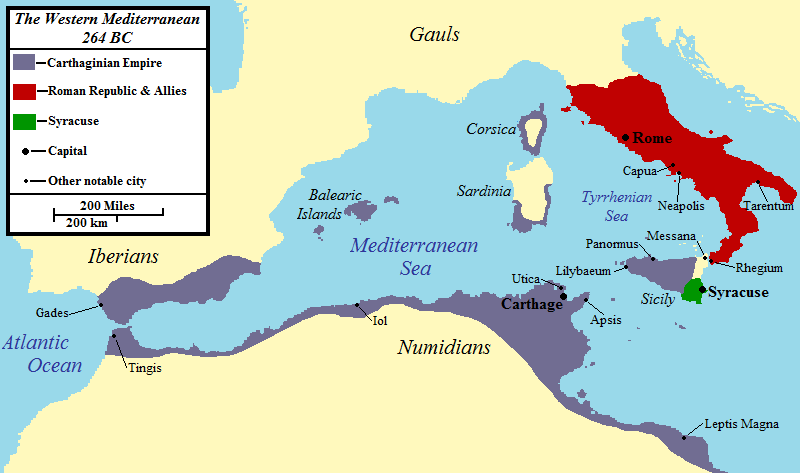

The long struggle known as the First Punic War marked the beginning of a historic clash between two rising Mediterranean powers—Rome and Carthage. This confrontation unfolded over more than two decades and permanently altered the balance of power across the ancient world. The broader series of conflicts between these empires came to be called the Punic Wars, a name rooted in the term “Punic,” which itself derived from the Latin Punicus, referring to the Phoenician ancestry of the Carthaginians. Although Carthage began as a modest coastal stopover, its strategic position and merchant networks allowed it to expand into one of the wealthiest and most influential cities on the Mediterranean coast.

By the early 3rd century BCE, Carthage commanded vast resources, operated a formidable navy, and relied on a diverse mercenary army supported by the profits of trade, tribute, and tariffs. An early treaty with Rome restricted Roman maritime activity in the western Mediterranean—a restriction Rome had little ability to resist, as it fielded no navy at all. When Roman traders crossed into Carthaginian waters, they paid with their vessels and often their lives. These tensions simmered beneath the surface long before open conflict erupted.

First Punic War (264–241 BC)

The events that directly sparked the First Punic War began in the 280s BCE, when a group of displaced Italian mercenaries known as the Mamertines—“Sons of Mars”—seized control of Messana, a key stronghold overlooking the narrow strait between Sicily and the Italian mainland. Whoever controlled Messana controlled movement and commerce across that vital waterway. In 265, when Hiero II of Syracuse moved to expel the Mamertines, they appealed to a nearby Carthaginian fleet for protection. The Carthaginians intervened swiftly, forcing Hiero to withdraw. Yet the Mamertines soon found the presence of their new Carthaginian allies suffocating and looked instead to Rome, claiming kinship with their fellow Italians. Despite Rome’s deep distrust of the Mamertines—having only recently executed another band of rogue mercenaries for similar behavior—the Senate recognized that allowing Carthage to entrench itself in Messana would place hostile forces dangerously close to Italian soil. Greed for plunder and fear of Carthaginian expansion overpowered Roman reluctance. A Roman force under Consul Appius Claudius Caudex crossed into Sicily to intervene.

Upon hearing that Roman troops were approaching, the Mamertines convinced the Carthaginian commander to pull his soldiers out of Messana. This withdrawal, however, filled the commander with regret, and he soon aligned himself with Hiero of Syracuse. United, the Carthaginian and Syracusan armies encircled Messana and initiated a siege. Negotiations collapsed in frustration, and the conflict escalated. Both Rome and Carthage entered the war confident that victory would come swiftly. Neither side could foresee the sheer scale of devastation and endurance this conflict would demand—a war stretching across generations, reshaping the political landscape of the western Mediterranean, and setting the stage for Hannibal’s future campaign.

