Building your own drone is no longer a niche hobby reserved for aerospace engineers or military contractors. With today’s components, open-source flight controllers, and widely available materials, it’s entirely possible for a motivated individual to design and assemble a capable, reliable drone tailored to specific needs. Whether the goal is aerial photography, mapping, inspection, research, or pure technical curiosity, a custom-built drone offers flexibility that off-the-shelf models simply cannot match.

Unlike buying a ready-made drone, building one forces you to understand how every system works together. You are not just assembling parts; you are designing an aircraft. That process leads to better performance tuning, easier repairs, and a much deeper understanding of flight dynamics.

This guide walks through the full process of building your own drone from the ground up, focusing on design decisions, component selection, engineering trade-offs, and real-world usability.

Understanding the Purpose Before You Build

Every successful drone build starts with a clear mission. Before selecting a single component, you need to define what the drone is meant to do.

Some drones are built for speed and range, others for stable hovering and precise control. A mapping drone may prioritize endurance and GPS accuracy, while an inspection drone may need compact size and excellent maneuverability. Trying to build a single drone that does everything often leads to compromises that hurt performance across the board.

Key questions to answer early include flight duration requirements, payload weight, operating environment, wind tolerance, launch and landing constraints, and whether autonomous features such as GPS hold or waypoint navigation are needed. These decisions influence every technical choice that follows.

