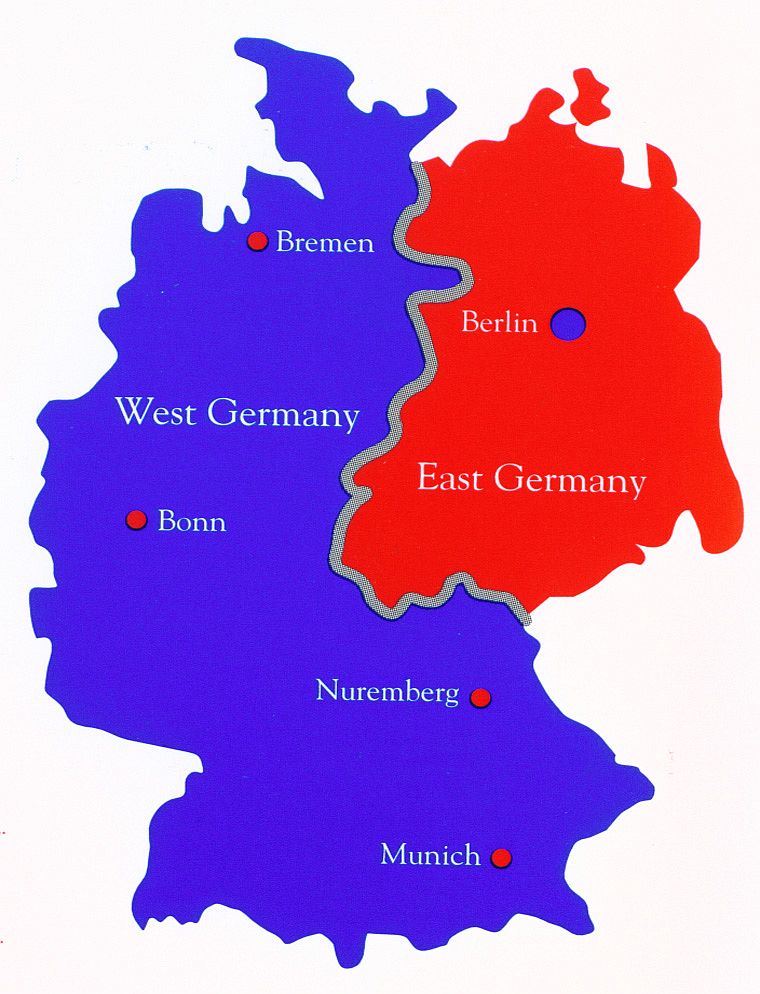

Germany became the central symbol of Europe’s division. Split into occupation zones, it embodied the competing visions of the two superpowers. Berlin, located deep within the Soviet-controlled zone, was itself divided. When Soviet authorities attempted to isolate West Berlin by cutting off land routes, Western powers responded with an extensive airlift that sustained the city for months. The crisis underscored how easily Cold War tensions could escalate.

The creation of formal military alliances cemented Europe’s division. Western nations formed a collective defense organization that bound the United States to the security of Europe. In response, the Soviet Union organized its own alliance system among Eastern European states. From that point forward, Europe remained largely stable but deeply divided, with heavily armed blocs facing each other across a fortified boundary.

The Cold War Goes Global

Although Europe was the initial focal point of the Cold War, the rivalry soon spread far beyond the continent. As colonial empires collapsed, newly independent nations emerged across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. These societies often faced internal divisions, economic challenges, and political instability, making them vulnerable to outside influence.

Both superpowers competed to shape the direction of these emerging states. Support came in many forms, including military assistance, economic aid, and political backing. Local conflicts were frequently drawn into the larger Cold War framework, transforming regional struggles into proxy wars.

In Asia, the victory of communist forces in China dramatically altered the global balance of power. The establishment of a communist government in the world’s most populous nation intensified American fears of ideological expansion. Soon after, war erupted on the Korean Peninsula, where rival governments claimed authority over the entire country. International intervention turned the conflict into a major Cold War confrontation, ending in a stalemate that reinforced global divisions.

Southeast Asia became another key arena. The collapse of European colonial rule created power vacuums that competing forces sought to fill. In Vietnam, the struggle for independence evolved into a prolonged conflict shaped by Cold War rivalries. Elsewhere, political movements in Africa and Latin America navigated a complex landscape of foreign pressure and domestic aspirations.

