World War I—often remembered as the “war to end all wars”—erupted in July 1914 and dragged on until November 11, 1918, leaving an astonishing trail of devastation behind it. More than 17 million people lost their lives, including well over 100,000 American soldiers who entered the conflict during its later stages. Although historians continue to debate the deeper forces that pushed nations toward this catastrophe, several widely recognized factors set the stage for a conflict unlike anything the world had seen. What follows is a detailed exploration of the most commonly cited developments that helped turn political tensions into a global inferno.

Mutual Defense Alliances

Countries across Europe—and even beyond—had built an intricate web of alliances long before the summer of 1914. These agreements pledged mutual defense: if one nation was attacked, its partners were obligated to step in. On the surface, such alliances could act as deterrents, discouraging aggression by raising the potential consequences. Yet in practice, they created a fragile, interconnected system where a single spark could activate multiple military commitments at once.

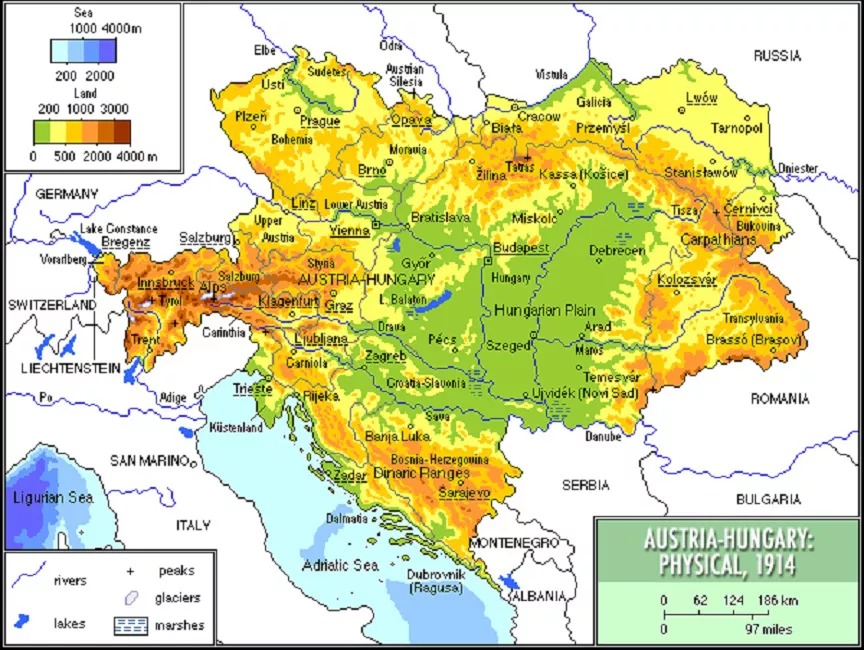

Several major alliances had formed by the early 20th century, reflecting rising insecurity and competition. Russia aligned itself with Serbia, a relationship built partly on shared Slavic identity and Russia’s desire for influence in the Balkans. Germany forged a powerful connection with Austria-Hungary, anchoring its presence at the center of Europe. France and Russia cooperated closely in response to their mutual anxiety about Germany’s growing strength. Britain, though historically cautious about alliances, formed strategic ties with both France and Belgium. Even Japan, far removed geographically, solidified its partnership with Britain.

This network meant that Austria-Hungary’s decision to declare war on Serbia did not remain an isolated confrontation. Russia’s intervention on Serbia’s behalf triggered Germany’s mobilization. France joined to support Russia, and Germany’s invasion route through Belgium pulled Britain into the fray. Japan followed shortly after, honoring its commitments. Later, Italy and the United States entered the war on the side that gradually came to be known as the Allies. A regional dispute had quickly transformed into a global crisis because nations were locked into promises that left little room for diplomatic escape.

Imperial Rivalries

Imperialism—the practice of expanding a nation’s influence by acquiring territory and controlling resources—was another driving force behind the rising hostility. Throughout the 19th century, Europe’s major powers raced to claim vast regions of Africa and Asia. These territories were valued not only for their natural resources but also for the prestige and strategic advantage they offered.

