Long before airplanes became reliable machines that could cross oceans and continents, flight was a dangerous idea filled with uncertainty, broken bones, and crushed dreams. Early flying machines were not born from neat equations or proven aerodynamic rules. They emerged from imagination, trial and error, and a deep human desire to escape gravity. Many of the earliest attempts at flight failed spectacularly, and some ended tragically, yet each failure pushed humanity closer to understanding how flight truly worked.

The story of early aviation is not a smooth path of progress. It is a long chain of experiments that often went wrong. Inventors copied birds without understanding lift, trusted engines that were too weak, and climbed into machines that had never been tested with a human aboard. What we now recognize as basic principles of flight were painfully unknown at the time. Before success came, aviation had to survive centuries of mistakes.

Dreams of Flight in Myths and Legends

Long before machines existed, humans imagined flight through myth. These stories reveal how deeply the idea of flying captured the human mind.

Ancient Greek legends described Pegasus, the winged horse that carried heroes across the sky, and the tragic tale of Icarus and Daedalus. Daedalus engineered wings made of wax and feathers, and while his own flight succeeded, his son Icarus flew too high. The sun melted the wax, and Icarus fell into the sea. The story reads like a warning about overconfidence, a lesson that would repeat itself many times in real aviation history.

Other legends echoed similar ideas. Persian mythology spoke of King Kaj Kaoos flying with the help of eagles attached to his throne. Alexander the Great was said to have ascended into the sky using griffins harnessed to a basket. These stories were not science, but they planted the idea that flight might one day be possible through clever design.

Early Attempts to Imitate Birds

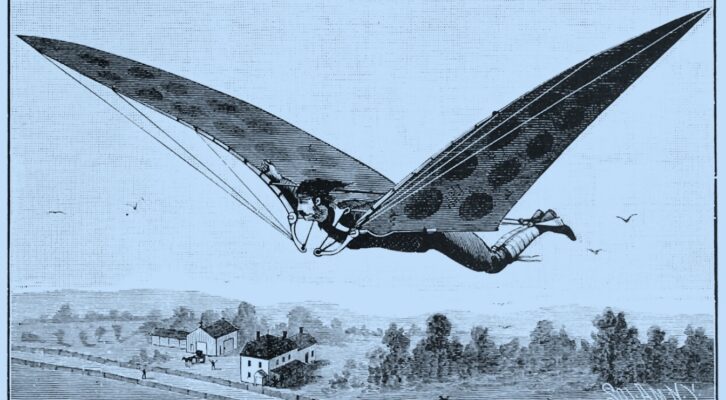

For centuries, humans believed the secret to flight lay in copying birds directly. Early inventors strapped feathered wings to their arms, leapt from towers, and attempted to flap their way into the air. These attempts almost always failed.

The problem was simple but not understood at the time: human muscles are not built for flight. Birds possess powerful chest muscles, lightweight bones, and highly specialized wing shapes. Human arms could not generate enough lift or thrust. Many early flyers were injured or killed when their machines failed to stay airborne, proving that imitation alone was not enough.

These disasters slowly taught inventors that flight required more than wings. It required an understanding of airflow, lift, balance, and control.

Kites and the First Lessons of Lift

One of the most important breakthroughs came from an unexpected source: kites. Around 400 BC, the Chinese developed kites not only for entertainment but also for military signaling and weather observation. Kites showed that objects heavier than air could be supported by wind when shaped correctly.

Though simple, kites introduced the concept of controlled lift. They demonstrated that wings did not need to flap to fly. This insight laid the foundation for gliders, balloons, and eventually airplanes. Without kites, the science of flight might have been delayed by centuries.

Hero of Alexandria and the Power of Thrust

In ancient Greece, Hero of Alexandria experimented with air pressure and steam. One of his most famous inventions was the aeolipile, a spherical device that rotated when jets of steam escaped from its sides.

While the aeolipile was not a flying machine, it introduced the idea of thrust produced by expelled gas. This concept would eventually become central to propulsion, from propellers to jet engines. Hero’s work showed that motion could be generated mechanically, even if true flight was still far away.

