Antimatter has long occupied a strange space between hard science and science fiction. It is real, measurable, and studied daily in laboratories, yet its potential power is so extreme that it often feels abstract or mythical. The idea of an antimatter bomb pushes this tension to the limit. It raises a simple but unsettling question: if antimatter is the most energy-dense substance known, what would actually happen if it were detonated on Earth?

To answer that, we first need to understand what antimatter really is, how energy is released when it meets normal matter, and why the gap between theory and reality is far wider than most people realize.

Understanding Antimatter Beyond Science Fiction

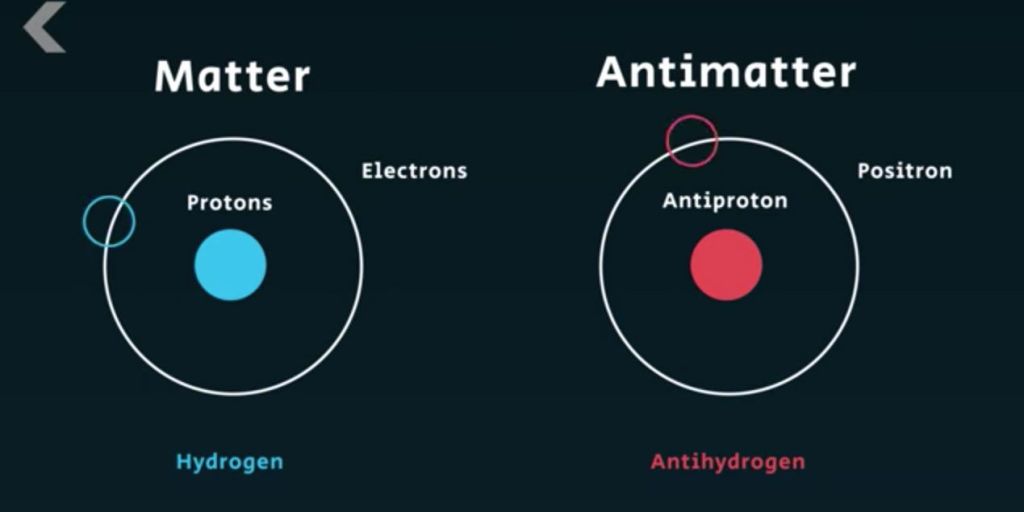

Antimatter is not a mysterious alternative form of matter with exotic behavior. At a fundamental level, it mirrors ordinary matter almost perfectly, with one critical difference: the electrical charge of its particles is reversed. Electrons have negatively charged counterparts called positrons, and protons have negatively charged equivalents known as antiprotons. When these particles encounter their matter counterparts, both are destroyed in a process known as annihilation, converting their mass directly into energy.

This phenomenon was predicted in the early twentieth century as physicists explored the implications of combining quantum mechanics with relativity. Experimental confirmation soon followed, and antimatter moved from theoretical curiosity to laboratory reality. Despite this, antimatter remains extraordinarily rare in the observable universe, a mystery that continues to challenge cosmology and particle physics.

In controlled environments such as particle accelerators, tiny amounts of antimatter are routinely created and studied. These quantities are measured in individual particles or, at most, a few atoms at a time. Even so, they allow scientists to test fundamental laws of physics with exceptional precision.

How Energy Is Released During Annihilation

When matter and antimatter meet, they do not explode in the conventional sense. Instead, they annihilate, converting nearly all of their combined mass into energy according to Einstein’s equation E = mc². This is what makes antimatter so potent. Chemical explosives release energy by rearranging atomic bonds, while nuclear weapons release energy by splitting or fusing atomic nuclei. Antimatter bypasses these steps entirely.

The energy released per unit mass is vastly greater than that of nuclear weapons. In principle, one gram of antimatter reacting with one gram of matter would release energy comparable to a large thermonuclear weapon. Unlike nuclear explosions, however, antimatter annihilation does not produce radioactive fallout in the same way, though it does generate intense radiation in the form of gamma rays and other high-energy particles.

This distinction matters when imagining real-world consequences.

What an Antimatter Bomb Would Actually Be

Despite popular imagery, an antimatter bomb would not resemble a traditional explosive filled with antimatter waiting to detonate. Antimatter cannot be stored in ordinary containers. The moment it touches normal matter, annihilation occurs. In laboratories, antimatter is held using complex electromagnetic traps that suspend particles in a vacuum using precisely tuned fields.