Even in the Western Hemisphere, Cold War tensions reached new heights. Revolutionary change in Cuba brought a government aligned with the Soviet Union to power just miles from the United States. This development intensified fears in Washington and underscored the truly global reach of the Cold War.

Leadership, Elections, and Cold War Rhetoric

By the end of the 1950s, the Cold War had become a defining feature of political life in the United States. Presidential elections increasingly revolved around questions of strength, resolve, and credibility on the global stage. Candidates competed to appear tougher than their opponents, promising to defend national security and counter Soviet influence wherever it appeared. Public anxiety over nuclear weapons, espionage, and ideological rivalry shaped debates far beyond foreign policy circles.

The election that brought John F. Kennedy to the presidency reflected this atmosphere. Both major candidates emphasized military preparedness and warned of the dangers posed by international communism. Kennedy, in particular, argued that the United States needed to modernize its armed forces and close what he described as a growing gap in nuclear capability. He also criticized earlier administrations for allowing revolutionary movements aligned with the Soviet Union to gain power close to American borders.

Kennedy’s presidency unfolded under intense Cold War pressure. As the first American leader born in the twentieth century, he framed the struggle as a generational test, one that demanded sacrifice, vigilance, and moral commitment. His speeches often portrayed the global conflict as a contest between freedom and authoritarian control, reinforcing the idea that American actions abroad were inseparable from the defense of democratic values at home.

The Bay of Pigs and Early Setbacks

One of the earliest crises of Kennedy’s administration stemmed from plans inherited from the previous government. American intelligence agencies had developed a scheme to support Cuban exiles in an armed attempt to overthrow the revolutionary government that had come to power in Havana. The expectation was that a landing by these exiles would spark a popular uprising and weaken the Cuban leadership.

Kennedy approved the operation, hoping it could be carried out discreetly and without direct American involvement. In practice, the plan unraveled almost immediately. When the invasion force landed on Cuba’s southern coast, it encountered stronger resistance than anticipated. Popular support failed to materialize, and the operation collapsed within days. Most of the invading force was captured or killed.

The failure was a serious blow to American prestige. It emboldened the Cuban government, strengthened its ties with the Soviet Union, and raised questions about U.S. judgment and effectiveness. Kennedy publicly accepted responsibility for the disaster, but privately the episode deepened his awareness of the risks inherent in Cold War decision-making.

Escalation of the Nuclear Arms Race

Cold War tensions intensified further during meetings between Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. At their summit in Vienna, discussions quickly revealed deep mutual suspicion. Khrushchev adopted a confrontational tone, pressing Western leaders on issues such as Germany and access to Berlin. Kennedy left the meeting convinced that the Soviet leadership was prepared to test American resolve.

Shortly afterward, the Soviet Union moved to seal the border between East and West Berlin by constructing a physical barrier. The wall became an enduring symbol of Cold War division, cutting through neighborhoods and families while visually representing the ideological split of Europe. Although it reduced the flow of refugees from East to West, it also hardened attitudes on both sides.