Choosing the Right Drone Configuration

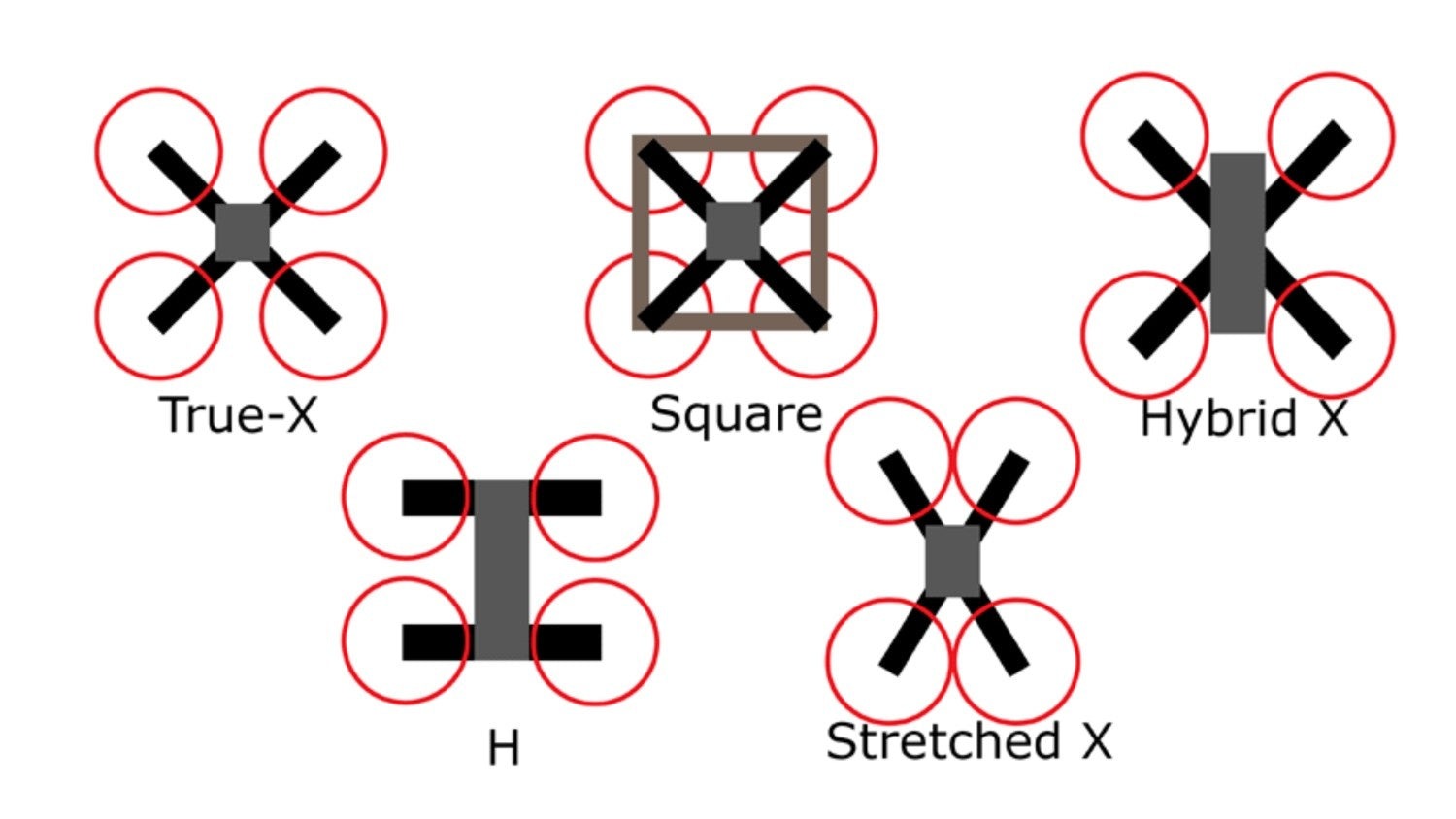

The airframe configuration defines how the drone flies and what it can do. The most common options are fixed-wing, single-rotor helicopter, and multi-rotor designs.

Fixed-wing drones excel at long-distance flight and efficiency but cannot hover. Helicopter-style drones can hover and carry heavy payloads but are mechanically complex and difficult to tune. Multi-rotor drones strike a balance, offering vertical takeoff, stable hovering, precise movement, and relatively simple construction.

For most custom builds, multi-rotor designs such as quadcopters, hexacopters, or Y-shaped configurations are the most practical. They can launch from confined spaces, remain stationary in the air, and move in any direction with fine control. This makes them ideal for photography, surveying, inspection, and experimentation.

The Importance of Flight Control Systems

A drone does not fly because of its motors alone. The true heart of the aircraft is the flight controller.