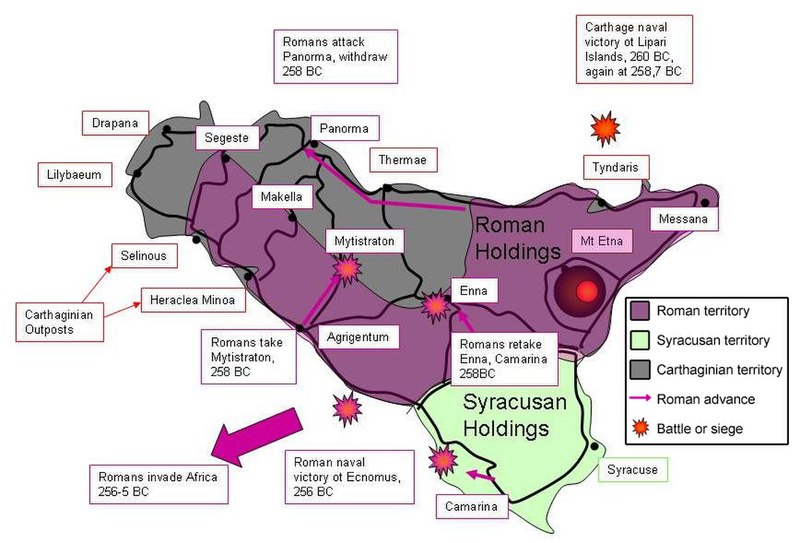

Because Sicily stood at the heart of the struggle, it became the primary battleground. Rome rapidly advanced into the island, seizing Messana and then forcing Syracuse to submit. Carthage, furious at the strategic blunder that had allowed Rome to land forces on the island, executed the offending general and reverted to its tested defensive method: a strategy built around fortified cities and mobile harassment. Their experienced mercenaries would pressure Roman allies and wait for openings to reclaim lost ground. This cautious approach had long served Carthage well in its conflicts with Greek city-states. However, they soon discovered that Rome was a fundamentally different foe—bigger, more relentless, and prepared to endure staggering losses.

The Western Mediterranean in 264 BC: Rome is shown in red, Carthage in purple, and Syracuse in green

In 262 BCE, Rome turned its attention to the fortified city of Agrigentum. After defeating a Carthaginian relief force, the Romans stormed the city and plundered it mercilessly. This victory did not merely weaken Carthage’s foothold in Sicily; it signaled Rome’s intention to expel Carthaginian influence from the island entirely. Instead of discouraging Carthage, the destruction of Agrigentum hardened its resolve. Subsequent Roman attempts to capture additional Carthaginian-held cities proved slow, costly, and in many cases ineffective. The island descended into a grinding stalemate in which cities changed hands repeatedly, shifting allegiance through negotiation, betrayal, or force.

Finally recognizing that Sicily could not be secured without matching Carthage at sea, Rome undertook a bold naval expansion program. They rapidly constructed a fleet and trained crews in an astonishingly short period of time. Early losses underscored their inexperience, but Roman ingenuity soon produced a solution: the corvus, a hinged boarding bridge fitted with an iron spike. This device allowed Roman marines to grapple onto enemy vessels, turning a naval confrontation into the kind of close-quarters combat Rome excelled at. In 256, armed with more than 300 ships and approximately 150,000 men, the Romans defeated a Carthaginian fleet near Cape Ecnomus—a victory that opened a path directly to Africa.

The Roman invasion of Africa in 256–255 began with remarkable momentum. Under Consul Atilius Regulus, Roman forces pillaged the countryside and forced Carthage to sue for peace. Yet when Rome presented terms far harsher than the Carthaginians could accept, the desperate city hired the Spartan commander Xanthippus to reorganize its defenses. With disciplined infantry, superior cavalry, and the devastating power of war elephants, Xanthippus led Carthage to a dramatic victory on open ground. Of the more than 15,000 Roman soldiers who fought in the battle, only about 2,000 survived to be rescued by the fleet. Regulus was captured, and Rome’s hopes of a swift conquest collapsed. Soon after, disaster struck again: nearly the entire evacuation fleet perished in a storm before reaching Italy, drowning tens of thousands of men and erasing Rome’s African ambitions. The war shifted once more back to Sicily.

As Roman forces struggled to rebuild, Carthage regained momentum in the western part of the island. Before long, however, Rome resumed its advance, capturing numerous Sicilian towns and tightening the noose around Carthaginian positions. Eager to force a decisive blow, Rome dispatched a fleet to raid the Libyan coast in 253, only to lose 150 ships and over 60,000 men to another catastrophic storm. Meanwhile, Carthage reinforced its Sicilian army with one hundred war elephants—a reminder of the crushing defeat inflicted on Regulus. Rome hesitated, taking years to reorganize and press the attack on Lilybaeum, the key fortress anchoring Carthage’s final strongholds.