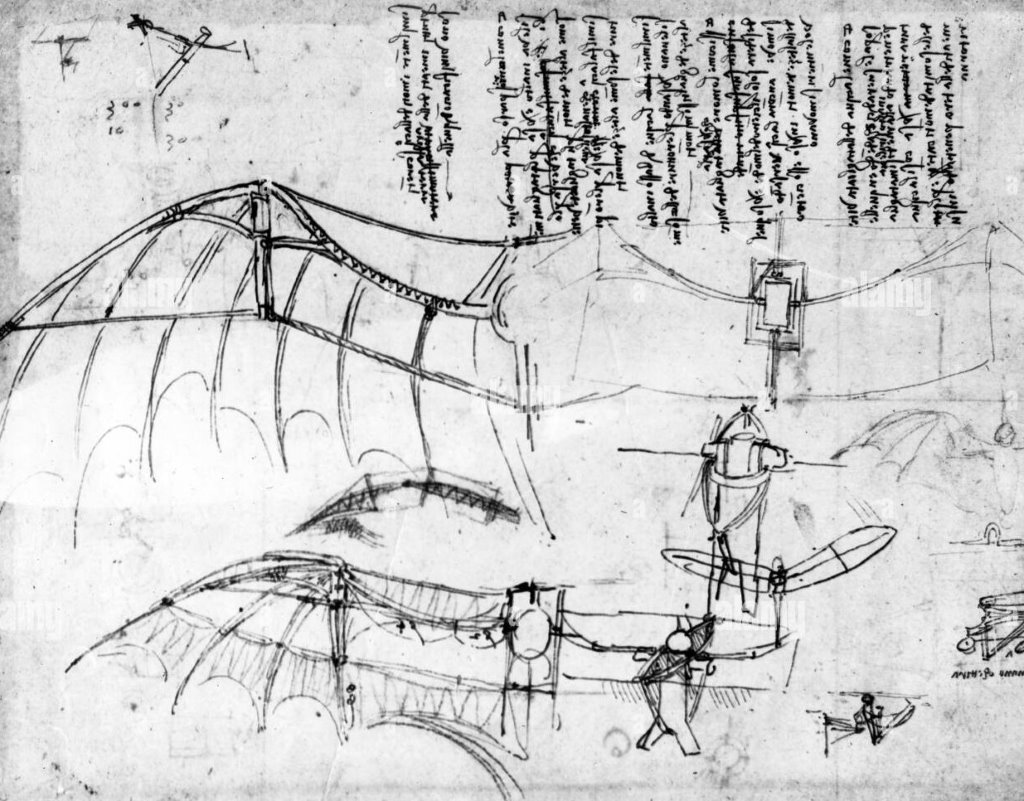

Leonardo da Vinci and the Ornithopter Problem

In the late 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci made the first serious scientific study of flight. He filled notebooks with detailed sketches of wings, airflow, and flying machines. His most famous concept, the ornithopter, relied on human-powered flapping wings.

Leonardo correctly understood many aspects of aerodynamics, but he still believed flapping flight was the solution. The ornithopter was never built during his lifetime, and modern reconstructions show that it would not have flown. The human body simply could not provide enough power.

Despite this failure, Leonardo’s work was revolutionary. He treated flight as a mechanical problem rather than a magical one, paving the way for future inventors.

Balloons and the First True Success

In 1783, the Montgolfier brothers achieved what many earlier inventors could not: sustained human flight. Their hot air balloon rose using heated air trapped in a fabric envelope. The first passengers were animals, followed soon after by humans.

Balloons proved that flight was possible, but they introduced new problems. Balloons could rise and fall, but they could not be steered effectively. They drifted wherever the wind carried them. While balloons marked a breakthrough, they were not the answer to controlled, powered flight.

George Cayley and the Birth of the Airplane Concept

George Cayley made one of the most important contributions to aviation by separating the forces of flight. He understood that lift, thrust, weight, and drag were distinct and had to be managed independently.

Cayley designed gliders with fixed wings, tails for stability, and separate control surfaces. Some of his gliders successfully carried human passengers, though not always safely. Crashes were common, but each failure refined the design.

Cayley also recognized that engines would eventually be necessary for sustained flight. His work defined the basic shape of the modern airplane long before engines were powerful enough to make it practical.

Otto Lilienthal and Fatal Progress

Otto Lilienthal was one of the first people to fly gliders repeatedly and systematically. He made over 2,500 flights, carefully recording his observations. His designs were based on careful studies of bird wings and airflow.

Lilienthal’s success came at a cost. In 1896, a sudden gust of wind caused him to lose control, and he crashed fatally. His death highlighted the dangers of early aviation, but his data became invaluable. The Wright brothers would later rely heavily on Lilienthal’s research.

Samuel Langley and the Weight Problem

Samuel Langley believed powered flight required engines, and he was right. His small steam-powered models flew successfully, proving that propulsion could sustain flight.

However, when Langley attempted to scale up his design for a manned aircraft, the machine became too heavy and structurally weak. It crashed into the water during launch attempts. Public failure and humiliation caused Langley to abandon his efforts.

His work demonstrated that engines alone were not enough. Balance, control, and structure mattered just as much.

The Wright Brothers and Controlled Flight

Orville and Wilbur Wright approached flight differently. Instead of rushing to build a powered airplane, they focused on control. They studied previous failures, built kites, tested gliders, and used wind tunnels to gather accurate data.

Their early gliders were unstable and difficult to manage, but each crash taught them something new. Wing warping gave pilots control in the air, solving one of aviation’s biggest problems.

When they finally added an engine, the result was the Wright Flyer. The first flight in 1903 was brief and unstable, but it worked. Over the next two years, the brothers refined the design until it became the first practical airplane.

Failure as the Foundation of Flight

The first flying machines failed far more often than they succeeded. Wings collapsed, engines stalled, pilots crashed, and theories proved wrong. Yet every mishap contributed to understanding how flight truly worked.

Modern aviation stands on the lessons learned from these early disasters. Without centuries of failed attempts, risky experiments, and tragic losses, controlled flight would never have become possible. The story of early aviation is not just about invention. It is about persistence, humility, and learning from failure — the true engines that lifted humanity into the sky.