Multi-rotor drones are inherently unstable. Without constant adjustments, they would immediately tumble out of the air. The flight controller solves this problem by processing data from sensors and making rapid corrections hundreds or thousands of times per second.

Modern flight controllers rely on gyroscopes, accelerometers, magnetometers, and barometers to understand orientation, movement, and altitude. Advanced systems integrate GPS for position hold, return-to-home functions, and autonomous navigation.

Selecting a capable flight controller dramatically affects stability, safety, and ease of use. A good controller allows the drone to hover smoothly, resist wind, and respond predictably to pilot input. It also simplifies tuning, reducing the trial-and-error phase during initial flights.

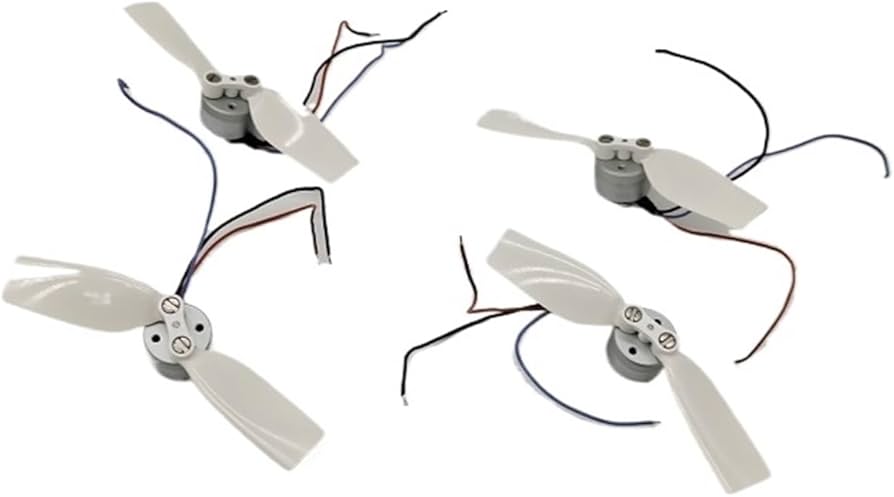

Motors, Propellers, and Thrust Balance

Motors and propellers generate the lift that keeps the drone airborne. Choosing the right combination requires balancing thrust, efficiency, weight, and responsiveness.