To create a weapon, one would need:

-

a method to store macroscopic amounts of antimatter,

-

a way to transport it safely,

-

and a mechanism to deliberately trigger annihilation at a chosen location.

At present, none of these requirements can be met at a meaningful scale. The total amount of antimatter ever produced by humanity is far less than what would be needed for even a tiny explosive yield.

Hypothetical Detonation: Immediate Effects

If we momentarily ignore feasibility and imagine a successful detonation, the immediate effects would depend entirely on the amount of antimatter involved.

At very small scales, such as micrograms, the explosion would resemble a powerful conventional blast, producing intense heat, light, and radiation over a limited area. At larger scales, the energy release would be catastrophic. Temperatures near the annihilation point would reach millions of degrees, vaporizing nearby materials instantly.

Unlike nuclear bombs, there would be no mushroom cloud driven by radioactive debris. Instead, the explosion would be dominated by a burst of high-energy radiation capable of causing severe damage to living tissue and electronic systems over a wide radius.

Atmospheric and Environmental Impact

An antimatter explosion would interact violently with Earth’s atmosphere. Air molecules near the blast would be ionized almost instantly, forming a rapidly expanding plasma. Shockwaves would propagate outward, flattening structures and causing widespread destruction depending on the yield.

On a larger scale, the environmental consequences would be severe but different from nuclear fallout. There would be no lingering radioactive contamination of soil or water. However, the radiation pulse could damage the ozone layer locally, increasing ultraviolet exposure in the affected region.

If such an explosion occurred near the surface, geological effects could include seismic disturbances and the creation of a crater, though again, these effects would scale with the amount of antimatter used.

Could an Antimatter Bomb Destroy the Planet?

Despite dramatic claims often found online, an antimatter bomb could not destroy Earth unless an absurdly large amount of antimatter were used. Planetary destruction would require energy comparable to the gravitational binding energy of Earth, far beyond anything conceivable with antimatter production.

Even the most extreme theoretical antimatter weapons discussed in scientific literature fall into the category of city-destroying or region-destroying events, not planet-destroying ones. Earth would survive, though the local devastation could be unparalleled.

Why Antimatter Weapons Remain Theoretical

The greatest barrier to antimatter weapons is not ethics or international law, but physics and economics. Creating antimatter is extraordinarily inefficient. Particle accelerators consume enormous amounts of energy to produce minuscule quantities of antimatter, most of which is lost during capture and storage.

Estimates place the cost of producing a single milligram of antimatter at tens of billions of dollars, and even that figure assumes idealized efficiencies. More importantly, it costs far more energy to create antimatter than could ever be recovered from its annihilation, making it an energy sink rather than a source.

Storage is equally prohibitive. Maintaining stable electromagnetic traps for extended periods without failure is already challenging at microscopic scales. Scaling this up introduces risks that current technology cannot manage.

Antimatter in Future Technology, Not Warfare

Where antimatter remains scientifically interesting is not in weapons, but in research and theoretical propulsion systems. Concepts involving antimatter-triggered fusion have been explored as possible future spacecraft propulsion methods, not because antimatter is practical, but because even tiny amounts can initiate reactions far more efficiently than conventional methods.

Even these applications remain speculative and distant. They highlight a recurring theme in antimatter research: its greatest value lies in understanding the universe, not in harnessing its destructive potential.

The Real Danger: Misunderstanding Antimatter

Perhaps the greatest danger posed by antimatter is not its hypothetical use as a weapon, but how easily its power is misunderstood. Popular culture often portrays antimatter as an instant apocalypse button, obscuring the reality that its production, storage, and control are among the hardest challenges in modern physics.

Antimatter reminds us that the universe contains energies far beyond everyday experience, but also that nature places strict limits on what can be exploited. The gap between what is theoretically possible and what is practically achievable remains vast.

A Thought Experiment With Clear Limits

Exploding an antimatter bomb on Earth is, for now, a thought experiment rather than a plausible scenario. It serves as a useful lens for discussing energy, physics, and the boundaries of technology, but it does not represent an imminent threat.

The real lesson of antimatter is not about destruction, but about humility. Even with our most advanced tools, the universe still resists being bent to human ambition.