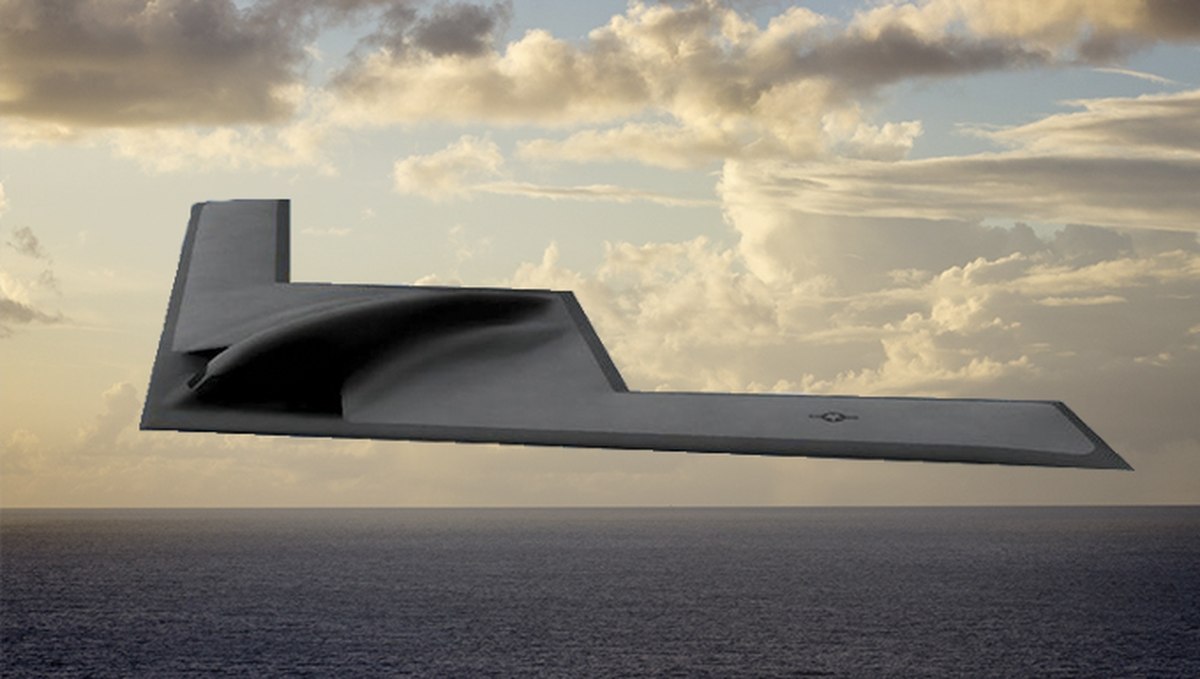

In response to these developments, the United States expanded its military capabilities. Nuclear missiles, conventional forces, and reserve units were increased in number and readiness. The Soviet Union answered with its own buildup. Both sides resumed nuclear testing, each seeking technological advantages that could shift the balance of power. The arms race accelerated, driven by fear, mistrust, and the belief that weakness could invite aggression.

The Cuban Missile Crisis

The most dangerous confrontation of the Cold War occurred when the Soviet Union secretly placed nuclear missiles in Cuba. The move was intended to protect the island from future attacks and to alter the strategic balance by positioning weapons close to American territory. When U.S. reconnaissance aircraft detected the missile sites, the discovery triggered an immediate crisis.

Kennedy and his advisers faced an agonizing set of choices. Direct military action risked provoking nuclear war, while inaction could undermine American credibility. The administration opted for a naval blockade, described as a quarantine, to prevent additional missiles from reaching Cuba. Tense negotiations followed, with both sides acutely aware of the catastrophic consequences of miscalculation.

After days of uncertainty, an agreement was reached. The Soviet Union agreed to dismantle the missile sites in exchange for assurances regarding Cuba’s security. Although the immediate danger passed, the crisis left a lasting impact. It exposed how close the world had come to nuclear war and underscored the need for improved communication and restraint.

In the aftermath, both governments took steps to reduce the risk of accidental conflict. A direct communication link was established between Washington and Moscow, and limited agreements were reached to restrict certain nuclear tests. These measures did not end the rivalry, but they reflected a shared recognition of the stakes involved.

Vietnam and the Limits of Cold War Power

While nuclear confrontation dominated headlines, the Cold War also unfolded through prolonged regional conflicts. In Southeast Asia, American involvement in Vietnam expanded gradually, driven by fears that the fall of one country to communism would destabilize the region. Military advisers were deployed in increasing numbers, and aid flowed to support local forces resisting communist movements.

Despite this growing commitment, American leaders remained uncertain about the extent of their responsibility. Public statements emphasized assistance rather than control, yet the line between advisory support and direct involvement became increasingly blurred. Decisions made under the pressure of Cold War rivalry carried long-term consequences, drawing the United States deeper into a conflict shaped by local history as well as global ideology.

Vietnam illustrated the limits of superpower influence. Superior military technology did not guarantee political success, and efforts to contain communism often collided with nationalist movements and internal divisions. The war became a powerful example of how Cold War assumptions could lead to prolonged and costly entanglements.

The Closing Phase of the Cold War

By the later decades of the Cold War, the rigid structures that had defined the rivalry began to weaken. Economic challenges, social pressures, and political reform movements reshaped the Soviet Union and its allied states. In Eastern Europe, demands for greater freedom and autonomy grew stronger, eroding the authority of long-standing communist governments.

The dismantling of physical and political barriers symbolized these changes. The collapse of the Berlin Wall marked a dramatic turning point, signaling the end of the division that had defined Europe for a generation. As communist regimes fell across Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union itself dissolved, the Cold War gradually came to an end.

The conflict left a complex legacy. It reshaped international institutions, transformed military strategy, and influenced countless lives across the globe. Although it never erupted into direct war between the two superpowers, its effects were felt in nearly every region of the world, leaving behind lessons about power, ideology, and the consequences of prolonged global rivalry.