Each motor must be powerful enough to lift its share of the total weight while leaving headroom for rapid control adjustments. Underpowered systems struggle to stabilize, especially in wind or during aggressive maneuvers.

Propeller size and pitch affect how efficiently thrust is generated. Larger propellers tend to be more efficient but respond more slowly, while smaller propellers spin faster and provide quicker control. Matching motors and propellers correctly improves flight time, reduces vibration, and lowers stress on electronic components.

Redundancy can also be built into the design. Configurations with more motors than strictly necessary can remain controllable even if one motor fails, which is valuable for professional or experimental use.

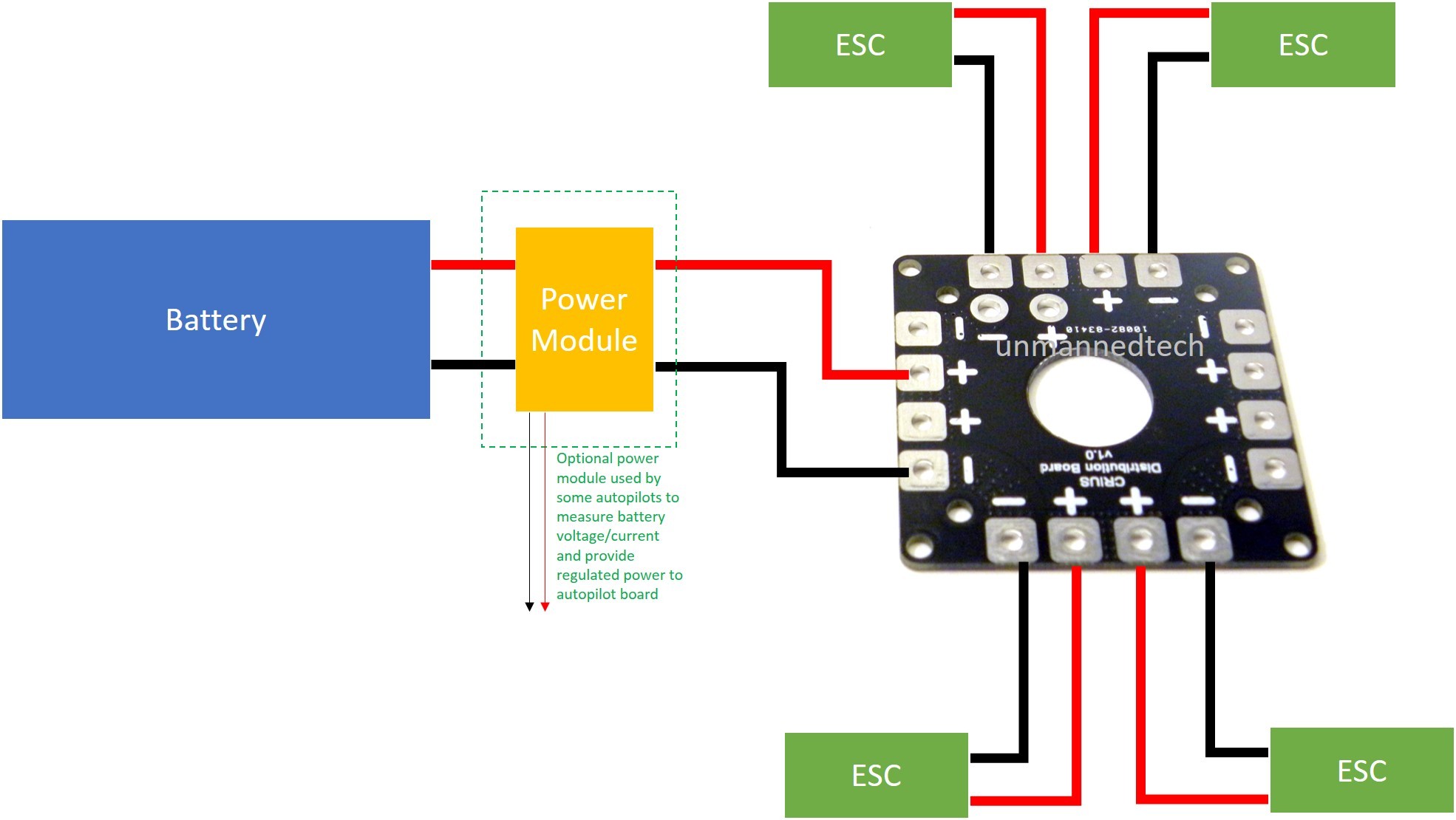

Power Systems and Battery Selection

The power system is one of the most critical aspects of a drone build. Batteries must deliver high current safely while remaining as light as possible.

Lithium polymer batteries are commonly used due to their high energy density and ability to provide large bursts of power. However, higher capacity batteries increase weight, which reduces agility and can cancel out gains in flight time.

Electronic speed controllers regulate power delivery to each motor. They must be matched to both motor current requirements and battery voltage. Poor-quality or mismatched controllers can cause overheating, power loss, or sudden shutdowns.

Proper wiring, soldering, and insulation are essential. A single loose connection can cause catastrophic failure in flight.

Remote Control and Communication Links

Reliable communication between the drone and the operator is essential for safety and usability. Control signals must remain stable even in environments with interference or obstacles.

Modern radio systems offer digital transmission, frequency hopping, and long-range capabilities. Some builds integrate telemetry links that send battery status, GPS position, altitude, and other data back to the operator in real time.

Failsafe settings are critical. If communication is lost, the drone should automatically reduce throttle, land safely, or return to its launch point using GPS. These features transform a custom drone from a risky experiment into a dependable aircraft.

Camera Systems and Payload Integration

Many custom drones are built to carry cameras or sensors. Payload integration must be considered early in the design process, not added as an afterthought.

Cameras introduce weight and require vibration isolation to prevent distorted footage. Gimbals or stabilized mounts allow the camera to remain level while the drone maneuvers, improving image quality and control.

Video transmission systems send live footage to the ground, enabling real-time navigation and monitoring. Antenna placement, shielding, and power management all affect signal quality and range.

A well-integrated payload feels like part of the aircraft, not a fragile attachment.

