The figure of Achilles stands at the center of Greek mythology as one of its most celebrated warriors, a man whose name became synonymous with strength, courage, beauty, and tragic vulnerability. The legends surrounding him paint a portrait of a hero who seemed almost invincible, a warrior capable of shifting the balance of an entire war by simply stepping onto the battlefield. Yet, woven into his legacy is the reminder that even the greatest heroes carry a weakness—what we now call an “Achilles heel.” Much of what the world knows about him comes from Homer’s epic The Iliad, which recounts a turbulent and emotionally complex version of Achilles during the final stretch of the Trojan War, capturing both his glory and his flaws with striking depth.

Achilles: Early Life

Like many mythological heroes, Achilles’ beginnings were shaped by a mixture of divine influence and human fragility. His father, Peleus, ruled as the mortal king of the Myrmidons, a legendary people renowned for their unwavering bravery and disciplined skill in combat. They were considered almost superhuman in their loyalty and ferocity, which made the young prince’s lineage impressive even before considering his mother. Thetis, a Nereid and a goddess of the sea’s shimmering depths, added a divine thread to Achilles’ story and played an enormous role in shaping the details of his fate.

From the moment he was born, Thetis was haunted by the knowledge that her son was destined to live a life touched by danger. Later myths—written long after Homer’s time—describe a mother desperate to shield her child from mortality. Some stories say she attempted to burn away his human weakness by passing him through fire each night, soothing the burns with divine ointments. Others tell of her carrying him to the River Styx, a place believed to bestow supernatural invulnerability, and dipping him into its cold waters. But because she held him tightly by the heel, that small part remained untouched by the magic—leaving a single vulnerable point on an otherwise indestructible hero.

As Achilles grew, prophecies added new urgency to Thetis’ fears. A seer foretold that he would die young during a war against the Trojans, achieving everlasting fame at the cost of his life. Terrified by this vision, Thetis disguised her son as a girl and hid him among the daughters of the king of Skyros, hoping fate might lose sight of him. But the nature of Achilles could not be disguised forever. His fierce spirit, restlessness, and natural talent for battle pulled him away from hiding and toward the Greek forces assembling for war.

Even with his destiny looming, Thetis made one final plea to protect him. She asked Hephaestus, the masterful divine blacksmith, to forge armor worthy of a warrior who hovered between mortality and immortality. The resulting shield and weapons became legendary for their craftsmanship and symbolism. They were not enough to grant Achilles eternal life, but they served as unmistakable markers of his identity—instantly recognizable on the battlefield, inspiring awe in allies and dread in enemies.

When Homer composed The Iliad, however, audiences did not yet know these later myths. To them, Achilles was the embodiment of heroism: strong beyond measure, breathtakingly brave, and strikingly handsome. Homer complicated this image, revealing a young man capable of deep loyalty and love, but also impulsive, emotional, and prone to a furious pride that could turn the tide of war. His humanity—his contradictions—made him unforgettable.

The Trojan War

The legendary backdrop of Achilles’ greatest battles begins with a dispute that spiraled far beyond a simple rivalry. According to myth, Zeus sought a way to manage the swelling population of mortals on Earth. His solution was to spark a conflict between the Greeks and the Trojans, using the passions and rivalries of gods and humans as fuel. During the grand wedding feast of Achilles’ parents, the seeds of the coming war were planted when Paris, a prince of Troy, was chosen to judge a beauty contest between three goddesses—Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. Each offered a tempting bribe, but Aphrodite’s gift was irresistible: the most beautiful woman alive.

That woman was Helen, daughter of Zeus, who happened to be married to Menelaus, the king of Sparta. Yet Paris, guided by Aphrodite, journeyed to Sparta, won Helen’s affection, and brought her to Troy along with a treasure trove of riches. Menelaus’ fury ignited a coalition of Greek leaders who vowed to reclaim Helen and punish Troy for the insult. Among the warriors who joined this colossal campaign was Achilles, accompanied by his loyal Myrmidons.

Homer’s account portrays the war as a grinding struggle that stretched over a decade, featuring countless clashes, shifting alliances, divine interventions, and moments of breathtaking heroism. Achilles quickly emerged as one of the Greeks’ most powerful assets—a warrior whose skill and ferocity were unmatched. Yet even he could not prevent the long, bloody deadlock that shaped much of the war’s course.