However, competing claims created constant friction. Germany, a relatively young empire compared to Britain or France, sought its “place in the sun,” pushing aggressively for overseas holdings. Britain, whose empire already spanned the globe, feared being challenged. France, still recovering from defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, was equally determined not to lose further ground. Smaller powers such as Italy also waded into imperial competition, hoping to elevate their global status.

These overlapping ambitions led to diplomatic crises and territorial disputes that heightened distrust among nations. The more each empire felt compelled to expand or defend its holdings, the more likely conflicts became. In the years leading up to World War I, resentment simmered beneath the surface of European politics, waiting for the right moment to erupt.

Militarism and the Arms Race

As the 20th century approached, European nations began pouring extraordinary resources into building bigger armies and more technologically advanced navies. Militarism—an ideology that promotes military strength as the key measure of national power—became deeply embedded in political culture. The belief that a strong military could both protect interests and intimidate rivals pushed governments to intensify spending and expand recruitment.

The fiercest competition unfolded between Britain and Germany. Britain had long dominated the seas, but Germany sought to challenge that supremacy by rapidly constructing modern warships. The launch of Britain’s revolutionary HMS Dreadnought in 1906 triggered an accelerated contest, compelling both nations to produce vessels with greater firepower, speed, and armor. Naval superiority became both a strategic necessity and a matter of national pride.

On land, the story was similar. Germany trained millions of young men and refined its mobilization system to move troops with unmatched efficiency. Russia expanded its forces, hoping to counter Germany’s might. France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and other nations followed suit. As military leaders gained more influence over national policy, discussions about diplomacy increasingly gave way to discussions about readiness for war.

By 1914, the continent was heavily armed, deeply suspicious, and primed for conflict. A single miscalculation could turn tension into violence—and eventually did.

Nationalistic Tensions Across Europe

Nationalism—a powerful emotional attachment to one’s cultural identity, homeland, or ethnic group—played a central role in destabilizing Europe. Nowhere was this more visible than in the Balkans, where diverse ethnic communities competed for independence, influence, and political unity.

Bosnia and Herzegovina had been absorbed into Austria-Hungary, but many Slavic inhabitants favored unification with nearby Serbia, where Slavic nationalism was rapidly growing. Serbia envisioned itself as the heart of a larger Slavic nation, creating intense anxiety within Austria-Hungary, which feared losing territory and weakening its already fragile empire.

These regional aspirations and resentments became catalysts for broader conflict. National pride influenced foreign policy across Europe, making countries more willing to take risks and less willing to compromise. Propaganda and patriotic rhetoric amplified the belief that war could be a legitimate or even glorious means of defending national honor. Once the war began, nationalism also sustained public support, convincing populations to endure hardships that might otherwise have sparked resistance.

The Trigger Event: Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Although the deeper causes of World War I had taken shape over decades, the immediate spark came on June 28, 1914, in Sarajevo. Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was visiting the region when a Serbian nationalist organization known as the Black Hand plotted an attack. Their goal was to strike a symbolic blow against Austro-Hungarian rule and promote the creation of a unified Slavic state.

The group’s initial attempt—a grenade thrown at the archduke’s car—failed. But later that day, Gavrilo Princip, a young member of the group, encountered Ferdinand’s vehicle by chance and fired the shots that killed both the archduke and his wife. The assassination shocked Europe and unleashed a chain reaction of diplomatic ultimatums, accusations, and mobilization orders.

Austria-Hungary responded by declaring war on Serbia. Russia prepared to defend Serbia, prompting Germany to declare war on Russia. France and Britain joined soon after, bound by alliances and growing alarm over German aggression. What might have remained a regional crisis escalated into a war involving multiple great powers within weeks.

The War to End All Wars

The outbreak of World War I marked a profound transformation in the nature of warfare. Advances in technology shifted combat away from traditional hand-to-hand fighting toward mechanized devastation: machine guns, tanks, chemical weapons, heavy artillery, and long-range rifles altered the battlefield forever. Trench warfare trapped millions of soldiers in brutal stalemates, turning once-quiet landscapes into scenes of unimaginable destruction.

By the time the armistice was declared in 1918, more than 15 million people were dead and over 20 million injured. The conflict reshaped borders, toppled empires, and sowed the seeds of future upheavals that would erupt again just two decades later. World War I did not end all wars, but it irrevocably changed how nations wage them—and how the world understands the cost of global conflict.