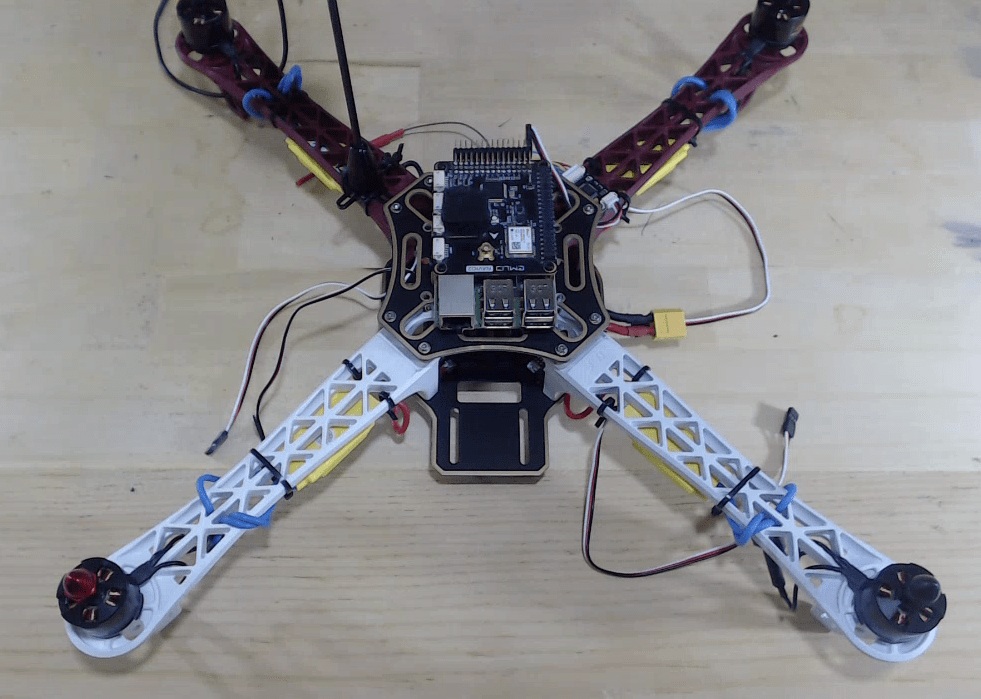

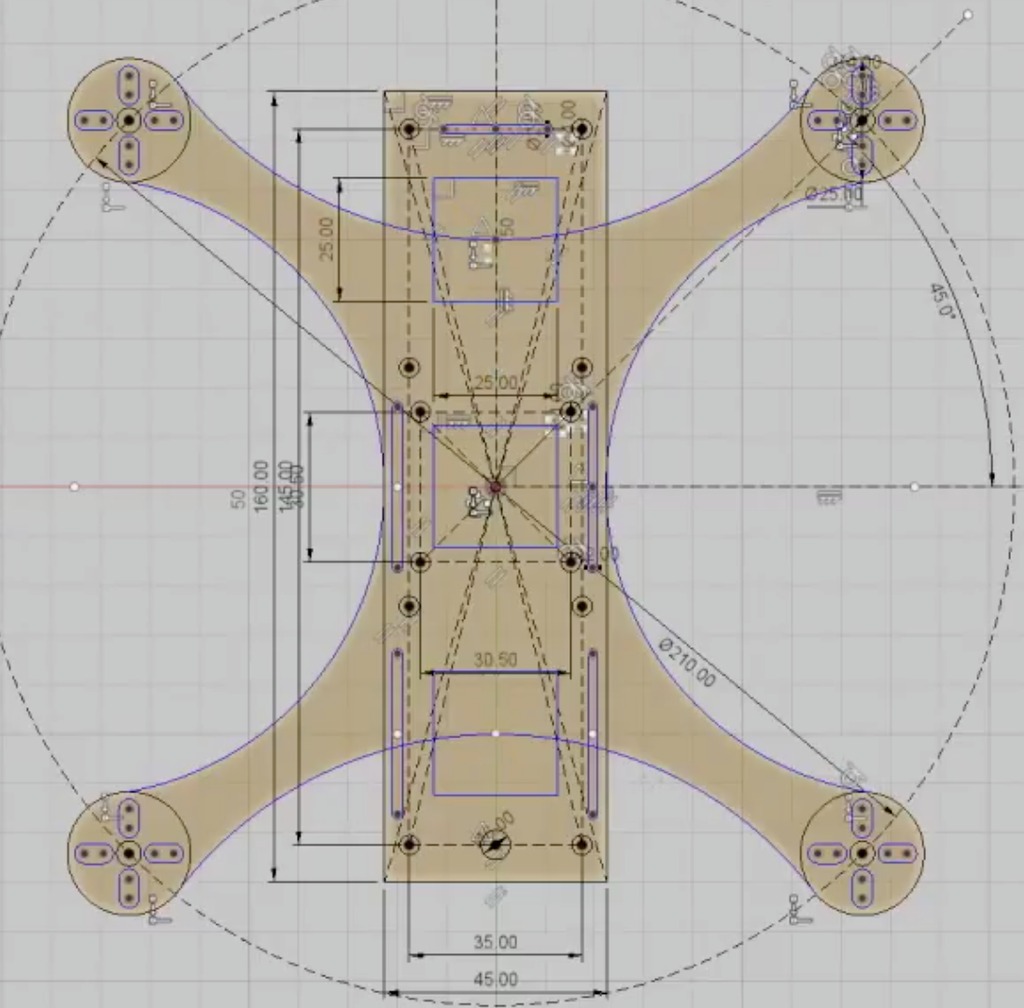

Designing and Building the Airframe

The airframe holds everything together and absorbs the stresses of flight. Materials such as carbon fiber, aluminum, and reinforced plastics are commonly used due to their strength-to-weight ratios.