The Iliad

When The Iliad opens, nine years of brutal fighting have already passed. Achilles has carved out a reputation that borders on myth, and his victories are the backbone of the Greek offensive. Yet, for all his dominance on the battlefield, the poem shifts focus to a different kind of conflict: a bitter dispute between Achilles and Agamemnon, the commanding leader of the Greek forces.

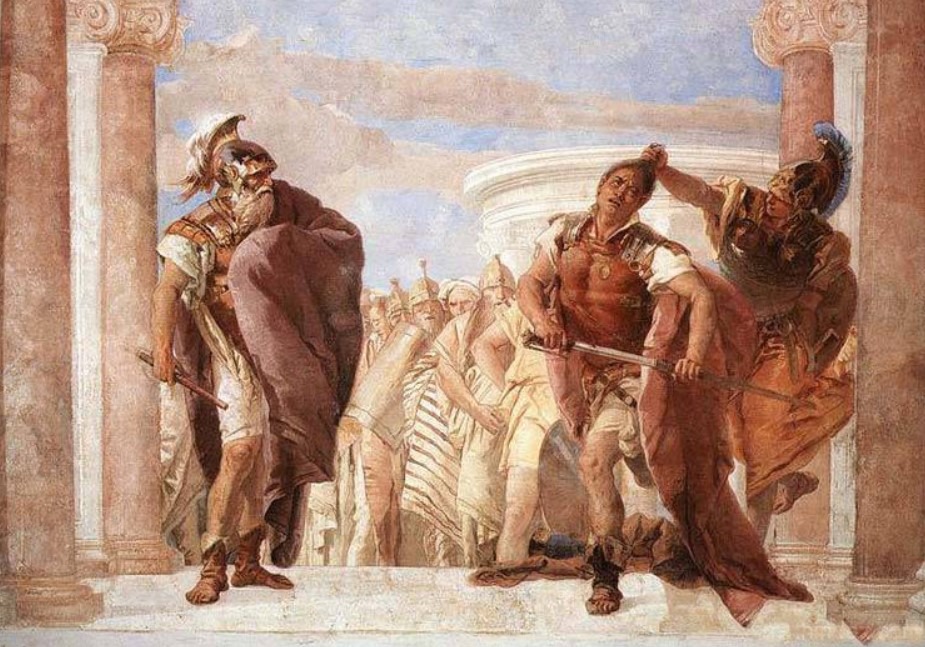

Before the poem’s events, Agamemnon had taken Chryseis, the daughter of a priest of Apollo, as a war prize. When her father attempted to ransom her, Agamemnon refused with arrogance, provoking Apollo to unleash a deadly plague upon the Greek army. To stop the devastation, Agamemnon begrudgingly returned the girl but demanded compensation—specifically Achilles’ own captive bride, Briseis.

Although Achilles obeyed, handing Briseis over, the humiliation cut deep. Feeling dishonored and enraged, he announced that he would no longer fight for Agamemnon. He withdrew to his tent, claiming his armor and refusing to aid the army, a decision that swiftly shifted the balance of power. Without their greatest warrior, the Greeks faltered and the Trojans surged forward with renewed confidence.

Eventually, Patroclus, Achilles’ beloved companion and closest friend, stepped in with a desperate proposal. Achilles would continue his refusal to fight, but Patroclus would wear his armor and lead the Myrmidons into battle. The sight of Achilles’ distinctive armor struck fear into the Trojans, and the plan succeeded—until Apollo intervened once again, guiding Hector to kill Patroclus.

