Over the course of six years, from 1 September 1939 to 2 September 1945, upwards of 80 million men and women were killed as total war erupted between the Axis and Allied Powers, obliterating much of Europe, Asia and the Pacific, and bankrupting many of the most powerful regimes on Earth.

Characterised by countless massacres, the Holocaust, civilian bombing, famine and nuclear weapons, the war helped shape international legislation that would dictate the future of global politics. It led to the formation of the United Nations but also plunged the US and USSR into a decades-long Cold War.

“At the end of the First World War it had been possible to contemplate going back to business as usual,” Canadian historian and professor Margaret MacMillan wrote in The Guardian in 2009. “However, 1945 was different, so different that it has been called Year Zero.”

She added: “We have long since absorbed and dealt with the physical consequences of the Second World War, but it still remains a very powerful set of memories.”

But how did the Second World War - the most destructive conflict in human history - begin?

Most historians agree that its seeds were sown at the end of the First World War.

In 1918, the “War Guilt Clause” of the Treaty of Versailles held Germany and Austria-Hungary responsible for the entire conflict and imposed on them crippling financial sanctions, territorial dismemberment and isolation.

Germany, for example, was forced to demilitarise the Rhineland and abolish its air force.

Some scholars say that the terms of the treaty were unnecessarily harsh and led to mounting anger in Germany in particular over subsequent decades, but, the BBC says “it would be a mistake to imagine that the Treaty of Versailles was the direct cause of World War 2”.

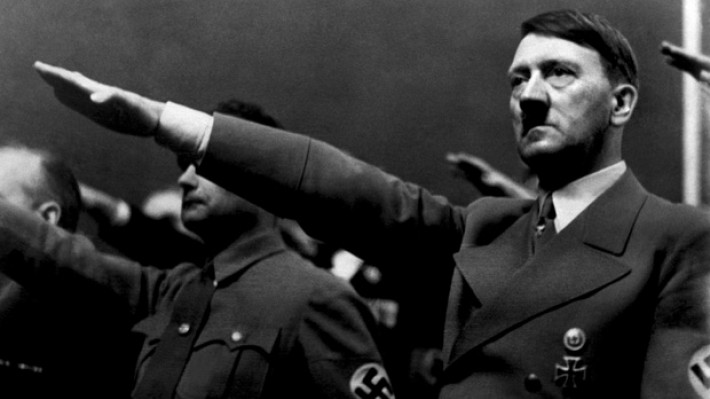

The rise of Hitler

In 2013, Germany marked the 80th anniversary of Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. Angela Merkel presided over the opening of an exhibition in the former SS headquarters in Berlin that charted Hitler’s rise to power. Hitler’s emergence had been made possible, Merkel conceded, because “the majority had, at the very best, behaved with indifference”.

Far from having lifelong military aspirations, Hitler had been a painter in his youth and only joined the Bavarian army at the age of 25 after the outbreak of World War I. He went on to serve primarily as a message runner.

He was decorated twice for bravery, and was injured on two separate occasions – once when he was hit in the thigh by an exploding shell in 1916, and again when he was temporarily blinded by mustard gas towards the end of the war.

The German surrender at the close of the war “left Hitler uprooted and in need of a new focus”, The Daily Telegraph says. He became an intelligence agent in Germany’s much diminished military and was sent to infiltrate the German Workers’ Party. There he found himself inspired by Anton Drexler’s anti-communist, anti-Jewish doctrine and ended up developing his own strain of anti-Semitism.

In September 1919 he announced that the “ultimate goal must definitely be the removal of the Jews altogether”.

Gradually he began to rise through the party ranks, eventually renaming the party the National Socialist German Workers’ Party which adopted the swastika as its emblem.

Hitler won broad public support, attracted large donations and developed a reputation as a potent orator. “He found a willing audience for his views that the Jews were to blame for Germany’s political instability and economic woes,” the Telegraph says.

Throughout the following decade he rose through the ranks to become Germany’s chancellor and, when the president, Paul Von Hindenburg died, Hitler appointed himself Führer – the supreme commander of every Nazi paramilitary organisation in the country.

Hitler denounced the Treaty of Versailles, mounting furious attacks on the unfair terms of the settlement. The treaty incensed Germans, but it had not managed to contain Germany’s potential, and by the mid-1930s the country was surrounded by weak, divided states. “This offered a golden opportunity for Germany to make a second bid for European domination,” the BBC says.

Events of 1939

Throughout the 1930s, several events conspired to push the world back to the brink of war. The Spanish Civil War, the Anschluss (annexation) of Austria, the occupation of the Sudetenland and the subsequent invasion of Czechoslovakia all became key components of the potent tinderbox that was Europe in the late 1930s.

The immediate cause of World War 2 was the German invasion of Poland on 1 September.

The invasion was to become the model for how Germany waged war over the course of the next six years, History says, with a tactic that would become known as the “blitzkrieg” strategy.

“This was characterised by extensive bombing early on to destroy the enemy’s air capacity, railroads, communication lines, and munitions dumps, followed by a massive land invasion with overwhelming numbers of troops, tanks, and artillery. Once the German forces had ploughed their way through, devastating a swath of territory, infantry moved in, picking off any remaining resistance.”

Germany’s vastly superior military technology, coupled with Poland’s catastrophic early strategic miscalculations, meant Hitler was able to claim a swift victory.

The Nazi leader had been confident the invasion would be successful for two important reasons, says the BBC: “First, he was convinced that the deployment of the world’s first armoured corps would swiftly defeat the Polish armed forces... Second, he judged the British and French prime ministers, Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier, to be weak, indecisive leaders who would opt for a peace settlement rather than war.”

Neville Chamberlain has been much derided by many historians for his stance on Nazi Germany, offering, as he did, numerous opportunities for Hitler to honour his commitments and curb his expansionist ambitions. In hindsight, the “appeasement” policy looks absurdly hopeful, but, as William Rees-Mogg argues in The Times “at the time there seemed to be a realistic chance of peace”.

After the invasion of Poland, that chance began to look slimmer and slimmer, and Chamberlain determined that it was no longer possible to stand by while the situation on the continent continued to deteriorate. Britain and France declared war on Germany two days after Germany entered Poland but, slow to mobilise, they provided little in the way of concrete support to their ally, which crumbled in the face of Germany’s lightning war.