A custom airframe allows components to be placed precisely for balance and protection. Internal wiring reduces exposure to damage, while modular design makes repairs easier.

Vibration damping is especially important. Excessive vibration can confuse sensors, degrade video quality, and shorten component lifespan. Careful layout, secure mounting, and material choice all contribute to smoother operation.

Even simple design tools can be used effectively if measurements are accurate and planning is thorough.

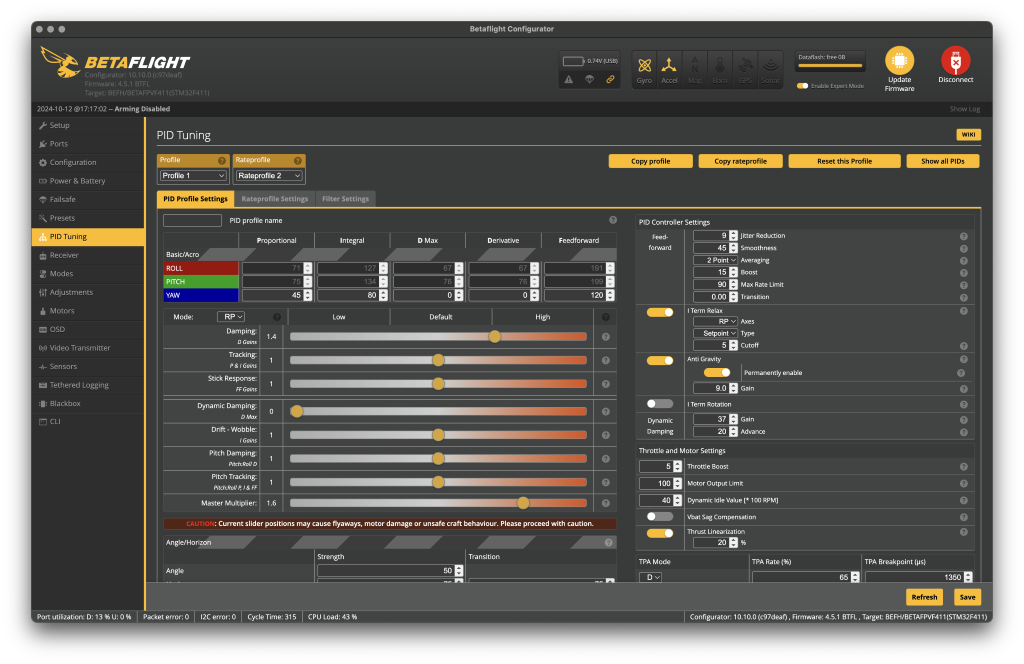

Assembly, Testing, and Tuning

Building the drone is only half the journey. Initial testing and tuning determine whether the aircraft performs safely and predictably.

Early flights should be short, low, and cautious. Motor direction, sensor orientation, and control responses must be verified before attempting complex maneuvers. Software tuning adjusts how aggressively the drone responds to inputs and how well it resists disturbances.

Crashes are not uncommon during this phase, but a well-designed drone can survive minor impacts with minimal damage. Each test flight provides data that improves reliability and performance.

Moving From Concept to Practical Use

Once properly tuned, a custom-built drone can rival or exceed commercial models in specific tasks. It can hover precisely, operate in challenging conditions, and carry payloads designed for exact needs.

Perhaps the most valuable outcome of building your own drone is not the aircraft itself, but the understanding gained along the way. Knowing how each system works together allows you to troubleshoot issues, adapt designs, and innovate beyond prepackaged solutions.

Building a drone is both an engineering challenge and a practical skill. With careful planning, patience, and attention to detail, it becomes entirely achievable—and deeply rewarding.