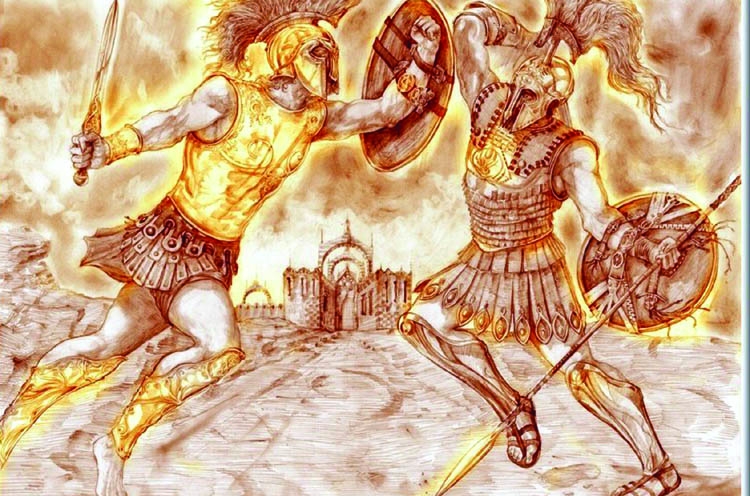

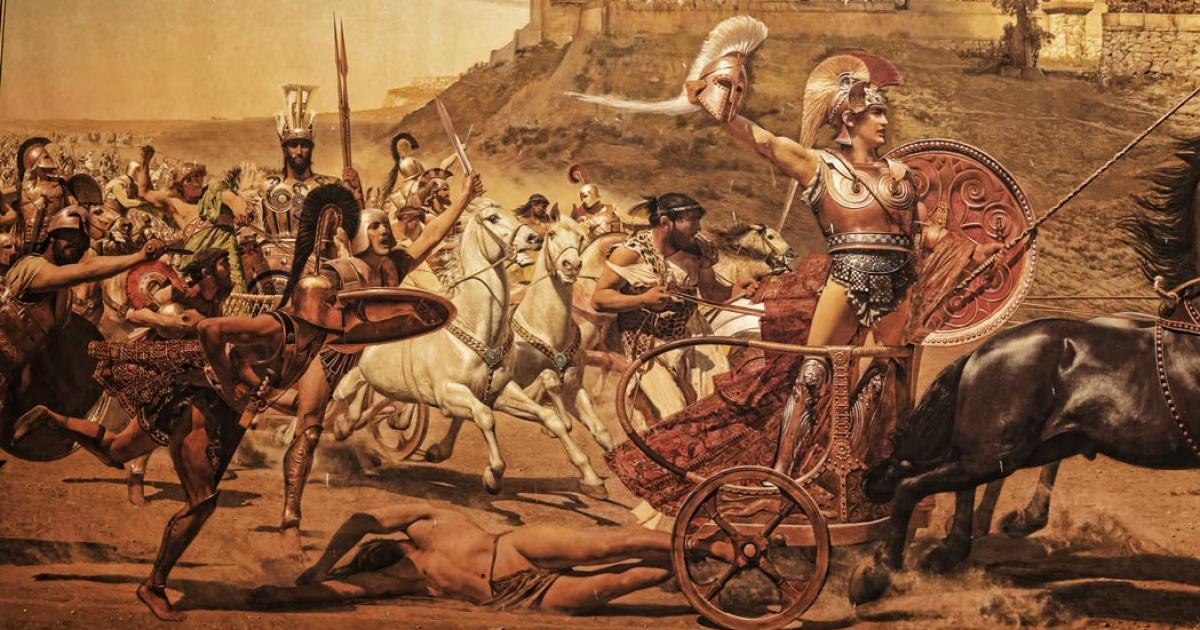

Achilles’ grief was volcanic. Consumed by rage, he reentered the war with a single-minded desire to avenge his friend. His return marked one of the poem’s most intense shifts, as he cut through Trojan lines with devastating fury. Hector, the noble prince of Troy and one of its greatest defenders, eventually faced him near the city walls. Though Hector tried to negotiate, Achilles would not be swayed. He killed him swiftly and then dragged Hector’s lifeless body behind his chariot, denying him the dignity of a proper burial.

Yet even in the depths of anger, Achilles’ humanity surfaced. When King Priam, Hector’s grieving father, came to the Greek camp to plead for his son’s body, Achilles was moved by the old man’s courage and sorrow. He returned Hector’s remains, allowing the Trojans to honor him with the rituals he deserved.

The Fate of Achilles

Homer ends The Iliad before Achilles’ own death, leaving later poets and storytellers to fill in the final chapter of the hero’s life. According to widely accepted traditions, Achilles continued fighting after Hector’s funeral, driven by the need to finish what had begun with Patroclus’ death. But the gods, especially Apollo, had not forgotten the earlier insults and betrayals.

As Achilles entered Troy during a later assault, Paris—known far more for his beauty than his bravery—waited in hiding. Guided by Apollo’s intervention, Paris released an arrow that struck the only vulnerable part of Achilles’ body: the heel where Thetis had grasped him during the Styx ritual. The wound, though small, was fatal. Achilles fell instantly, undefeated in battle yet undone by the one place he could not protect.

His story became one of the most enduring symbols of heroism touched by tragedy. His strength was unmatched, his presence shaped the outcome of an era-defining war, and yet a single overlooked weakness sealed his fate.