At Lilybaeum, familiar frustrations resurfaced. Despite Rome’s siege, the Carthaginian fleet—commanded by the daring admiral Ad Herbal—continued to slip past Roman ships with ease, delivering supplies and reinforcements. One such maneuver so enraged the Roman consul Publius Claudius Pulcher that he planned a surprise assault on the Carthaginian fleet stationed at Drepana. His ships appeared at dawn outside the harbor with every advantage, but a fateful delay—caused by his insistence on awaiting a favorable omen—allowed Ad Herbal to escape the trap. The Roman fleet, boxed in against the coast and maneuvering poorly, suffered a crushing defeat with the loss of ninety ships. Only days later, another Roman fleet of 120 warships and hundreds of transports was obliterated in yet another storm. Rome would require seven years to muster the resolve and resources to build a new fleet capable of ending the war.

An photograph of the remains of the naval base of the city of Carthage. The remains of the merchantile harbour are in the centre and those of the military harbour are bottom right. Before the war, Carthage had the most powerful navy in the western Mediterranean.

Despite the staggering losses, Rome persisted. Both sides, exhausted and depleted, slipped into a grueling series of ambushes, raids, and brutal reprisals. Hamilcar Barca—father of the future general Hannibal—launched a daring guerilla campaign, striking Roman forces with mobility and cunning. By 243 BCE, however, Rome committed to a final push. A newly financed fleet destroyed one Carthaginian naval force by storm and another at the decisive Battle of the Aegates Islands in 241. In Carthage, a political faction advocating peace gained control, and the long war finally approached its end.

Rome emerged victorious, largely because Carthage had never devised a coherent strategy to defeat a larger, more relentless enemy. Roman losses were horrific, yet Rome consistently rebuilt its forces and adapted its tactics, while Carthage remained locked in a defensive mindset that squandered opportunities. Hamilcar’s brilliance proved insufficient to overcome strategic inertia. The lessons he absorbed during the war would shape Hannibal’s daring offensive in the years to come.

As part of the peace terms, Carthage surrendered Sicily and its surrounding islands, refrained from interfering with Rome’s allies, released Roman prisoners without ransom, and agreed to pay an enormous indemnity amounting to thousands of talents of silver. Rome, which had never fought beyond the Italian peninsula, now controlled its first overseas province. Yet victory came at staggering cost. Over 600 Roman ships were lost, along with an estimated 50,000 Roman citizens and hundreds of thousands of allied soldiers. Carthage, too, was left devastated—stripped of its naval supremacy, drained of resources, and nursing deep resentment.

Their long-standing relationship, once marked by trade agreements and uneasy cooperation, devolved into bitterness. Romans increasingly portrayed Carthaginians as treacherous and cruel, invoking the expression Punica fides—“Carthaginian faith”—to mean the worst kind of duplicity. Propaganda painted Carthaginians as corrupt, weak, and immoral, accusations that likely mirrored Carthaginian views of Rome. Although the peace held for over two decades, the seeds of a far greater conflict had already taken root.

Continued Roman advance 260–256 BC

Between the Wars

Carthage’s crushing defeat and the economic collapse that followed ignited a brutal uprising among its mercenaries and African allies—a conflict remembered as the Mercenary War or the “Truceless War” (241–237 BCE). Rome, though officially supporting Carthage, exploited the chaos to seize Sardinia and Corsica while demanding additional reparations. Eventually, under the leadership of Hamilcar Barca and his son-in-law Hasdrubal the Fair, Carthage subdued the rebellion. Hamilcar’s success dramatically increased his family’s influence and reputation, elevating them to a position of prominence within Carthaginian politics.

With major territories lost in Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica, Carthage looked to rebuild its fortunes elsewhere. Hamilcar set his sights on Hispania, a region rich in silver and other resources. By the early 3rd century BCE, Carthage had reestablished its wealth and strength there. Rome, satisfied with its recent gains, focused on governing its expanding territories and consolidating control in northern Italy. Between 225 and 222 BCE, Rome subdued the Gauls and soon turned eastward toward Illyria. Yet events unfolding in Hispania would soon shatter this stability and draw Rome once more into a conflict from which it could not easily retreat—a conflict that would ultimately bring Hannibal across the Alps and set the ancient world ablaze.